At a campaign stop on Friday morning, Ontario Progressive Conservative Leader Tim Hudak pledged to cut 100,000 jobs from the public service in Ontario in order to balance the budget.

According to The Globe and Mail’s description of the announcement, “Mr. Hudak did not say exactly which jobs would be cut, but promised not to touch doctors, nurses or police officers. He suggested instead that he would mostly look to eliminate administrative positions and to privatize some services. The Tories have, in the past, talked about privatizing gambling and the LCBO, among other things.”

It’s easy for politicians to attack the public service and pledge to cut “government waste” to pay for other promises; however, delivering is much harder. As Alex and Jordan Himelfarb recently noted, “there’s never enough gravy.” Therefore, any assessment of Hudak’s pledge to cut the public service should start with the question: “Is this promise realistic?”

To answer that question, first consider the size of the Ontario public service: The so-called “core public service” in Ontario employs approximately 60,000 people — these are the public servants who would work in the departmental structure and are likely what you think about when Hudak promises to “eliminate administrative positions” — although many would work in front-line services, implementation or policy development.

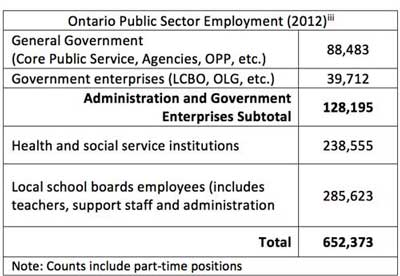

Including agencies, boards and commissions (such as Metrolinx, the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation, the Niagara Falls Bridge authority and several hundred other organizations) and provincial police and judicial employees, Statistics Canada numbers from 2012 place the number of Ontario public servants in the general government category as 88,483 (Statistics Canada, “Public sector employment,” CANSIM, table 183-0002. Average from January to March 2012). The OPP, which Hudak said he would not touch, consists of 9,000 of these positions. Hudak confirmed at his press conference that he would eliminate some of these agencies, including the Ontario Power Authority, Local Health Integration Networks and the College of Trades.

Since Hudak says some of the job cuts would come from privatization, some of the 100,000 could come from the 39,712 people — including part-timers — employed by “government enterprises” such as the LCBO, the OLG and provincial parks. Of course, many of these government enterprises are revenue-generating, so privatizing them might decrease government revenues more than they cut costs.

Now here’s a scary number: If Hudak’s job cuts were to come entirely from eliminated “administrative positions” and privatization, it would represent a devastating 78 per cent reduction in this pool of workers.

The truth is that most public sector workers in Ontario work in the MUSH sector (Municipalities, Universities, Schools and Health). The health and social services sector in Ontario employs 238,555 people and, while Hudak said he wouldn’t cut “doctors [or] nurses” specifically, it is possible that some of the staff cuts would come from this sector. Indeed, in 2012, Hudak promised to close Ontario’s LHINs and Community Care Access Centres, which he estimated would cut 2,000 health administration positions.

The largest government employers in Ontario are actually the local school boards, which employ teachers, support staff and educational administrators. Together, Ontario’s school boards employ 285,623 people. A PC white paper on education released in January 2013 suggested cutting 10,000 “non-teaching positions” and delaying full-day junior kindergarten until the budget is balanced (Paths to Prosperity: Preparing Students for the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century, p. 20). The white paper’s conclusion said: “Education is vitally important, but we can’t pay for it with borrowed funds. As Don Drummond recommended, that means increasing class sizes a bit, eliminating some non-teaching jobs and controlling the cost of full-day kindergarten while we see if it really works.” At his press conference, Hudak confirmed that teachers would be on the cutting block saying: “Will it mean fewer teachers? It does.”

The post-secondary education sector and municipalities also employ a large number of Ontarians, but it’s likely that these areas would be harder for Hudak to cut. The government could starve funding to municipalities or universities, but it wouldn’t guarantee job cuts since they have independent budgeting processes and other non-provincial revenue streams.

The breakdown of the Ontario public employees is as follows:

If Hudak’s cuts to the public service are going to come from core government, government enterprises as well as health and education sectors, then firing 100,000 workers would represent a 15.3 per cent cut in these areas. Excluding “doctors, nurses or police officers” from this group, the cuts would represent 18.9 per cent of the remaining public sector.

To put these promised cuts in perspective, according to a recent report by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, the total federal public service cuts since March 2010 have amounted to about 20,000 FTE positions, with an additional 8,900 positions scheduled to be eliminated by 2016-17.

I’ll leave it to readers to determine if they think this a realistic promise, however, if such cuts were implemented it would be unrealistic to think services would be unaffected and it would ultimately mean 100,000 fewer good paying middle-class jobs in Ontario. And, with the economic multiplier effect, firing these public servants would decrease economic growth and hurt jobs in the private sector.

(iii) Statistics Canada, “Public sector employment,” CANSIM, table 183-0002. Average from January to March 2012.

Kayle Hatt is a Research Associate with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ National Office and was the CCPA’s 2013 Andrew Jackson Progressive Economics Intern.

Photo: Laurel L. Russwurm/flickr