You can change the labour conversation. Chip in to rabble’s donation drive today!

Canada’s federal politicians are fond of trumpeting that Canada’s economy has performed better than almost any other jurisdiction, and that we should be thankful for their “prudent economic management.” In actual fact, however, the hard numbers indicate that Canada’s jobs performance has been ho-hum at best — and isn’t getting any better.

Part of the confusion stems from how labour market performance is measured. The government emphasizes absolute growth (or growth rates) in total employment. They boast that Canada has created over a million net new jobs since the worst of the recession: a statement that is correct, but misleading. Remember, any economy with a growing population must create many jobs each year just to keep up with population growth. In Canada’s case, our working-age population grows relatively rapidly: by over 350,000 persons per year (one of the fastest growth rates in the OECD). In other countries (like Germany or Japan), population is stable; hence the labour market can attain a much stronger balance between demand and supply with little or no absolute growth in the total number of jobs. Any increase in absolute employment levels must be considered relative to the supply of available potential workers.

The best way to measure labour market performance, therefore, is to measure employment as a proportion of the working-age population. Economists call this ratio the employment rate. It is also a better performance measure than the official unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is commonly reported in the media, but it is also highly misleading: it excludes individuals who are not working, but are not sufficiently active in their job search to qualify as being truly in the labour market. In Canada’s case, there are almost 400,000 of these “discouraged workers.” Conveniently for the politicians, they disappear from the official unemployment statistics.

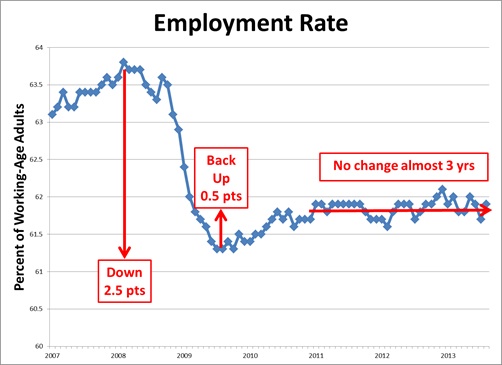

Measured by the employment rate, Canada’s labour market fell off a cliff with the financial crisis and subsequent recession of 2008-09 (see Figure 1). Employment declined by 2.5 percentage points of the working-age population in a matter of months — the fastest fall-off in employment since the 1930s. Luckily, thanks largely to aggressive stimulus efforts in Canada and around the world, that decline was halted by the summer of 2009, and a modest recovery began. For the first 18 months of that recovery, new jobs were created at a decent pace — enough to offset about one-quarter of the damage done in the downturn (rebuilding the employment rate by just over one-half of a percentage point).

Since then, however, there’s been no subsequent sustained progress in recouping the damage done by the recession. Net new job creation has barely kept pace with population growth, and the employment rate has been stagnant for almost three years — languishing far below its pre-recession highs. No wonder it still feels like a recession in the labour market; by this key measure, we are hardly any better off than during the darkest days of the financial crisis. The gradual decline in the official unemployment rate since the end of 2010 has been largely due to declining labour force participation, as discouraged workers exit the formal labour market in droves.

Officially, unemployment is 1.4 million — but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Declining labour force participation corresponds to nearly 400,000 more invisible workers. Other forms of hidden unemployment (including involuntary part-time and other precarious positions) takes the total tally well above 2 million — pushing the true unemployment rate above 12 per cent. The clear constraint facing our labour market is a shortage of jobs (demand), not the availability of willing workers (supply).

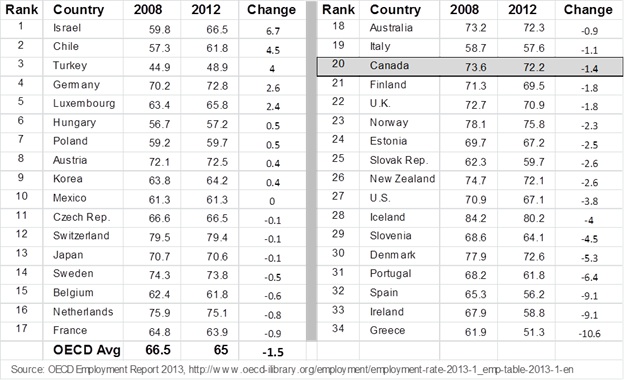

Internationally, too, the weakness of Canada’s performance becomes readily visible when the data is reported correctly. Table 1 reports the cumulative change in the employment rate in 34 different OECD countries, from 2008 (when the recession began) through 2012. Of the 34 countries, Canada ranks 20th (well in the lower half of industrial countries), with net job creation lagging 1.4 points behind population growth. Countries like Turkey, Germany, and Korea have done far better at creating sufficient jobs for their respective populations. Canada has nothing to boast about.

In this context of chronic un- and under-employment, it is jarring that so many employers, business lobbyists, and politicians continue to complain about a supposed shortage of available, willing, and adequately skilled workers. Employers routinely claim they can’t find qualified Canadians to perform even relatively straightforward jobs. They can’t entice Canadians to move from depressed regions, to areas with jobs. They can’t elicit desired levels of effort, discipline and loyalty.

According to this worldview, the biggest challenge facing our labour market is adjusting the attitudes, capabilities and mobility of jobless workers. The question of whether there are any productive, decent jobs for those workers to fill is downplayed or ignored altogether. The problem, in other words, is not with unemployment. The problem is with the unemployed.

