People who have worked with me know I am a wannabe archivist, cataloguing the minutia of groups’ social justice work: the meeting minutes, action flyers and posters, postcard campaigns, media releases, news clippings, photographs, and politicians’ correspondence.

I have all that in my home office.

Then there is the red arm band that says ‘Nurse’ worn at a protest in case my services were needed, the plastic handcuffs used on me in another, and more political buttons than you can count.

Thank goodness there are real archivists and archives who value these treasures.

When the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) shut down ten years ago, Professor David Hulchanski, a fellow co-founder of the group, approached the City of Toronto Archives to see if they would accept our materials. These also included overlapping advocacy groups such as the Toronto Coalition Against Homelessness, the TB Action Group, the Coalition Against Police Violence and Housing not War.

Toronto Archives said yes and today the TDRC fonds are well utilized by students and researchers.

Over the summer, I’ve been going through my personal archives at home. In part because I was having too many ‘Groundhog Day’ moments, which I have written about related to homelessness and more recently with respect to nursing. And in part because I’m nostalgic and 50 years of nursing is enough.

Discrimination against the homeless continues

I began with the 1990s. As a young street nurse, it’s no surprise my files include a lot on homelessness and health: the Street Health Report, reduced access to health cards, police inflicted injuries, the resurgence of tuberculosis, homeless deaths and an advocacy response to declare homelessness a social welfare disaster.

Through the 2000s a clearer and more frightening pattern emerges: health and disease outbreaks worsen (TB, SARS, Norwalk virus, Strep A, flu), shelters become exceedingly unhealthy and crowded, extreme heat and cold become persistent threats, clusters of deaths take place, and encampments become routine. These are all markers of a disaster and take place within the political landscape of neoliberalism: cuts to social spending, reliance on charity and cancellation of government funding for social housing.

And the deaths not only continue, they escalate.

I once knew the names of every single person on Toronto’s Homeless Memorial. Front-line workers and I often arranged their funeral or memorial. I remember Tony, whose ashes sat on my work desk awaiting a colleague’s trip to Newfoundland where she would bring him home.

I recently re-watched the still timely documentary Shelter from the Storm which chronicles advocacy for housing through the eyes and actions of TDRC and Tent City residents. I had to write down the names of people in the film that we’ve lost: Brian, Karen, Marty, Nancy, Popeye, Bonnie, Dri and many more.

Today the number of deaths is staggering and no matter the multiple inquest recommendations to prevent further deaths – they are rarely, if ever followed by politicians.

My 12-year-old grandson helped me go through some of my files. Out of curiosity I looked at the Homeless Memorial list again. Since he was born 761 people have died homeless in Toronto. His fresh eyes noted that one year I gave a speech called ‘Never Again’ multiple times. ‘Never Again’ of course referencing that we must never let governments cut funds to social housing, or Medicare, or pensions.

Constant action to create constant pressure

Reading between the lines recounting these tragedies though, my archives tell another story. They disclose a pervasive activism through the decades that created constant pressure on policy makers ranging from polite deputations to direct action. I tell more of those stories in ‘Wielding the Sword. A Campaigner’s Toolkit in the Fight for Social Justice’ in A Knapsack Full of Dreams.

For many years it was accepted, in some cases expected that front line workers, would participate in ‘upstream’ work on the issues affecting their clients downstream. That meant speaking out, organizing, convincing managers to apply for funding. It was often allocated to a half day per week and was called time for health promotion, community development, outreach, research and planning. These names weren’t misnomers. That’s what working on healthy public policy entails.

It wasn’t always smooth. The Conservative Mike Harris government in Ontario created an advocacy chill. Community organizations were audited if they were too vocal in their critique of the government. Many pulled back from allowing their staff to speak out, fearing funding cuts. Rules around what charitable organizations were allowed to do with respect to advocacy were also a deterrent.

I was lucky to have a manager who believed in ‘intentional subversion’, and she understood why I would need to work on calling for an inquest into tuberculosis deaths or advocate for public health action on bedbugs or go to the monthly homeless memorial. The same was true for other organizations, namely Street Health, PARC and Sistering.

