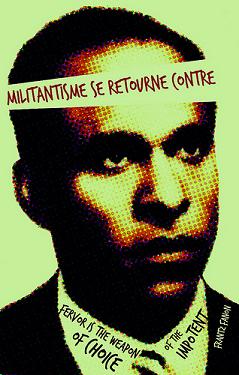

Last week, a friend of mine, Stefan Bird-Pollan, an Assistant Professor from the University of Kentucky, presented an insightful paper on Frantz Fanon at the University of Toronto’s Jackman Humanities Institute. Fanon was one the 20th century’s most influential anti-colonial theorists. He was born in Martinique, trained to be a psychiatrist in France, worked for the French government in Algeria, resigned his position, joined the Algerian National Liberation Front, wrote The Wretched of the Earth, and died of leukemia at the age of 36 in 1961.

While The Wretched of the Earth was very influential on anti-imperialist, civil rights and Black consciousness activists in the 1960s, it was his earlier book, Black Skin, White Masks, that has been the more influential to the fields of cultural studies and postmodern postcolonial theory since the 1990s. In the latter book, Fanon focused on racism’s impact on the psyche of the colonized, noting that the colonial context excluded the possibility of being a normally functioning, “well-adjusted” individual. The book’s chapters cover the role of language, inter-cultural relations, dependency, experience, psychopathology and recognition in internalizing racism in the colonized and consolidating a paranoiac, superiority complex in the colonizer. In the conclusion of the book, Fanon stated, “The Negro is not. Any more than the white man,” meaning that the process of investigating the psychopathology produced by colonialism enabled one to become aware that racial identity was historically constructed rather than biologically innate. The dissection of racial representation released Fanon — and his readers — by turning the body from being a structural factor of consciousness to becoming an object for consciousness to understand, evaluate and re-imagine.

Fanon — with typical introspective honesty — concluded that a medical doctor’s quest for dis-alienation — his own — was fundamentally different from that of a poor, black labourer. He would take up the situation of the latter in The Wretched of the Earth where he would emphasize that only political revolution could fully decolonize the psyche of a subordinated population. He contended that the colonial situation produced a weak ego, that is, one that could not reconcile its conditions and thus became more prone — even desirous — of ideological manipulation. Fanon however also explained that the more stripped the ego was of its defences, the more likely that the colonized would eventually revolt against his or her conditions: domination seemed to establish a curious dynamic by which it first encouraged one to submit to a master but then as subordination reached a maximal point a reversal occurred, producing an analogously violent rebellion against the oppressor. The colonized, having once abandoned their own culture to adopt the colonizer’s, would now in their insurgency also abandon the latter in order to hopefully embrace a new emancipatory culture.

Empirically we know now that Fanon was only partially correct: colonization sometimes produced political mobilization from the colonized and when it did it was only among certain groups in certain regions. Revolution tended to come from those areas — that were not necessarily the most subordinated — but that had collective institutions, a tradition of activism, and importantly an alternative symbolic order. Rebellion has never been simply an act of negativity but has also always been informed by an image of another, potentially more fulfilling world.

Fanon’s work also needs to be rewritten today because the popular interpretation of what it means to be “Black” has gone through a significant transformation. The activists that were influenced by Fanon altered the broader meaning of the term: today working-class and middle-class white youth, as well as other ethnic groups from around the planet — from Parisians to Palestinians — use the language, sounds, tones, figures and images of African-American hip-hop culture to symbolize their rebellion against various forms of authority. “Black Skin, White Masks” has also become “White Skin, Black Masks” or “All Skins, Black Masks”. “Black” culture, once regularly derided, has now — because of the work of organizers, artists, writers, teachers, journalists and others — produced the alternative codes that the marginalized, the young, or just the restless, emulate in order to articulate, revise or even salvage their own identities.

Thomas Ponniah was a Lecturer on Social Studies and Assistant Director of Studies at Harvard University from 2003-2011. He remains an affiliate of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies.

Image: mauldinart/Flickr

What’s Harper up to? Award-winning journalist Karl Nerenberg keeps you in the know. Donate to support his efforts today.