In the Throne Speech in June, the Harper Conservatives presented Canadians with their priorities for the coming year. High on their list is the securing of an economic partnership with the European Union, the CETA (comprehensive economic and trade agreement). Negotiations between Canada and the EU began in the summer of 2007 and are set to conclude in 2012.

The agreement is about a good deal more than tariffs and the cross-border flow of goods. CETA will involve such broad matters as investment, government procurement, energy, telecommunications, the environment and intellectual property. The purpose of the agreement, according to its crafters, is to enhance national competitiveness and prosperity.

It is striking to note the absence of public meditation over the CETA. Contrast this with two decades ago when Canada was convulsed in debate over the prospect of a North America-wide trade and investment liberalization regime. The stakes were high back then and no one pretended otherwise.

The advocates of CETA are marketing the agreement on the apparent success of NAFTA. But was NAFTA a success? It is often assumed to be so, but few bother to identify the criteria they employ when evaluating it.

The pedigree of ideas can have no more exacting a judge than reality itself. Canadians would do well to recall what the advocates of trade and investment liberalization promised some two decades ago: a decrease in unemployment; an increase in “real” GDP; a boost to long-term productivity growth; and, on the question of distribution, the explicit assumption was that gains from trade would be widely shared with workers in the form of higher wages. Every one of these promises failed to materialize. In the two decades since the instituting of a trade and investment liberalization regime, Canadians have witnessed worsening employment opportunities, heightened stagnation and redistribution from wages to profits.

The question emerges: if trade and investment liberalization has been a failure by broad social criteria, then why do its champions continue to advocate on its behalf? The short answer is that it has been a success… for some. A longer answer is based on a relationship that economists often fail to notice: heightened corporate concentration and rising income inequality.

Over the course of the 20th century, North America was transformed by the emergence of big business. Firms grew in relative size primarily by merging with or acquiring other firms. Corporations expanded first in their own industries, then across sectors and finally pushed up against national borders through the formation of giant conglomerates. Having become national in scope by the 1970s, continued expansion (of ownership) required a new universe of take-over targets, hence the political engineering of globalization (i.e., the internationalization of ownership and control).

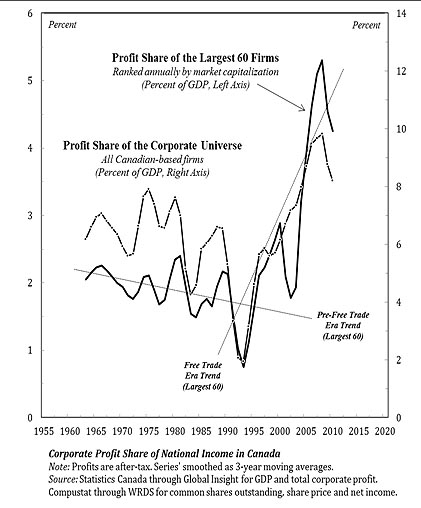

Larger relative firm size coupled with enhanced capital mobility leads to greater pricing power and better enables business to resist unionization and wage demands. The combined effect is stagnant wages, thicker profit margins and a higher profit share of national income (see chart above).

The mere existence of larger firms, then, affects redistribution: from labour (in the form of wages) to capital (in the form of profits) and from the bottom 99 per cent to the top 1 per cent of income earners. It is the latter group that owns and has effective control over the corporate sector, thus explaining the enthusiasm some have for CETA.

All of this will be deflected by CETA’s advocates. But their immunity to these discomforting truths paired with their amnesia about the broken promises of NAFTA needn’t be replicated by the broader citizenry. After all, it’s hardly novel to observe that states work to promote the interests of the powerful. Even Adam Smith understood perfectly well that “government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor.”

CETA will further empower global capital, weaken labour (whether organized or not), reduce the capacity of governments to protect the quality of life for Canadians and accentuate the trend towards radical income inequality and so, liberal-oligarchy. Having devoted his life to the study of the ancient Mediterranean world, Plutarch would famously observe: “an imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.” Canadians who have some regard for democracy would do well to conserve that bit of ancient wisdom.

Jordan Brennan is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at York University.