Douglas Cardinal, architect of the Canadian Museum of Civilization and other well-known buildings, spoke on The Vision for the National Historic Site at the Sacred Chaudière Falls at the Peoples’ Social Forum, Thursday, August 21 in Ottawa.

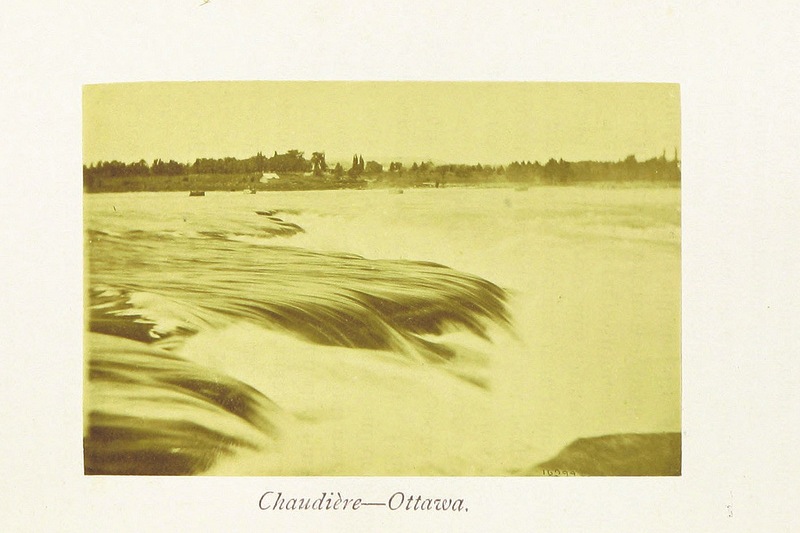

The Chaudière Falls were considered sacred by speakers of Algonquin languages, living throughout North America from the Atlantic to the Rockies. Some made long pilgrimages and honoured the area with prayer and tobacco ceremonies. The circular rapids below the falls were seen as a place where the wheel of life spins, symbolized by the bowl of the sacred pipe. They emitted a distinct sound heard for miles around.

The Chaudière Falls also formerly hosted huge numbers of American eels, which had a remarkable ability to scale the slippery rocks and continue up the Ottawa River. A few young eels still make the 4,500-kilometre migration from their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea; even fewer adult eels make the return journey (many are chopped to bits in hydro turbines).

The American eel meant to Algonquin peoples what salmon meant to Indigenous peoples living on the Pacific coast — an important food resource, and also a powerful symbol of the endless cycle of nature. According to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, “Historically, the Ottawa River habitat would have potentially contributed 255,000 female silver eels annually.” Today, “the Ottawa River is blocked by 12 hydro-dams, none of which is equipped with an eel ladder.”

Mr. Cardinal spoke of the legacy of Grandfather William Commanda, an Algonquin elder who passed away in 2011 at the age of 97. Grandfather Commanda carried three sacred wampum belts — the Ancient Seven Fires Prophecy Belt, which dates from prehistoric times; the Welcoming and Sharing Three Figure Wampum Belt from the 1700s, which calls for friendship between Indigenous Peoples and European immigrants; and the Jay Treaty Border Crossing Belt of 1896, which affirms territorial connections between Canada and the United States. He tirelessly advanced the concept of the Circle of All Nations as a vision of peace among all peoples.

Grandfather Commanda had asked Mr. Cardinal to prepare architectural designs for an Aboriginal history centre, a peace centre and a conference facility at the Chaudière Falls area. Mr. Cardinal presented these at the Peoples’ Social Forum. Grandfather Commanda also advocated removal of the dam and hydropower facilities at the site and “freeing of the magnificent sacred circular falls.”

Mr. Cardinal noted during his talk that property rights in the Chaudière Falls area (including Chaudiere and Victoria Islands just downstream from the Falls) are unclear. According to the Asinabka website, when Grandfather Commanda asked the National Capital Commission (NCC) to prove its legal right to the area, NCC lawyers were unable to produce documentation. The federal government had been leasing Chaudière Island in perpetuity to Domtar, a forest products company, for approximately $100 a year, based on an arrangement developed after Algonquin peoples were driven from the area in 1856.

Decades of use for pulp and paper manufacturing have left the Domtar lands contaminated with acids, sulfur compounds, mercury, lead and petroleum compounds, according to a recent Ottawa Citizen article. The article quotes a spokesman for Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird (responsible for the NCC) as saying that the federal government “will remain actively interested and involved in any environmental cleanup and development of this site,” and “the minister is excited about development proposals.”

The NCC seems confused about development priorities for the Chaudière Falls area. An NCC report based on a national consultation exercise (Horizon 2067: The Plan for Canada’s Capital) states that “the area around Victoria Island should be developed as a dense urban development similar to Vancouver’s Granville Island or Toronto’s Distillery District.” But the report also notes that at the September 2011 Aboriginal Peoples Dialogue that launched this public consultation, “Victoria Island came up in the context of honouring William Commanda’s vision for a Circle of All Nations.”

The NCC document adds, “It was mentioned that a place of healing and reconciliation is the anchor to an Aboriginal vision for the Capital and should be built on Victoria Island. This gathering place would be sacred. Diplomats and embassies should be involved in this process in order to establish a gathering place where Aboriginal peoples around the world could visit. This place of belonging would be a great source of pride for the Capital and Aboriginal communities and youth.”

A showdown between these competing visions — sacred site or urban development — is looming. In July 2013, Ottawa-based Windmill Development Group signed a letter of intent to purchase the Domtar site on the Chaudière Islands. The Windmill website says, “Our vision for the Chaudière Islands is to reinvent a historically rich, industrial space into a vibrant, world-class, sustainable, pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use development.”

In May 2014 the City of Ottawa posted details on its development website of Windmill’s application to change the zoning of the Chaudière Islands from open space to mixed use. The NCC is now holding regular meetings to discuss Windmill’s plans, which include a 15-story condo tower.

Mr. Cardinal was reluctant to speculate on whether these differing worldviews can be reconciled. He recalled that Algonquin-speaking peoples were largely hunters and gatherers, and hence less warlike than peoples (e.g., Europeans) who defended lands they had cleared for agriculture. When his Blackfoot ancestors did battle on the Great Plains, they demonstrated courage by approaching an enemy warrior unarmed and striking him with a coup-stick. Mr. Cardinal noted that a Canadian War Museum has already been built on the Chaudière Falls site, but Canada lacks a centre for peace.

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

Image: The British Library/flickr