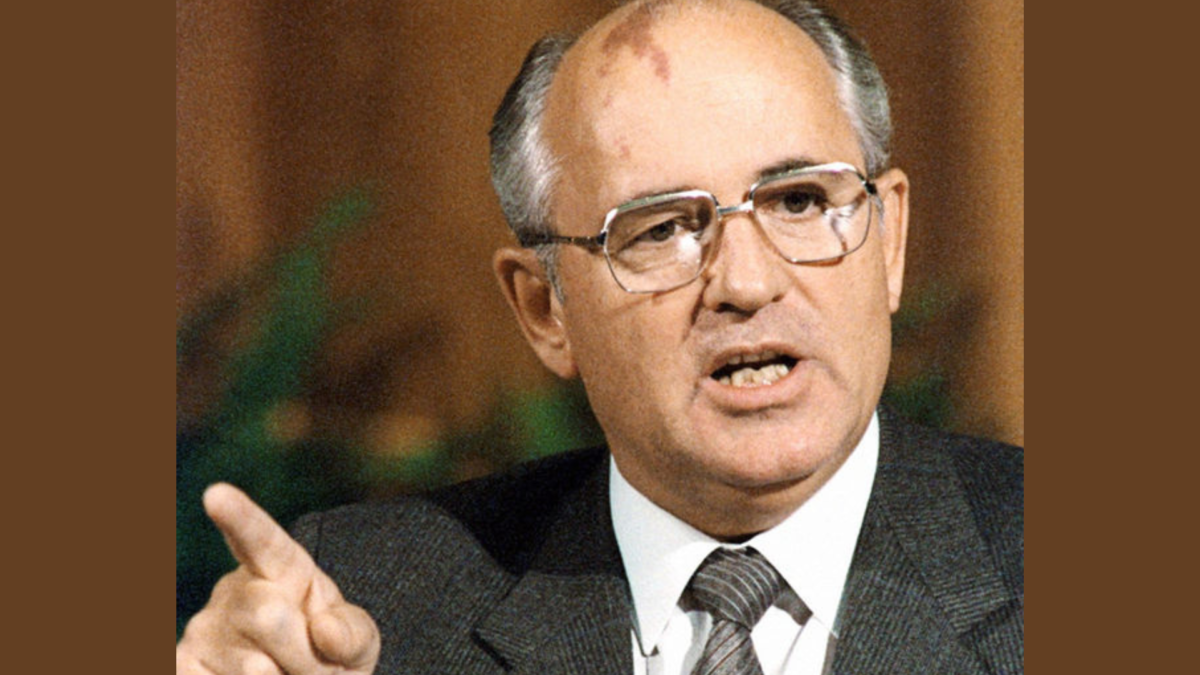

I was saddened this week, not just by the death of former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, but by its reception. U.S. news shows at first didn’t mention it, then gave it clichéd, unserious treatment. As if he’d been merely another Alexander Kerensky, Russia’s failed first leader after the czar’s fall in 1917, who spent his last decades in New York and died in the ER at St. Luke’s.

The clanging theme was: he was appreciated by the West but reviled in Russia. A tad self-congratulatory? Did Russians really loathe the openness Gorbachev gave them, or did they simply resent an immediate decline in living standards and mortality rates due to capitalist “shock therapy” imposed by western experts? From 1990 to 1994, life expectancy for men dropped by six years.

When alcoholic, pro-West Boris Yeltsin looked certain to lose the 1996 election, the U.S. recruited advisers to run his campaign — plus a $10 billion IMF loan which served as “a major election-year boost” for Yeltsin. U.S. journalist David Shribman intoned in the Globe this week that Gorbachev “couldn’t manage” the “transformation” he started. He overlooked how the U.S. managed Gorbachev’s failure to manage what he’d started.

Gorbachev knew a democratic transformation meant Russia must feel safe from invasions, like the Nazi one that killed 27 million Russians. So he secured a U.S. promise of no NATO expansion in return for dissolving the military Warsaw Pact. NATO expanded anyway. The whole nexus made Vladimir Putin virtually inevitable.

Now we’re back to the mutual vilifications of the Cold War, as if those remarkable transformations never happened. Career intelligence maven Graham Fuller says there’s a U.S. “media blitz” over Ukraine that amounts to “full-scale demonization of Russia … I never saw anything like this … during the Cold War.”

As someone who lived through the Cold War, though not as a player, I tend to differ. The vrai Cold War destroyed many lives and careers of earnest, innocent people, maligning them by association with, say, unions or the peace movement. Even Canada had a Hollywood-style redscare at the National Film Board: budding cineastes were fired and withdrew into more private lives.

As a kid in the early 1950s, my most poignant memory is of a comic book. It was about the Korean War. A wounded U.S. soldier helps a Russian — or maybe Chinese — soldier who in return kills him. As he breathes his last, he aches to tell the folks back home that, “They really aren’t like us. They’re evil.”

It’s this essentialism that underlies most demonization. You are what you were born to; change is impossible. It’s what makes Gorbachev’s noble efforts seem pointless. Poor guy, he even got to see it all revert before he died.

It suggests a Manichaean dualism is in our nature: an inescapable tendency to see good versus evil. We’re hopeless, but we can at least bravely admit it.

Yet I’ve been reading the late anthropologist-anarchist David Graeber’s recent book, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity,” written with David Wengrow. They challenge all that. Previous wisdom held that in humankind’s early days, small bands of hunter-gatherers were so poor there was nothing to fight over, so they co-operated and lived in peace. But with the rise of agriculture came conflicts about who would appropriate the “surplus,” along with monarchies, states, armies and cities to enforce the wealth grab.

Recent research seems to question that. In those “primitive” eons of hunting and foraging, there were indeed large cities and surpluses, but often without central rulers, mind-controlling religions or repressive armies. If so, humanity is in its essence as capable of co-operation and community as it is of conflict, hate and tyranny — even in conditions of plenty, not just scarcity. So we aren’t doomed to darkness. The question then becomes, How did we get “stuck” with a consensus that history’s only possible outcomes are hierarchy, war and Manichaean dualism? And can we free ourselves from such delusions?

Hm, hope is always welcome, especially with evidence. RIP, Gorbachev.

This column originally appeared in the Toronto Star.