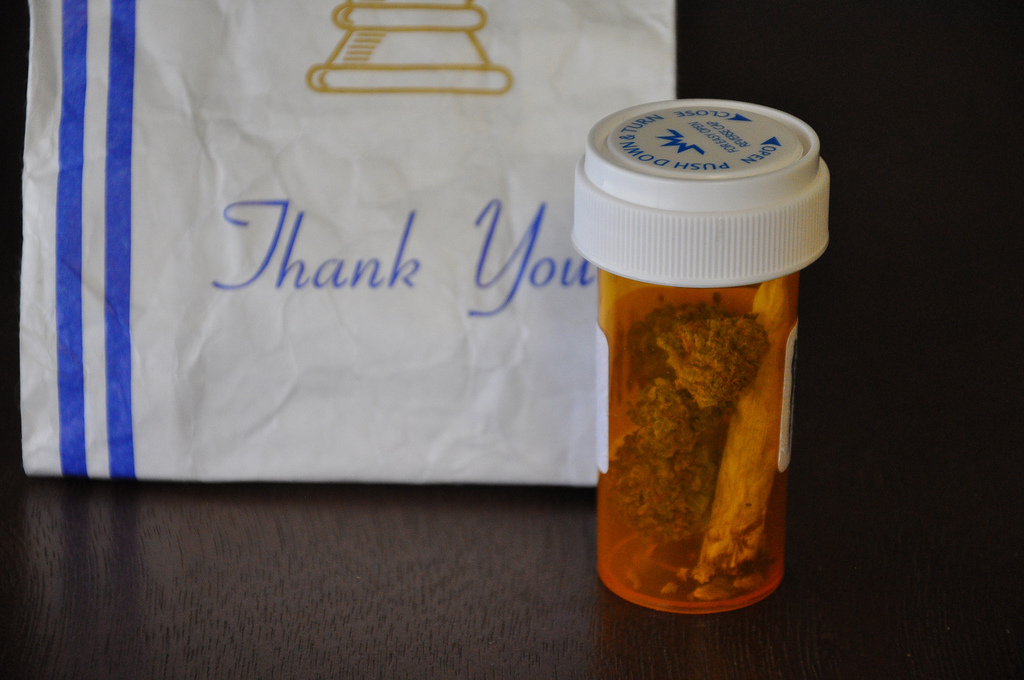

As we move toward the legalization of recreational cannabis, I thought it would be interesting to look at a recent case dealing with medical cannabis and the efforts of one person to get assistance from his province’s workers’ compensation board to contribute to the cost of the medical cannabis prescribed to him.

The case of Skinner v. Nova Scotia (Workers’ Compensation Appeals Tribunal) provides insight into how the use of medical cannabis is sometimes still perceived as an unconventional treatment despite having been legal in Canada for almost two decades, and also how administrative law gives statutory insurance schemes ways to avoid providing benefits to individuals seeking coverage for medically prescribed treatment.

Background

In August, 2010, Gordon Skinner was driving a vehicle owned by his employer, in the course of his job duties. He lost consciousness while driving, left the road and had a collision. He had not returned to work since the accident, and was suffering from chronic pain disorder, anxiety and depression related to the accident.

Mr. Skinner was initially treated with narcotics and anti‑depressants. However, those treatments were not effective for him. In addition, the prolonged use of opiates could have significant side effects for him as a result of a pre‑existing medical condition. His treating psychologist advised that he should use medical cannabis, which he did with much better results for pain management.

Initially, the cost of the medical cannabis was covered by the benefits under Mr. Skinner’s automobile insurance, but those benefits expired after two years. Mr. Skinner then applied to the Nova Scotia Workers’ Compensation Board (WCB), for assistance in covering the expense of medical cannabis. His claim was denied by a case manager and Mr. Skinner appealed the denial to a case hearing officer who denied the appeal. He then appealed to the Workers’ Compensation Appeal Tribunal (WCAT), which denied that appeal in 2016.

Both the WCB and the WCAT (which are both created by Nova Scotia’s Workers’ Compensation Act) relied on a policy passed by the WCB’s board of directors that WCB would provide assistance to injured workers provided that the health care is “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada” in denying benefits to Mr. Skinner. At each level, it was concluded that in Mr. Skinner’s case, medical cannabis was not a treatment that was “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada.”

