Quaint as it now seems, not long ago this was considered a good basic plan: Work hard all your life and then retire with a comfortable pension.

In recent times, a new plan has replaced it: Work hard all your life and then all bets are off.

The notion of retirement security in exchange for a lifetime of hard work — a central element in the implicit social contract between capital and labour in the postwar years — has been effectively tossed aside, as corporations have become more insatiable in their demands and governments have increasingly abandoned workers.

Stephen Harper’s government hiked the eligibility age for Old Age Security benefits to 67, effectively depriving all future Canadian retirees of two years of basic retirement income.

And it has steadfastly refused to strengthen the Canada Pension Plan, leaving retired Canadians with an average income of $18,000 a year in public pension benefits — far less than what a full-time minimum-wage earner makes in Ontario.

And now, the Harper government is engaging in a fresh frontal assault on the retirement incomes of beleagured Canadian workers.

In what amounts to a radical overhaul, it announced last April that it intends to change long-standing legislation governing workplace pensions in ways that would allow employers (private sector and Crown corporations) to walk away from pension commitments they made to employees, even after those employees have paid into the plans throughout their working years.

None of this has received much attention, although it could affect hundreds of thousands of workers.

Income security for retired workers was one of the key benefits won by unions in the postwar era, allowing ordinary Canadians to plan their lives to ensure they wouldn’t end up homeless, or sharing what their pets eat.

Workplace pensions were always expected to be a key part of that retirement security. Unlike many European countries, where public pensions were generous enough to serve as the centerpiece of a retiree’s income, the Canadian government kept public pension benefits low and encouraged workers to rely on workplace pensions.

That worked fine for those who were able to negotiate workplace pensions with an employer — generally those who had a union to represent them. In such cases, both the employer and the employees typically contributed to the plan, under terms that specified what benefits would be paid out to employees in their retirement.

Employers now want to be able to fundamentally rewrite the terms of those workplace pension deals so that, if the market plunges and the pension fund declines, the pay-outs will be less — in effect, shifting the risk from the company to the retiree.

When it comes to new hires, many employers now offer only the new-style pensions. But the legislation proposed by Harper would create a way for employers to open up existing pension deals — effectively changing the rules in mid-stream, after workers have spent years paying into their plans.

There have been few objections from media commentators, who have ignored the change or treated it as simply a fait accompli, part of a new economic reality.

It’s not a fait accompli, in fact. It involves the government changing laws, overturning legislation that was put in place to protect working people in an era when unions and workers had some political clout.

There’s no evidence that the change is necessary for economic reasons, or to ensure the viability of corporations.

While the ongoing recession has left the workforce shaken and insecure, corporate Canada has made a stunning recovery since 2008. Profits are up dramatically, and Canadian corporations are now sitting on a stunning $630 billion in cash holdings — which they are declining to invest.

None of this fabulous wealth is being shared with workers, who increasingly are expected to fend for themselves.

Perhaps this is simply part of a new mentality — of boldly embracing risk — that is integral to the global economy.

It’s striking, however, that a bold embrace of risk is only expected of those in the lower echelons of the corporate world. At the top, executives cling to old-world notions — like securing comfortable retirements.

The Royal Bank, the country’s largest bank, switched over to the new-style pension system in 2011, so that all new employees will be obliged to face a risky pension future.

RBC CEO Gordon Nixon didn’t see the need to modify his own pension deal, however. When he retires later this week at the age of 57, he’ll receive a pension of $1.68 million a year, which will rise to an even more comfortable $2 million a year when he turns 65.

And he’ll be able to count on that stipend — which works out to more than $5,000 a day — for the rest of his life.

Risk may be good for those lower down the ladder but, for those at the top, guaranteed lifetime abundance apparently still has its place in the global economy.

Winner of a National Newspaper Award, Linda McQuaig has been a reporter for the Globe and Mail, a columnist for the National Post and the Toronto Star. She was the New Democrat candidate in Toronto Centre in 2013. She is the author of seven controversial best-sellers, including Shooting the Hippo: Death by Deficit and other Canadian Myths and It’s the Crude, Dude: War, Big Oil and the Fight for the Planet. Her most recent book (co-written with Neil Brooks) is The Trouble with Billionaires: How the Super-Rich Hijacked the World, and How We Can Take It Back.

This article is reprinted with permission from iPolitics ![]()

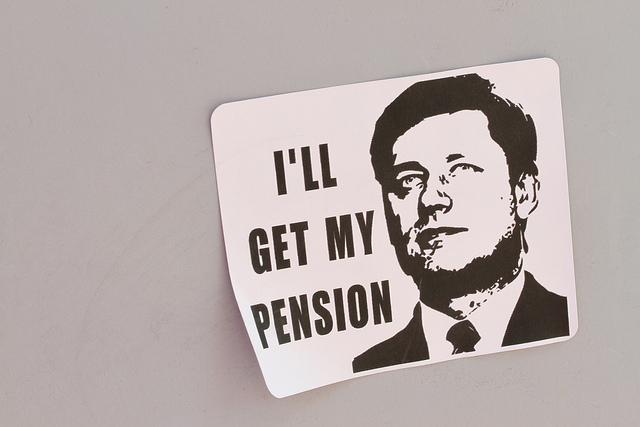

Photo: Danielle Scott/flickr