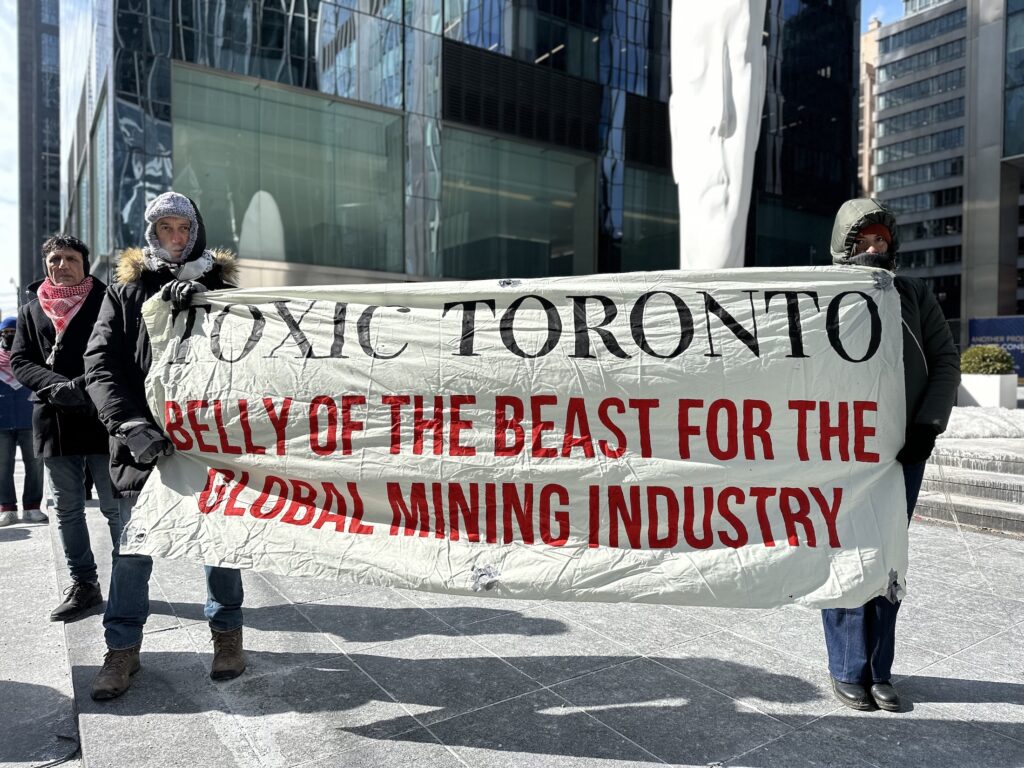

“People around the world are paying attention to what is happening here in the belly of the beast,” Rachel Small, Canada organizer for World BEYOND War and member of the Mining Injustice Solidarity Network (MISN), said on the steps of the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX), where forty percent of the world’s mining companies are traded.

From March 2 to March 5, the Toronto Metropolitan Convention Centre hosted the world’s largest mining conference. The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) convention drew 27,353 participants and over 1,100 exhibitors from the private sector and state governments.

As the convention kicked off, a protest organized by MISN denounced the greenwashing of the critical minerals sector and its role in fuelling militarism. In solidarity with Wetsuwe’ten land defenders and Chilean, Congolese, Palestinian, Sami, and Sudanese activists, roughly a hundred people marched through Toronto’s Financial District. Unlike in 2023, they didn’t infiltrate the convention centre.

“Canada is going to start exporting resources that are extracted from Native lands out of the Hudson Bay because it cuts shipping exports by 8,000 km anywhere across Mother Earth,” activist Clayton Thomas-Müller of Pukatawagan Cree Nation said, denouncing how the Churchill Port is bringing a renaissance of colonization to northern Manitoba.

“Where we come from, we are a fishing and a hunting people, and we need water to be healthy,” he said, stressing the looming impacts of industrialization on the region’s pristine lakes and rivers.

The Churchill port is the only Arctic seaport serviced by rail and has long been on the margins. Privately owned by the Arctic Gateway Group (AGG), a consortium of Indigenous and community shareholders, the remote port’s growth is now expected to be exponential.

The first international critical minerals shipment crossed the Hudson’s Bay in August 2024. As PDAC unfolded, the AGG signed a deal with Hudbay Minerals that doubles the volume of critical mineral shipments, with other agreements on phosphate and ammonium sulphate made in the days following. The port is also tripling critical mineral storage capacity.

With global demand for critical minerals expected to double by 2030, PDAC emphasized critical mineral exploration in northern regions of Canada. Countries are currently aiming to reduce dependency on Chinese supply chains and conflict minerals. But there are other motivations beyond conflict-free cars, phones, solar panels and windmills. Bullet and missile manufacturers are facing global shortages for metals like antimony, and NATO countries are under pressure to meet spending targets.

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy emphasizes self-sufficiency and national security in the Canadian minerals sector. Already committing up to $3.8 billion over eight years to critical minerals development, the Canadian government renewed significant commitments to develop the sector on March 3, announcing a two-year extension of the Mineral Exploration Tax Credit until 2027, expected to provide $110 million to exploration investment.

Activists invoked the image of Toronto’s financial district as a pulsing mining capital. But behind the doors of the TSX, the story is looking a little different.