The WCAT adjudicator came to this conclusion despite finding that the use of medical cannabis was expedient for Mr. Skinner and more effective than more traditional treatments, was a treatment endorsed by medical practitioners, and was a controlled substance that can be used for medicinal purposes. The adjudicator concluded that despite those findings, the use of medical cannabis:

has not yet reached a standard of being a generally accepted medical practice in Canada such that its prescription or use could be considered consistent with Canadian health-care standards. Rather, the evidence demonstrates that there are no Canadian health-care standards in place to govern its therapeutic or medicinal use.

Less than three months later, another case before the WCAT determined that the worker in that case was entitled to coverage for medical cannabis, and as a result, that the use of medical cannabis is a treatment that is “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada.” Two other cases decided by the WCAT in 2017 similarly approved coverage for medical cannabis.

Mr. Skinner appealed his case to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal

By the time Mr. Skinner’s case reached the Court of Appeal, the WCAT had decided in three cases that the use of medical cannabis is a treatment that is “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada” and workers covered under the Nova Scotia’s Workers’ Compensation Act (the Act) are entitled to coverage for medical cannabis. Based on this development, together with the findings of the WCAT as to the fact that medical cannabis was more effective and safer for Mr. Skinner than other treatments, it seems clear that the correct decision for WCAT to have made in Mr. Skinner’s case would have been to provide him coverage for his medical cannabis.

However, the Court denied Mr. Skinner’s appeal. It referred to administrative law doctrines to determine that the decision of WCAT denying benefits to Mr. Skinner did not have to be correct. Instead, if the decision was “reasonable,” the Court of Appeal determined that it could not overturn the decision.

The Court also considered the scheme and purpose of the Act to determine whether the policy that a worker was only entitled to coverage for treatment that was “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada” was consistent with the Act. In that regard, the Court accepted that the WCB was required to maintain the solvency of the Accident Fund established by the Act, and as a result, it was permissible to set policies regarding the treatments for which coverage would and would not be provided.

In considering these two points, it is helpful to consider just what workers’ compensation legislation is ‑- a form of mandatory insurance required by statute. Payments (premiums) are paid by employers into a fund from which benefits are paid to workers who are injured in the course of employment based on the coverage provided by the plan. In fact, in Ontario, the relevant legislation is actually called the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act, 1997 (emphasis added). Looking at the matter from that point of view, it may seem reasonable to expect that the insurer would have to be concerned about its solvency and the ability to pay benefits; and that it would ensure its solvency by a combination of charging the appropriate premiums and having limits or exclusions on what was covered.

However, if a private insurer were to deny a claim for health benefits, the Court would insist that the insurer had correctly applied its policy. The insurer would not be able to avoid providing benefits on the basis of an incorrect interpretation or application of its policy because the Court felt that the insurer’s decision met some standard of reasonableness (even though it was wrong). While it may not have been determinative in Mr. Skinner’s situation, the decision of the Court of Appeal demonstrated that for statutory workers’ compensation schemes, the plan can avoid paying benefits that it should be required to pay because Courts are not willing to interfere with their decisions unless those decisions are not only wrong, but also unreasonable.

Conclusion

In the end, there are two takeaways from this case. First, it is astonishing that in 2012 and 2016, boards entrusted with providing medical benefits for injured workers could determine that the use of medical cannabis was not a treatment that was “consistent with standards of health-care practices in Canada.” Second, and a greater concern on a wider scale, is that when workers’ compensation plans make decisions to deny benefits to injured workers, Courts will not require the plans to make correct decisions, but will instead only intervene where the decisions are unreasonable.

Iler Campbell LLP is a law firm serving co-ops, not-for-profits, charities and socially-minded small business and individuals in Ontario.

Pro Bono provides legal information designed to educate and entertain readers. But legal information is not the same as legal advice — the application of law to an individual’s specific circumstances. While efforts are made to ensure the legal information provided through these columns is useful, we strongly recommend you consult a lawyer for assistance with your particular situation to obtain accurate advice.

Submit requests for future Pro Bono topics to [email protected]. Read past Pro Bono columns here.

Photo: David Trawin/Flickr