For example, within minutes of his appointment last summer as Canada’s new Minister of Employment and Social Development, Jason Kenney took to Twitter to map out his approach. Mr. Kenney tweeted optimistically, “I will work hard to end the paradox of too many people without jobs in an economy that has too many jobs without people.”

That short message spoke volumes about his view of Canada’s labour market. It confirmed that his government will continue to downplay job creation as an economic priority. Instead, Mr. Kenney confirmed he fully accepts the mismatch theory: namely, we must focus on matching up unemployed Canadians with employers anxious to use their services. Help employers find the right workers, in the right place, at the right price, and presto! The problem is solved.

This approach implies that the unavailability of skilled and willing workers is significantly constraining Canada’s recovery. It’s been invoked to support many Conservative policy thrusts, from the scandal-ridden Temporary Foreign Worker Program (which Mr. Kenney oversaw in his last portfolio), to repeated cuts in Employment Insurance eligibility, to the new Canada Jobs Grant initiative which has been roundly criticized by education and labour market experts from coast to coast.

But the mismatch theory is wrong, both theoretically and empirically. Except in very rare circumstances, the labour market almost never runs out of workers. The usual problem is a general and persistent inadequacy of demand for labour on the part of employers. That’s especially obvious today, four years into an economic “recovery” that has left millions of Canadians parked on the economic sidelines.

In fact, OECD evidence confirms that more Canadian workers have post-secondary training (over 50 percent of all workers) than any other industrialized country. Millions of those well-trained Canadians don’t remotely use their existing skills to their full potential. And while public investments in more training always make sense, there is no credible evidence of a general skills shortage in Canada.

From an individual perspective, it is still surely true that it is better to have more education rather than less. But that so-called return to education largely reflects the impact of credentials in improving an individual’s chances of winning the competition for every scarce vacancy. It is what economists call a queuing effect: higher credentials help individuals push their way to the front of the line of job seekers.

From a social cost-benefit perspective, however, this does not imply that education can somehow collectively solve the unemployment problem. Indeed, if every unemployed Canadian got more training, learned to compile a stronger resumé, signed up for LinkedIn, and did all the other things employment counsellors recommend, no new jobs would be created to absorb those ever-more capable job seekers (with the exception, perhaps, of a few resumé-consultants and LinkedIn programmers). Credential inflation and job search skills can help an individual find work, but they cannot fix mass unemployment.

In 2011, Statistics Canada began issuing a monthly report on job vacancies, based on a survey of employers. This is a useful and overdue addition to our labour market database. The most recent data indicate barely 200,000 reported job vacancies in the entire economy. That number has declined (not grown) as our lacklustre recovery stumbled along after 2011. The number of vacancies is very small relative to the overall economy (equivalent to barely one per cent of the labour force).

Moreover, even the best functioning labour market must have a certain stockpile of vacancies at any point in time (simply because it takes time to advertise, receive applications and hire). Employers can even subjectively declare that a position is vacant, when in fact they are just waiting in hopes of recruiting someone to work at a lower wage or salary. Considering the normal time lags in advertising, interviewing and filling positions, the number of jobs truly unfilled because of a genuine lack of qualified applicants is surely less than 100,000.

Even officially, then, there are more than six unemployed Canadians for each job vacancy (1.4 million officially unemployed compared to slightly over 200,000 vacancies). Practically, the ratio is over 20 to 1: true unemployment in excess of two million, compared to under 100,000 unfillable vacancies.

Focusing on job creation should occupy 95 per cent of Mr. Kenney’s attention as Employment Minister. Instead, he will likely focus on social engineering: tough-love efforts to adjust the expectations, attitudes and flexibility of the unemployed, rather than trying to create jobs for them. In this regard, it is not surprising that Mr. Kenney added the term “Social Development” to his portfolio. This further telegraphs his intentions to blame the unemployed, not unemployment, for the continuing weakness in Canada’s labour market.

Stagnation in real wages provides further evidence that there is no generalized constraint on the supply side of the labour market. If skilled workers were genuinely in short supply, their services should be becoming more expensive (as eager employers try to snap up scarce candidates). To the contrary, median hourly wages in Canada have been growing less than one per cent per year since 2010 — lagging far behind inflation.

It’s time to put the so-called skills mismatch in perspective. Yes, Canada should invest heavily in public education and training — not just because it’s important to economic productivity, but because it’s essential to a democratic society. Yes, Canada should dedicate significant resources to job placement and adjustment services, to help willing workers find positions that use their skills and offer meaningful, secure work. On this score, Canada’s actual commitment to active labour market programs pales beside the rhetoric of politicians: according to the OECD Canada spends less on active labour market services than almost any other industrial country. Yes, we could do a better job of matching new graduates with industrial requirements — by emulating, for example, the successful approach of the German apprenticeship system.

But none of this should divert our collective attention from what is by far the most important challenge facing our labour market: stimulating demand and creating new work so that Canadians (more skilled and productive than ever) can support themselves and contribute to our prosperity.

A more appropriate, and hopeful, pledge from an incoming Employment Minister would go something like this: “I will work hard to use every available policy lever to spur job creation, both private and public, so that every willing Canadian can work and support their family.” That’s a pledge that would warm the hearts of our two million unemployed.

Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming!

Jim Stanford is economist for Unifor. This commentary originally appeared in the November 2013 edition of Academic Matters magazine.