The tar sands may seem like a universe away to anyone who doesn’t live in Alberta or work in the oil industry, and this desire to get intimate with the issue and the people connected to it is what drove Am Johal and Matt Hern to attempt a different investigation.

Johal, who works at Simon Fraser University’s Vancity Office of Community Engagement, and Hern, an activist and writer based in Vancouver, managed to also corral Joe Sacco, the eminent comic book artist known for such acclaimed graphic novels as Palestine, Safe Area Goražde and The Fixer.

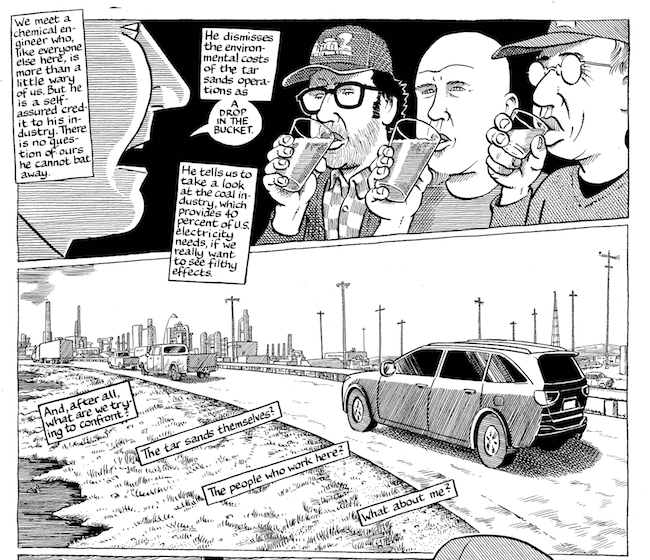

The trio have published a mixed style of investigative reportage in Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life: A Tar Sands Tale (MIT Press) that combines a road trip with political analysis, investigative reporting and in-depth interviews to provide a 360-degree view of the tar sands.

rabble.ca’s June Chua caught up with Johal to unpack the objectives and the stories behind the book’s journey.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

June Chua: Joe Sacco is an internationally recognized comic book artist and journalist, he’s gone to war zones and many areas of conflict, how did he get involved?

Am Johal: I work at Simon Fraser University at the School for Contemporary Arts and part of my role is to invite speakers and I’ve been a fan of Joe for a long time, so he got invited to come and speak. We became friends.

Matt is also a friend of mine and he was writing this book called “What is a city for?” about the displacement of African-Americans in Portland due to gentrification. Joe is living in Portland, so I got them together. Then, we also found out Joe was working on a book set in the Northwest Territories, it will be out next fall and it’s partially about the relationship between Indigenous people and development. Matt came up with the idea for this book and we all got roped into it!

JC: The book is structured as a trip which starts in Vancouver, goes to Edmonton and then Fort McMurray, and after, the Little Buffalo and Janvier Indigenous communities. What’s the reasoning behind this?

AJ: We wanted to play with the form of the traditional academic book, so we did it in the form of a road trip and it was a way to make the theory more accessible.

Also, for us in Vancouver — where Greenpeace started, where there’s a lot of opposition from Indigenous and environmental groups to the pipeline — it is easy for us to critique the tar sands from far away. It made sense to begin where we were and to head off towards Alberta to see it up close

We all have preconceived ideas about the oil industry and we had seen a number of media stories. It’s very easy to go there and do “enviro-porn” and show the extent of the damage and to think of the people working there as “knuckle-dragging” individuals. We weren’t interested in that view. We genuinely wanted to meet people there. There are all sorts of people involved in the tar sands that don’t live there and that includes bankers in Toronto and other companies located elsewhere.

Matt had a daughter who decided to go to Fort Mac for nursing school and this made economic sense for her, so it made him think about real life and everyday people.

JC: So, you get to Alberta and what do you encounter?

AJ: Edmonton is a very interesting city. it’s the capital. And when you get there you realize just how intertwined the province is with the oil industry — the NHL team is the Edmonton Oilers and their junior team are the Oil Kings. If you are from there, it’s all quite banal and normal. We got to see how government and capital come together and how Alberta is so economically and culturally built around oil.

Then three days later, we arrived in Fort McMurray and it was the day Rachel Notley was elected. We had planned this trip far in advance, so it was a good coincidence. You can see how prairie populism is different from other places. The NDP in Alberta is more about right populism because in Alberta, whether you are leftwing or rightwing, it’s impossible to govern without being pro-oil.

The NDP has provided a much cleaner face to what is a rapid expansion of oil sands and they acknowledge climate change, but it is performative politics. This is similar to Trudeau, who, as much as he promoted Truth and Reconciliation, is very much behind the tar sands, which Indigenous communities have protested against and don’t benefit from. The Kinder Morgan pipeline is going through territories where they don’t have consent to do that and Trudeau has stated that it’ s an “issue of national interest” and therefore, the pipelines are OK.