Mike Harris is long gone and tax rules around charitable organizations have eased but advocacy chill has again taken a cold grip on agencies. COVID didn’t help.

Worsening homelessness didn’t help. Stigmatizing frontline workers as ‘advocates’ didn’t help.

Still missing a national housing program

The successes we have seen over the last twenty years have only come from activism, from the experiences of front-line workers and unhoused people taking politicians to task, making bureaucrats accountable. The successes came with the labour movement by our side, with seniors, students and more.

Successes such as: the federal homelessness program (with its various acronyms SCPI, HPI), the opening of emergency shelters, the use of federal armouries and empty hospitals for shelter, harm reduction programs, palliative care programs, pilot rent supplement programs, warming and cooling centres. These are to be celebrated.

Missing in this list is housing. Yes, we have a national housing ‘strategy’, but I don’t see it here in Toronto. Across the country we don’t see it.

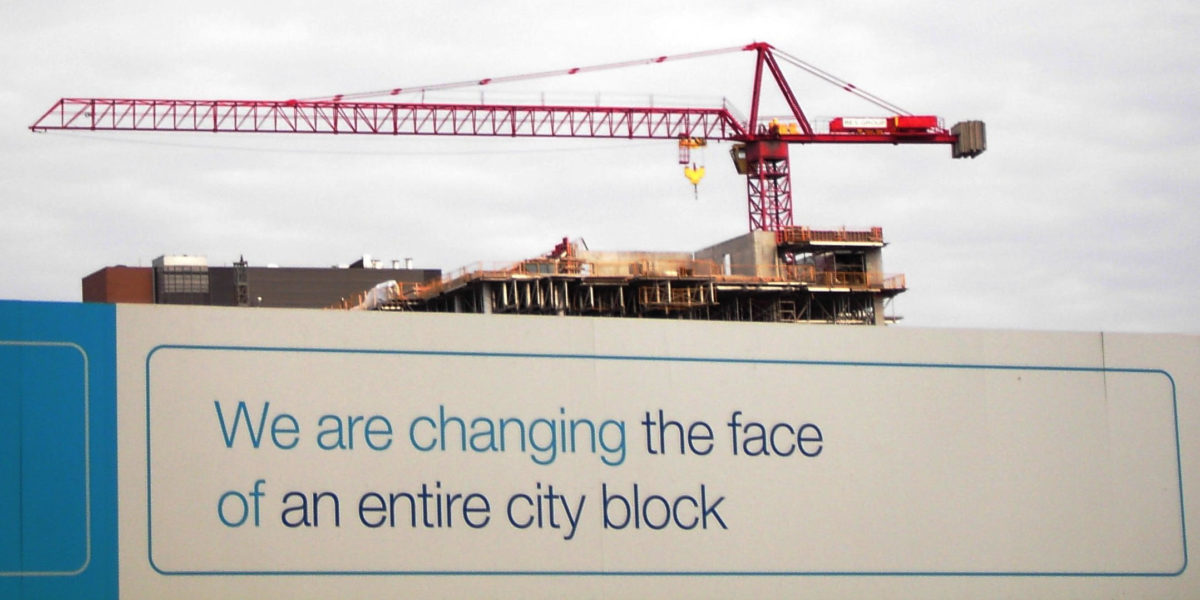

We see the financialization of housing, condominiums stretching into the sky and band aid measures such as inclusionary zoning and allowing secondary suites in homes.

My long-time colleague Beric German sums up what must be our work:

“We fight for shelters because people face disaster. We know that ultimately a number of other national housing programs have to be implemented. That means that we need housing, public housing, social housing, that is available to us all. This will not be dealt with in the private sector. In the condominium sector.”

November 22 is coming. It’s National Housing Day. It needs to be an activist day to fight for Housing For All. My archives tell the painful story of what happens without housing for all, but it also tells us we can make a difference.