On Wednesday, we introduced a roundtable with four Indigenous family and community members who are leading the calls for justice for Indigenous women, girls, two-spirit, and trans people. Bridget Tolley, Zhaawanongnoodin (Colleen Cardinal), Carol Martin and Audrey Huntley continue the conversation today on what they envision as meaningful, community-led solutions to the ongoing reality of gendered colonial violence. As renowned Indigenous feminist Lee Maracle writes, “It is not simply about ‘ending violence,’ the violation is the colonial order.”

You can read the introduction and Part 1 of the roundtable here.

There have been increasing calls for a national inquiry, as well as accompanying dialogue about the usefulness of a national inquiry whose terms are set by the state. Dr. Sarah Hunt of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation, for example, has written, “While the government’s refusal to hold an inquiry clearly demonstrates its inability to take our lives and our deaths seriously, this is not necessarily the route to real change.” You have spent years advocating for a national inquiry but have also expressed its limitations. Can you talk more about this?

Audrey: It depends on who is calling for a national inquiry. With some allies who we had been asking to support this demand years ago, frankly it annoys me that it took so long. Also mainstream calls from political parties did not come until a time when we, basically frustrated with the sham provincial inquiry in B.C., were no longer even making the demand.

I think the increasing calls from within our community for an inquiry arise from a need for the severity of the violence to be recognized. People are in a lot of pain and an inquiry would counter the trauma of societal indifference that compounds family members’ grief. That being said, we know that the state has no interest in ending the violence. In fact, it is in the state’s interest that we disappear. Ultimately, I don’t think a politics of recognition will lead to deep change. I prefer to keep building community capacity on the ground and to work to foster the resurgence of cultural traditions and connectedness to the land.

It’s unfortunate that the question of an inquiry gets framed by media as if it’s the end and be all, or it’s that and nothing else. We know the root causes already and there are plenty of recommendations from previous studies that have yet to be implemented. And we should still have an inquiry and it should be led by family members and involve getting their demands for answers on unsolved cases met, reopening cases, sharing police files etc. And that should not exclude immediate action on providing access to safe housing, education and employment, and more shelters to reduce the extreme poverty and vulnerability faced by many Indigenous women.

Bridget: You cannot leave those who created the problem in charge of the solution. We already have over 50 reports and 700 recommendations and very few have been implemented. Even the B.C. provincial missing women’s inquiry had 63 recommendations and they only implemented three of those recommendations. How many more reports and roundtables do we need? We need action and we need to actually implement the recommendations. I do think a public inquiry might help, but only if it will lead to something concrete for our women. But if we are going to spend millions of dollars on a national public inquiry and then say, “oh we have no money,” then spend the money to actually do something.

The families are begging Native Women’s Association of Canada and Assembly of First Nations for help, but they don’t help us. Now they are calling for a public inquiry but it’s hard to have any trust in these organizations or the government. I think of those marching for a quarter century in the West — that’s a good three generations! I am 55 years old and I would like to see some change before I die. But I don’t know if that change will come from a public inquiry. I think we need to give the family members more voice and let them speak for themselves. Every family has a different story and only they can tell their own story. When family members have a chance to talk and to meet each other and feel one another’s support — that is how we heal.

Colleen: I can see the urgency and desperation in the call for the inquiry — families want answers — but I believe it will not stop the murders or disappearances of Indigenous women, two-spirit, and trans people. Asking the state to investigate itself is futile. The state will never admit they were racist in the making of Canada. In fact, Canada still hides the truth of how this country is financed through the manipulation of the treaty-making process in order to access Indigenous land and resources.

A proper inquiry would reveal that police forces are killing and assaulting Indigenous women, as indicated in a recent Human Rights Watch report. A national inquiry may lead to the Canadian state being held accountable in International Criminal Court for the genocide of Indigenous people in Canada. But the government doesn’t care; it is already faced with reports, research, testimony, recommendations, tribunals and evidence. I also question how an inquiry would be enacted: who will oversee it, who are they accountable to, how much money would be set aside, and who stands to benefit financially from an inquiry? Will families of missing and murdered women be involved?

