On January 6, 2021, photojournalist Saul Loeb was in the U.S. Capitol to cover Congress’ counting of the electoral college votes. He ended up shooting some of the most iconic photographs of the ensuing insurrection.

One photo shows four white men, seated in the Capitol Rotunda. Behind them hangs a massive painting, The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, depicting George Washington’s military victory over the British in 1781. Two of the insurrectionists are looking up, seemingly mesmerized by the massive fresco adorning the Capitol dome.

The fresco, The Apotheosis of Washington, was painted by Constantino Brumidi in 1865. As described on the website of the Architect of the Capitol, it shows “George Washington rising to the heavens in glory.”

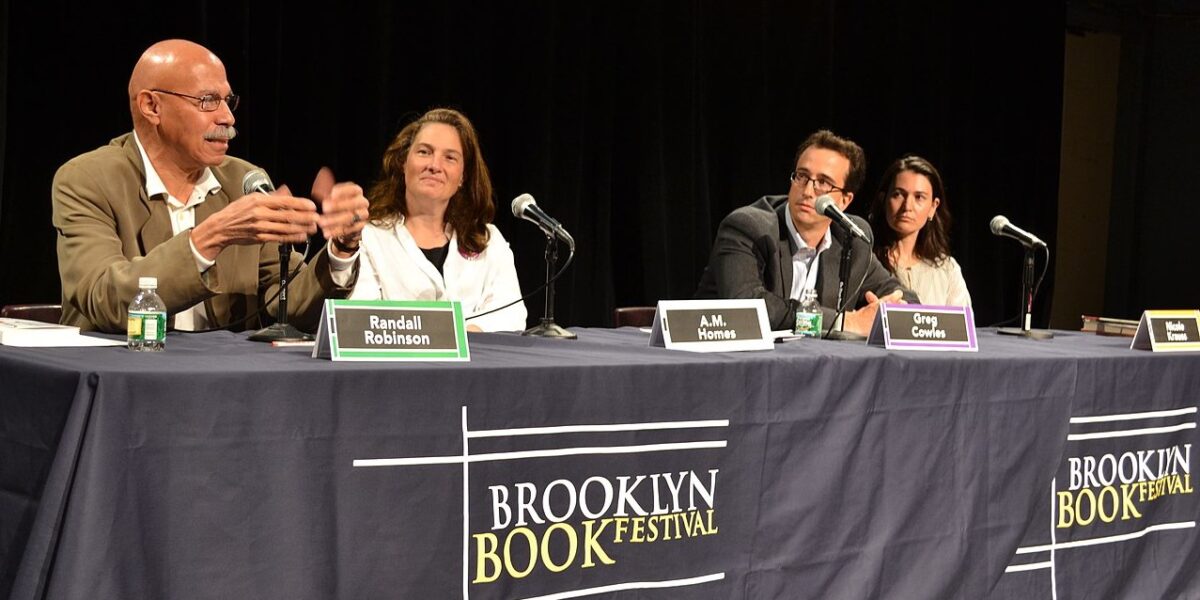

Loeb’s photo brought to mind another insightful viewer of the same work, Randall Robinson, the remarkable African-American author and activist who died this week at the age of 81.

Robinson was born in 1941 in Jim Crow Virginia. After graduating from Harvard Law School, he went to work in Washington, D.C. In 1977, he co-founded TransAfrica to push for a just foreign policy towards Africa and the Caribbean.

Randall Robinson was arrested numerous times in some of the most effective U.S. demonstrations against South-African apartheid. He was also a dedicated champion of the Haitian people, protesting U.S.-supported coups that have decimated Haiti.

Randall Robinson frequently appeared on the Democracy Now! news hour. In 2001, speaking about his book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, he described a realization he had while viewing the Capitol Rotunda fresco:

“George Washington is there surrounded by 60 robed figures. And then there’s a banner unfurled, ‘E pluribus unum’ — ‘Out of many, one’ — but all of the 60 are white…a frieze depicts scenes from American history, describing our development as a nation from the age of discovery to the dawn of aviation. But in these scenes, no Douglass, no Tubman, no Truth, no Blacks at all.”

Robinson continued:

“There are huge paintings set back into…these huge arkose sandstone blocks. These paintings again depict scenes from American history. No Blacks at all…these sandstone blocks had been mined in Stafford County, Virginia by slaves. They were brought up the Potomac River by slaves. They were hauled to the Capitol and put in place by slaves.”

Not long after The Debt was published, Randall Robinson moved with his wife to her native Caribbean island nation of Saint Kitts. He explained:

“I wanted to live in a society for some time, some portion of my life, where race did not have to be a battlement, that one could get beyond that and not feel it always in one’s craw…it used up so much of my energy, and the energy of so many in the United States.”

In 2004, one of us [Amy Goodman] flew in a small chartered plane with Randall Robinson, Congressmember Maxine Waters and several others to the Central African Republic (CAR).

They went to retrieve Haiti’s democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had been forcibly flown there in a U.S. jet following a U.S.-backed coup d’état. They met with CAR’s dictator, François Bozizé, who said he couldn’t release Aristide without U.S. permission.

High-ranking Bush administration officials warned the Aristides against returning to the Western hemisphere. On the return flight to Jamaica with the Aristides, Randall Robinson scoffed, “Whose hemisphere?”

Robinson championed those battered by racism, whether in South Africa, in Haiti, or here at home. His book The Debt remains one of the most compelling arguments for reparations for the descendants of enslaved people. He wrote in the book’s introduction, of the Capitol Rotunda:

“I could not completely place myself outside this spell. Everything about the room was dwarfing — the scale of the art, the size of the round chamber, the height and sheer majesty of the dome. It had combined to achieve the Founding Fathers’ objective, which was, I am certain, to awe. And to hide the building’s and America’s secrets. I thought, then, what a fitting metaphor the Capitol Rotunda was for America’s racial sorrows. In the magnificence of its boast, in the tragedy of its truth, in the effrontery of its deceit. This was the house of Liberty, and it had been built by slaves.”

Most of those insurrectionists who attacked the U.S. Capitol on January 6 embraced Donald Trump’s demand to “Make America Great Again.”

In his searing 2004 memoir, Quitting America : The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land, Randall Robinson wrote, “I have tried to love America but America would not love the ancient, full African whole of me. Thus I could not love America. I had come to know too much of her work.”

For Randall Robinson’s lifelong commitment to racial justice, we remain in his debt.

This column originally appeared in Democracy Now!