There has been slew of recent news stories in the press about how the austerity experiment in Europe and to a lesser extent in North America has utterly failed. Left-wing economists, such as Dean Baker and Paul Krugman, have repeatedly hammered home that the economic rationale behind austerity is baseless. The New Yorker even just published a story declaring austerity has failed. What is actually missing from the austerity debate is not a critical take on the technical outcomes of austerity as a policy, but a political understanding of social policy itself.

The recent news of the debunking of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s oft-cited study, “Growth in a Time of Debt” which postulated that countries with a debt–to-GDP ratio over 90 per cent experienced negative economic growth, has given the critics of austerity yet more ammunition. The study, which was based on looking at a variety of countries’ economic performance in relation to their debt–to-GDP ratio, was flawed on a number of fronts. It used controversial weighting measures, it had an indiscernible criteria for selection and exclusion of subject countries, and it contained a major spreadsheet error.

The heavily cited study has been used as a justification for austerity policies around the globe. The 90 per cent debt–to-GDP ratio has functioned as a reference point for the debate around austerity measures here and abroad. The more a nation moves beyond the tipping point, the more its public sector should be cudgelled, or so the theory goes. In Canada, where our debt-to-GDP ratio is roughly 85 per cent, we have been largely spared the deep cuts of European-type austerity and have only undergone a version of austerity lite during the current reactionary period (we of course were the subject of deep economic restructuring in the early 1990s).

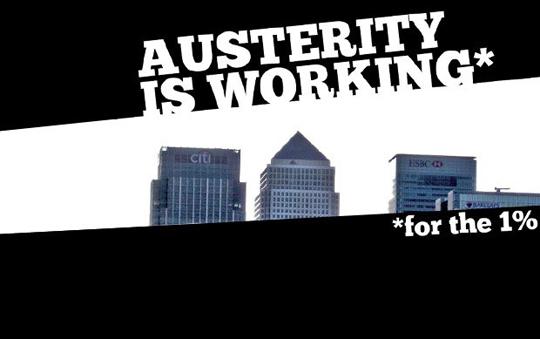

The problem is that this reading of austerity as not working papers over the political trappings of the word “working”. Who is austerity supposed to be working for? What is it supposed to be fixing? The point here is that the very understanding of social policy as a politically neutral undertaking should be questioned. Austerity is a political answer (a very temporary and contradictory one at that) to a series of political and economic problems. So when we question austerity, we do it from a political position whether we realize it or not.

Austerity is not aimed at raising all boats or creating the conditions for full employment. It is being used to further extend the power and profits of those at the top. In certain situations this has backfired by greatly increasing political instability as in Greece. Though by and large the austerity response has worked: profit levels have been somewhat restored, big companies are flush with cash and the stock market is roaring along.

Again it must be stressed this isn’t a rational policy response to the crisis, it is a ruling-class response. Thus, it contains all sorts of contradictions that make austerity at best a temporary fix to some of the deeper structural tensions within the capitalist economic system. In Canada, for instance, our unemployment rate remains relatively high, though slightly recovered, but the benefits and wages of workers have stagnated or fallen. This poses a problem of sustaining effective demand, especially in the Canadian housing market.

Pointing out the gap between the publicly stated purpose of austerity, economic recovery, and the actual result, growing disparity between the rich and the rest, can be a useful exercise in political practice. That gap can be used to open up a wider discussion about who makes policy decisions and why. However, parts of the left have confused a useful political practice with an actual political analysis. This confusion has lead to a real poverty of discussion about what should be done and how should we do it.

By positing austerity as not working and stating that we simply need a better public policy to deal with the economic crisis, we are depolitizing the class struggle in relation to social policy. A simple return to Keyenesian policies will not solve the deeper structural problems of capitalism, nor do they address the competing class interests when it comes to economic questions.

We need to use the gap between austerity’s outcomes and its public defence as part of a strategic push to open a broader debate about the workings of capitalism and the state in Canada. We need to do this without falling into this gap. Otherwise we run the risk of short-circuiting the political dimensions of social policies, for austerity isn’t the result of a math problem, it is the result of political struggle.