JC: Did anything prepare you for what happened in Fort McMurray — because, in the book, it seems you experienced some surprising stories?

AJ:I grew up in Williams Lake, B.C., and my father was a lumber grader. Matt also grew up in a working-class neighbourhood. I used to play volleyball and visited all these small communities in B.C., so I’m used to being in small towns.

However, I’d have to say it was eye-opening to experience the sheer diversity of the people living there, they are from all parts of the world. There’s a huge African community, (and) Muslim people, as well as a large Filipino population. If you visit one of the big community complexes, you’d see all kinds of kids, Muslim kids, playing hockey. I mean anything you see that is positive in community life, you find it there.

People are obviously there to make a living and make money but it’s everything you have in the immigrant experience of Canada. There is a kind of resoluteness and community building attitude. They have a motto: We are a hometown not a boomtown.

JC: Can you highlight someone from this journey that made a deep imprint on you?

AJ: We met this remarkable woman, Melissa Herman. She’s an amazing Indigenous woman who works for a number of non-profits there. Her family comes from the Janvier reserve which is about 1.5 hours south of Fort Mac.

We saw how much she contributes to the town and at the same time, she’s trying to support her own community, which is very much cut off from the economic benefits of the tar sands. It’s a paradox and a dichotomy that people live with every day. So many people are just trying to pay off loans or use the money to start a business elsewhere.

The median household income on the Janvier reserve is far below the poverty line while the median household income in Fort McMurray is $190,000/year. We have a stark difference in terms of what an oil boom means. Who bears the social and health costs of this expansion?

We went to visit her family. I remember when we were driving into the bush from Janvier to go to lake to pick blueberries. When we started walking, we could see there was a lot of discarded pipeline equipment sitting around. This detritus can leave sour gas, wildlife can lick it, it can seep into the food and water supply.

Melissa’s Uncle Dennis made this comment I’ll always remember: “Why don’t they just bomb us and get it over with?”

JC: This leads us to Ecuador, which gets major ink in your book. There was an attempt to focus on Indigenous peoples and land rights, is this something we should look to?

AJ:This is directly connected to the subtitle of our book: “The sweetness of life.” We are invoking a philosopher who was looking at Europe and the divide between the North and the South. Eduardo Gudynas talked about quality of life or wellbeing as not just about the individual but the concept of Buen vivir, about the individual’s wellbeing connected to their environment. And this bears out considering how people in Southern Europe live: they have a different relationship to time, to nature and to define life as something outside of work.

In Ecuador, there was a minister, Alberto Acosto, who worked on inserting the rights of mother nature into the (country’s) Constitution. Alberto, who is an economist, was the energy minister in 2007. He made a case for keeping the oil in the ground and asked for international organizations for support financially for the transition period. He put out an important question: What would be the circumstances if we decide to leave the oil in the ground? Alberto used the traditional (Quechua) indigenous principles of Sumak kawsay, (living together in diversity and harmony with nature), at the heart of the constitution.

He mapped out how we talk about creating an economy that is very different. Often times when we discuss climate change, the politics of land rarely gets talked about, and Indigenous communities have such a rich history connected to that and can put out pragmatic solutions for recovering nature.

Ecuador tried this but it fell apart. However, it does show us a route forward, i.e. what an environmental approach can look like. It opens up how we talk about this issue.

There is the other side of the argument when we talk about getting away from oil production. When the book came out (in March) we got contacted by an Alberta group that is arguing a financial basis for an alternative. They talk about the real opportunity costs of maintaining this industry. Canada’s chartered banks are exposed to more than $100 billion in what they have in financing the tar sands. There’s also the environmental cleanup costs which is in the tens of millions and not on the balance sheets of these companies.

We never seem to talk about government subsidies to the industry. What if we took that money and invested it into transitioning the economy?

Trudeau, in speeches to business groups, has said, there’s no country in the world that would have this kind of oil reserve and leave in the ground.

That’s really old 19th- (or) 20th-century thinking!

Excerpt from Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life: A Tar Sands Tale by Matt Hern and Am Johal, with Joe Sacco (MIT Press, 2018):

“A sweetness of life has to stare down capital and be able to articulate real alternatives. The energy to confront global warming has to come from outside the state, from everyday people everywhere, from popular and grassroots movements, and our contention is that they will be most successful when land politics are always front and center, these arguments have to be able to speak directly to workers in Fort Mac. Ecology cannot rest on shame and discipline; it has to offer an affirmative vision of change and a future that is material. A sweetness of life has to present itself as a living alternative to those who are being buffeted by incredible anxiety, volatility, and debt. Supporting Indigenous land struggles and land justice movements is not just a question of justice; it opens up space for all of us to imagine a different way of being in the world.”

Buy Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life: A Tar Sands Tale here

Images: Joe Sacco illustrations from ‘Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life: A Tar Sands Tale’ (Courtesy of MIT Press). Images have been cropped.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.