Canadian mining companies have actually been leaving Toronto to trade on foreign stock exchanges. Early last week, Bloomberg reported an exodus of Canadian mining companies amid Trudeau’s ongoing crackdown on foreign investment—recent moves including shifting headquarters to Switzerland, Ecuador and Abu Dhabi. Barrick is considering relocation to the U.S., with other moves in progress. And this is happening as larger Canadian companies like Teck have been warding off hostile foreign takeover.

So while demonstrators denounced Canadian mining companies profiteering from war and complicit in human rights abuses abroad, some of those same companies are leaving the country, while Canada itself is becoming a target for foreign companies and takeovers amid an intensifying critical minerals race.

Exporting green militarism

While the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy emphasizes Canada as a source of conflict-free resources, much less is said about minerals’ uses and destinations.

“We know that their business as usual is a world with even greater wealth inequality,” MISN’s Small said. “It’s a world where Indigenous people are removed from their land at gunpoint so Canadian companies can dig up critical minerals used to make the bombs that are bombing other Indigenous people, on their lands, around the world.”

“We’re seeing that become more and more unmasked,” MISN member Miriam Shaftoe told rabble.ca. “In Canada, even before Trump got in, we were increasingly seeing direct investment from the U.S. defence industries into mining projects in Canada.”

“Every F35 fighter jet has about 900 pounds of rare earths in it,” Shaftoe explained. “Those weapons are being used to bomb civilians in Gaza. It’s that cycle of violence—from extraction to the final product—[where] we see the Canadian mining industry entangled at all stages.”

Activists called for arms embargoes, such as those against Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), to explicitly hold the mining sector accountable.

“The struggles faced by our Indigenous comrades due to the horrible impacts of Canadian mining companies share significant parallels with the Palestinian liberation struggle where land, identity and sovereignty are at the core of the fight for justice,” Adam Diabas, activist with the Palestinian Youth Movement, said, flanked on all sides by Canadian bank headquarters.

“We will continue to call for an arms embargo in this upcoming federal election,” Diabas said, calling for pressure at all stages of weapons supply chains. “We are calling for the companies that provide the materials for the weaponry to be sanctioned.”

“The companies claim that extracting minerals like diamonds, cobalt, coltan, and gold in Indigenous territories make them no longer conflict minerals,” said Nisrin Elamin of the Sudanese Solidarity Collective.

“From Sudan to Turtle Island, these are not conflict minerals. They are genocide minerals,” she said. “It is therefore our duty as people living in proximity to the headquarters where this consortium of corporate murderers sit comfortably, plotting how to up their profits through our death, to disrupt their business as usual.”

Sovereign sacrifice zones

Inside the sprawling convention centre, mining leaders just want to drill. Government officials solicited investment. Investors speculated over the rising prices of silver and gold. All eyes were on Trump’s audit of the Fort Knox gold reserve.

And while demonstrators demanded the right to refuse mining projects, Indigenous panelists inside were focused on increasing negotiation power and becoming project shareholders.

“Any resource development that happens in Canada, or across Turtle Island for that matter, happens on the traditional lands of the Indigenous peoples here,” said Saga Williams of the Curve Lake Anishinaabe First Nation.

Williams is a member of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC), a national organization representing over 175 First Nations communities across Canada. One of the coalition’s campaigns is to secure Indigenous equity in infrastructure and mining projects worth over $100 million (CAD). “It’s not unrealistic for our communities to be expected to be a part of that,” she said.

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy positions Indigenous participation in the minerals sector as a form of economic reconciliation and environmental stewardship. Williams called for recognition of Indigenous sovereignty in environmental assessments and respect for sovereign Indigenous authority under section 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

“The more that we support and ground ourselves in that space of inherent rights and Indigenous knowledge, the better partners we will be in industry and in resource development within this country,” she said.

Stuart McCracken, Vice President of Exploration at Vancouver-based Teck, described how the mining company is respecting Indigenous sovereignty in Peru—where they operate the Antamina copper and zinc mine, one of the largest in the world—by circumventing the state.

“So if we enter in the area and we stake some land that has Indigenous people, under the legislation in Peru, we must immediately go into previous consultations,” he said in a panel.

“What we do, rather than just leaving the Minister of Culture to run that process—and that can take up to two years for them to do that,” McCracken explained, “We will immediately go toward the Indigenous community to really understand what their needs, their concerns, their limits are, and whether there’s an agreement to be had.”

“We recognize that we, as a company, can enable both the Indigenous population but also the government system to be more successful,” he said.

“We want to build and access critical minerals. We can do this in a responsible manner, ensuring that our critical minerals are sustainably sourced,” said Katherine Koostachin, Vice President of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation at the Sussex Strategy Group. “If you want to accelerate critical minerals, you have to ensure Indigenous nations are at the table.”

Koostachin took a pragmatic stance on Indigenous participation in critical mineral development, while stressing that many of the uses for minerals, like electric vehicles that can’t withstand northern climates and terrains, don’t actually serve Indigenous communities.

It remains to be seen whether this also applies to missiles made with niobium, tanks using thorium, ammunition using cadmium, missiles made with antimony, or nuclear weapons made with graphite. But industry leaders at PDAC were clear about their goals.

“Really, it’s a question of how can we progress our project so we can eventually mine,” said Claudia Tornquist of Kodiak Copper. “The key principle is balance between consulting, engaging, mitigating, and moving forward.”