Carol: The provincial missing women’s inquiry was a stage performance. They did not recognize our presence, never mind our voices. We held no position within their judicial system and we were not recognized as human beings capable of standing up to the injustice that took place — and still takes place — within their courtrooms. This reflects racism but still we are supposed to believe in this judicial system! Racism is conditioned, taught, and projected in society; it is a learned behaviour towards Indigenous women and girls where we are not valued as much as a non-Native person. Being Indigenous is the first strike against us, and then being a woman is a second strike. Living in poverty is another strike, and being an addict, etc. The more labels we have against us, the more strikes we have put against us.

Responses from successive governments have been policing and surveillance measures, for example increased policing budgets, more policing coordination, DNA databases etc. There is a consistent tension around the role of police in addressing racialized and/or colonial gender violence: advocating long-term abolition of police and prisons, but also sometimes the call for more appropriate police involvement in specific situations. What are your thoughts on this?

Bridget: In most of our cases the police are the problem. Like in my case, I am accusing the police directly of killing my mother and the police have not even spoken to me. They are hiding and covering up their mistakes. So how are we supposed to have any trust in the police? The government are our abusers and the government hires the police, so obviously we aren’t going to get any solutions from our own abusers. The police and government are just worried about increasing their own budgets. I am so tired of saying this in all the meetings with all the leaders and the chiefs: the police can’t help us find a solution and this is why nothing is getting better.

Colleen: The state responding to violence against Indigenous women by ramping up police presence and building more jails perpetuates the cycle of violence. The RCMP already has been identified as being perpetrators of violence towards Indigenous women. Prisons are institutionalizing Indigenous people and have become the new residential school system. The government is going to war on Indigenous people using the police as their enforcers to serve and protect their oil, land, and resource assets. I have only had bad experiences with the police when I need protection. I would hold out on calling the police for help because I feel I am more likely to be subject to racial profiling, assault, or being criminalized or shot by them than being helped.

Carol: I have a lack of belief in the law, justice institutions, and police system here in this occupied land. Some people believe it is a great system but I think that the system has been corrupted by racism and classism. Unlike upper-class people, Indigenous people have a lot of difficulty believing there is fairness before the law. The police are literally a gun in the establishment’s hand and racism is used as a weapon by the wealthy to increase their profits.

Audrey: I come from abolitionist organizing. No More Silence has been well positioned to express a fundamental critique of policing institutions and state complicity in violence as we are not dependent on state funding. I do see, however, that folks working in Aboriginal agencies assist people in surviving the brutalization of the system every day and may be in more direct contact with police than we have to be.

If police involvement in anti-violence work actually led to less police brutalization of vulnerable people by the police I would be all for it, but I don’t see that happening in Toronto or anywhere. Most recently, headlines romanticized an officer’s abduction of an intoxicated woman from jail to rape her in private. Even judges have taken advantage of their positions of power to victimize Indigenous women and girls, and we see women dying in custody. In Toronto we go to police headquarters because a focus of our work has been to talk about impunity and the complicity of state institutions. We don’t go there expecting them to change but rather in defiance and to assert our sovereignty in the face of their complicity.

The tension expresses itself most painfully, I think, in the dilemma of families with unanswered questions who want to know what happened to their loved ones. It is horrific to be dependent — while in a place of shock and grief — on an institution for answers that is hostile to your community and to you, and indifferent to the death of your loved one. It gets messy when people’s hope for justice is equated with police action and colonizer sentencing. Again I look to strengthening community relationships and creating safe places where we can foster the resurgence of our cultural traditions. Hopefully that way we influence society as a whole and make it unacceptable to discount the lives of Indigenous women and girls.

