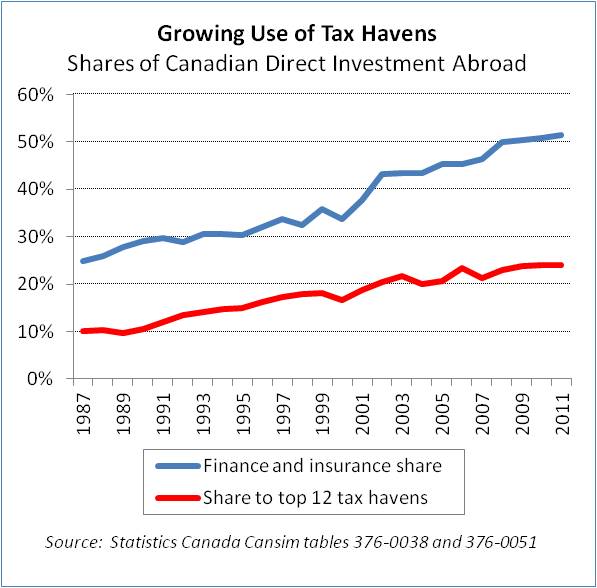

A growing share of Canada’s investment overseas is being channelled by Canadian banks into tax havens.

The latest Statistics Canada figures show 24 per cent of Canadian direct investment overseas in 2011 went to the top 12 tax havens, up from 10 per cent in 1987. In fact, tax havens of the Barbados, Cayman Islands, Ireland, Luxembourg and Bermuda were five of the top eight national destinations of total Canadian investment abroad, with the U.S., U.K. and Australia the only countries not considered tax havens in this group.

To put this in perspective, over $390 billion of Canadian “investment” has flowed into Barbados in the past decade, with precious little coming back. That’s $1.4 million for every resident of that island, but you can be sure that very little of this actually flows to the people there. Over $175 billion of Canadian investment has gone to the Cayman Islands in the past decade, equal to $3.2 million for each of the island’s residents.

These totals would be even higher if they included figures for other tax havens such as Monaco, Liechtenstein and many others where the figures either aren’t available or weren’t made available for confidentiality reasons. They also don’t include money going to tax havens associated with the U.K. and the U.S., such as Channel Islands, or through banks in those countries.

The finance and insurance sector now accounts for over 51 per cent of Canada’s total direct investment overseas, more than double its share from 1987, more evidence that a large share of this money is going overseas to avoid taxes. The Harper government has lauded Canada’s growing investment overseas, claiming it shows looser foreign investment rules (which allowed numerous takeovers of Canadian industry) have been beneficial, but the actual figures show the reality is quite different. A large and growing share of this money isn’t going into real capital investments that could ultimately benefit people overseas or in Canada; it’s going into tax avoidance that benefits a wealthy few at the expense of the large majority in Canada and around the world.

Last month, James Henry — former chief economist of McKinsey & Co, the top corporate consulting firm in the world — released a report he wrote for the Tax Justice Network, The Price of Offshore Revisited, estimating that $21 to $32 trillion is held in tax havens worldwide. This amounts to an estimated $190 to $280 billion of lost income tax revenues annually: more than twice the amount all OECD countries spend on international development assistance worldwide. Poor and developing nations are especially harmed by tax havens, as they are extensively used by political and corporate kleptocrats and multinationals operating in those countries to avoid taxes.

CBC’s The Current radio show had a very good interview with James Henry about this issue on Aug. 16 and with Alain Deneault, the Canadian author of Offshore: Tax Havens and the Rule of Global Crime. Another major attraction of tax havens is of course their secrecy, which enables not just the wealthy to avoid taxes, but also criminals to both avoid taxation and prosecution.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much evidence our political leaders are doing much about this as the problem continues to grow. As Alain Deneault said, they always go after the small people on taxes. Meanwhile, high profile politicians such as former Conservative Finance Minister Michael Wilson chairs the Canadian operations of international banks such as UBS and Barclay’s that do a lot of business in tax havens — and recently refused to appear before Commons committees examining this issue.

The use of tax havens is also fuelled by and exacerbates growing inequalities of income and wealth: highly affluent individuals and corporations with a lot of excess money they aren’t productively investing back into the economy or spending on their needs. Canadian banks have also been complicit in building up some Caribbean nations into tax havens — and use them to avoid billions in tax annually themselves, as Quebec economists Leo-Paul Lauzon and Marc Hasbani showed when they examined the annual reports of Canada’s big five banks a few years ago.

Canada’s House of Commons Finance Committee will be examining the issue of tax havens again this fall. It’s a growing problem with real consequences, especially as governments cut public spending ostensibly to tackle their deficits. Hopefully they will be able to make more progress this time and stem some of this flow. Otherwise this dirty little secret of Canadian banks is going to grow a lot bigger.

Notes: Figures on FDI are from Statscan Cansim table 376-0051 (by country) and 376-0038 (by industry), available to download for free. The Congressional Research Service has a list of countries considered tax havens in their relatively recent report, Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion.

This article was first posted on the Progressive Economics Forum.