Are there additional or alternative community-based solutions to state-based inquiries and policing initiatives that you envision or see in practice?

Colleen: I believe in community-based work. One movement that I became a part of and support wholeheartedly is #ItStartsWithUs, a community-led grassroots initiative led by No More Silence – Toronto, Native Youth Sexual Health Network and Families of Sisters in Spirit. It has a tribute section for the missing and murdered Indigenous women with the words of families and loved ones, along with pictures and stories. It is important because all we see are police or media reports that are often poorly written, inaccurate or misleading.

I have found great empowerment from building community with Indigenous people and non-Indigenous settlers who are committed to understanding, listening and supporting. Not only is it important for settlers to understand how they are implicated in colonization on Indigenous land, but to also challenge mainstream media to do better when reporting about Indigenous women’s deaths or disappearances, and to really understand that the women who have been murdered or gone missing meant the world to their loved ones and communities.

We also really need to do the work within ourselves to unlearn harmful attitudes like victim-blaming, slut-shaming, rape culture and homophobia. We should also challenge those around us in our families, schools, and workplaces.

Carol: We must look at ourselves and learn from that and from each other. We all know racism is a projection of our fears onto another person and we must treat this disease of our society. We must understand it and acknowledge that it does exist; we can’t hide it or camouflage it. The institutions in this country have been built on racism since the residential schools. And the racism of those institutions was internalized by individuals who were set up to become self-destructive. We must put more emphasis on the idea that it’s all right to be different. We must understand that racism — and all the “isms” — grows from a hostility against those of another tribe, race, religion, nationality, or class in our society.

Bridget: We, ourselves, have to break the cycle of violence. Within our families, we have to believe someone when they disclose something. The impacts of residential school have been severe and we are brought up to learn all the wrong things. But that is not the way. We have to teach our children to respect and love their mother and sister. We cannot expect that love and respect from colonial society, so we have to do it ourselves. Because we have been deliberately deprived of love, showing love is so important.

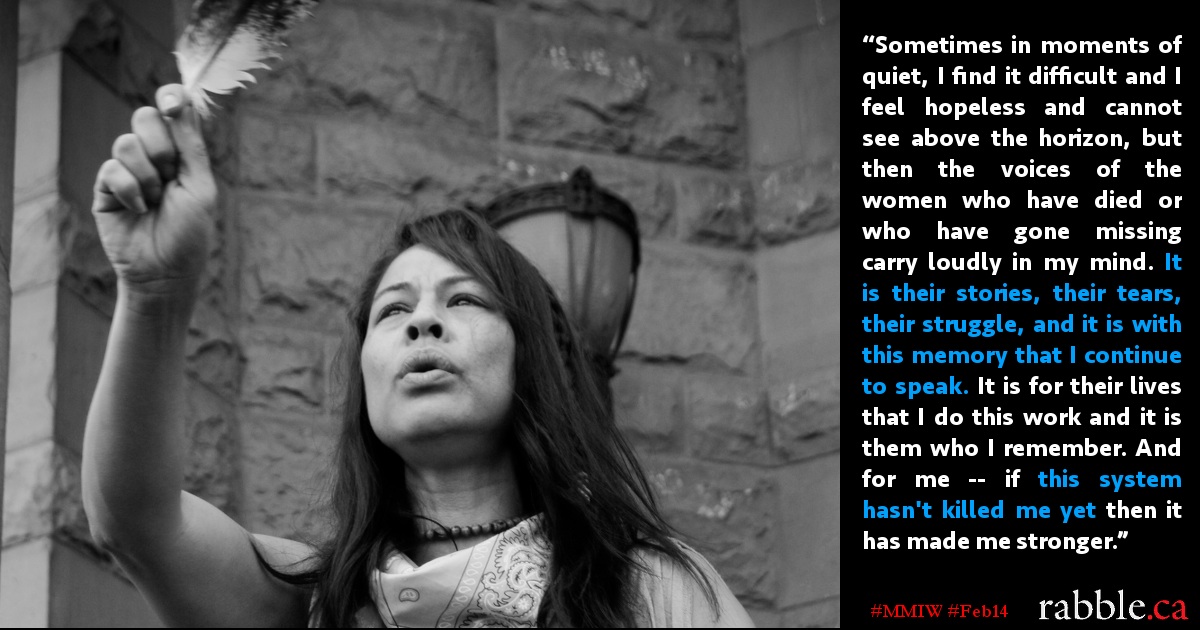

Audrey: I look primarily to community-based solutions. For me, that means the #ItStartsWithUs project, which is a community-led database. It also means inter-generational relationship building, connecting with allies who understand that we work for decolonization, and practicing those teachings of love, kindness, humility, respect and re/connecting with the land.

What do you feel is the most pressing message or call to action with respect to justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls that is not being heard enough and needs to be amplified?

Carol: We need to get to the roots of violence against Indigenous women and girls. This means exploring the ongoing systemic racism, genocide and violence against Indigenous women and girls. This “great and rich” country has taken many lives, and it is a legacy that Canadians can no longer ignore. Indigenous warriors will continue to bring forward our voices because we know how terribly wrong this system is. The weight of racism crushes my spirit. I also hear the silent screams of the many missing and murdered women who are screaming for justice. We are waiting for you to wake up to this reality that is a horror story with no ending.

Ask yourself: how could this violence continue with no intervention? You have to un-think the way society wants you think. Instead, question what you see and hear, and you will then understand what racism is and what it does to us. The daily challenges of racism tear us down and make us more vulnerable, which puts us at a much greater risk of violence and death. And the minute you understand how deep the roots of racism are, you are responsible to do something to change it. The future lies in your hand, in your voice, in your action to make those changes.

Audrey: We need to centre the voices of those who are most vulnerable and experience the highest rates of violence: sex workers, trans and two-spirit peoples. I am not surprised that, despite knowing it will be struck down as unconstitutional, the Harper government would pass Bill C-36 just to pander to their most conservative electorate. Many women will be murdered through the enforcement of this legislation.

We should be standing with sex workers organizing against this bill and calling for an end to criminalization. It is really hard to see Indigenous women choosing to align themselves with such a reactionary government in their whorephobia. Sometimes they are not only shaming and stigmatizing sex workers, but also contributing to criminalization and loss of employment. This is also violence and should be called out. We should not tolerate the invibilizing of Indigenous women choosing to work as sex workers. I am working for decolonization and I think that includes decolonizing internalized colonizer thinking around sexuality and gender. It should include respect for those most affected, who are best situated to address their issues.

I have learned a lot from women and trans people in the trade who have pointed out that criminalization of sex work also hurts Indigenous people who are not in the sex trade. More surveillance and policing means more profiling, harassment, arrests and police violence towards all Indigenous women (especially trans and two-spirited women) who are stereotyped as sex workers as well as towards Indigenous men who live in the poor and working-class neighbourhoods that sex work strolls have been pushed into. The abolitionists don’t mention that the enforcement is always in racialized, poor/working-class neighbourhoods like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Why would we support increasing the burden of policing on all Indigenous people when we have solutions to the violence facing Indigenous sex workers (like housing, jobs, addiction services)?

Bridget: People need to listen to the families. We are calling for support and I do not know how much clearer we need to make it that we need help when our loved ones go missing. So people need to listen to the families when we say, “support the grassroots.”

Colleen: The most pressing message is that it starts with us. Start looking at what we can do now; stop looking to the state to save us.

Harsha Walia (@HarshaWalia) is a South Asian activist and writer based in Vancouver, unceded Coast Salish Territories. She has been a member of the February 14 Women’s Memorial March Committee since 2006 and also been involved in grassroots migrant justice, feminist, anti-racist, Indigenous solidarity, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist movements for over a decade.