Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

In the spring of 2013, we studied the economic trajectories of Canada and Quebec following the 2008 crisis. I decided to update the data from this previous study to see how the situation has evolved.

Two years ago, the concept of the “austerity trap/stagnation” seemed to best describe the economic climate at the time: slow growth, a tax position weakened by a preference for tax cuts over revenue, and the attempt to balance the budget only through cutting expenses and investments, which reinforces the stagnationist tendencies of the economy. That was the vicious circle we were describing then; a vicious macro-economic circle which was neither inevitable nor necessary, but which stemmed from political choices, from a strategy adopted by governments in both Quebec City and Ottawa, who, since 2010, have been promoting policies favouring a balanced budget at a time when the economy has not yet recovered from the 2008-2009 recession.

The reality of austerity budgets

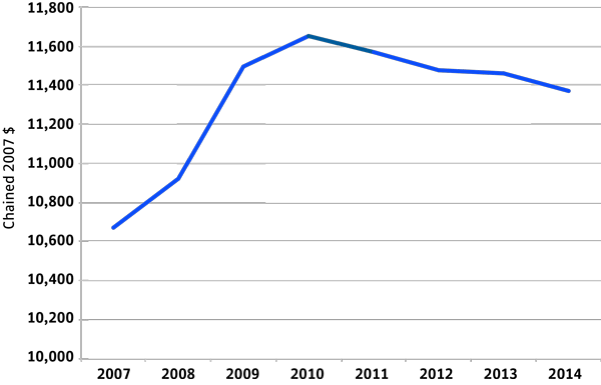

The shift in 2010 is unmistakably one towards austerity. In Quebec, per-capita public spending and investments at all three levels of government stopped increasing and began to trend downward, as shown on Graph 1.

Graph 1: Evolution of total public expenditure and investments in Quebec, 2007-2014 (in chained 2007 dollars)

Sources: Institut de la statistique du Québec (ISQ), “Produit intérieur brut réel aux prix du marché selon les dépenses, données trimestrielles désaisonnalisées au taux annuel, base 2007, Québec” (27 March 2015); ISQ, “Population, accroissement quinquennal et répartition, Canada et provinces, 1971-2014“, author’s calculations.

The budgetary and taxation policies of all three successive provincial governments have been characterized by this shift towards austerity since 2010, even if it slowed down slightly between 2012 and 2013 under Pauline Marois’s PQ government. In short, euphemisms notwithstanding — rigour, responsibility — we are undeniably under an austerity regime, and denying the fact in no way improves the debate on our current economic reality. We can of course debate the benefits of such policies as well as what their aim is and whether or not they are necessary, but we must start by acknowledging the fact that this is austerity.

The aggregate decisions of the successive governments have resulted in a net decrease in public expenditure in Quebec: that means trimmed budgets. This trimming does not come strictly, nor even mainly, from increased efficiency in state institutions; instead, it transforms the role the state plays in Quebec society. This is what the current Treasury Board president proclaims: the goal is to “reposition the state within Quebec society.” In his own way, Martin Coiteux refashions an old slogan used by the Liberal party: “We need a true cultural revolution,” as Raymond Bachand had said in 2011.

Economic stagnation

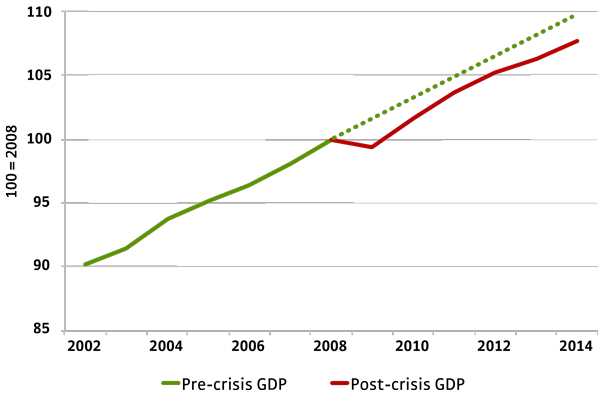

Where does that leave us today? On the macro-economic level, Quebec’s economy never totally recovered the losses in activity that occurred during the crisis. As shown on graph 2, our economic growth remains disappointing even seven years later. Quebec’s GDP is far from what it could be, if only we had closed in on the lag incurred during the recession, as was the case in 1982 and 1990, which we studied back in 2013. At the time, we spoke of an L-shaped recovery in contrast with the V shape we observed after previous recessions, and that is indeed the shape of the GDP growth curve.

Graph 2: Post-crisis GDP growth compared to pre-crisis trends, Quebec, 2002-2014

Sources: ISQ, “Produit intérieur brut réel aux prix du marché selon les dépenses, données trimestrielles désaisonnalisées au taux annuel, base 2007, Québec” (27 March 2015), author’s calculations.

A careful look at Graph 2 reveals that there was a short recovery period for the GDP that matches the stagnation period in expenses, as observed in Graph 1. However, in 2013, the trend for GDP growth returned to the lag it experienced at the end of the crisis in 2009, and continues to trail behind pre-crisis projections.

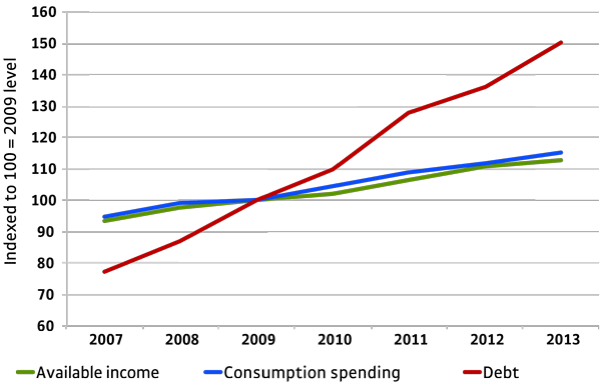

The only stable economic drive remains household consumption, but as Graph 3 shows, this translates into persistent consumer debt. Since family wages alone are not sufficient to cover all household expenses, credit cards are called in to take care of the rest.

Graph 3: Wages, expenses and non-mortgage credit in Quebec, 2006-2014

Sources: ISQ, “Compte des ménages, données trimestrielles désaisonnalisées au taux annuel, Québec” (27 March 2015), ISQ, “Valeur des prêts détenus par les institutions de dépôt, données annuelles, Québec“, author’s calculations.

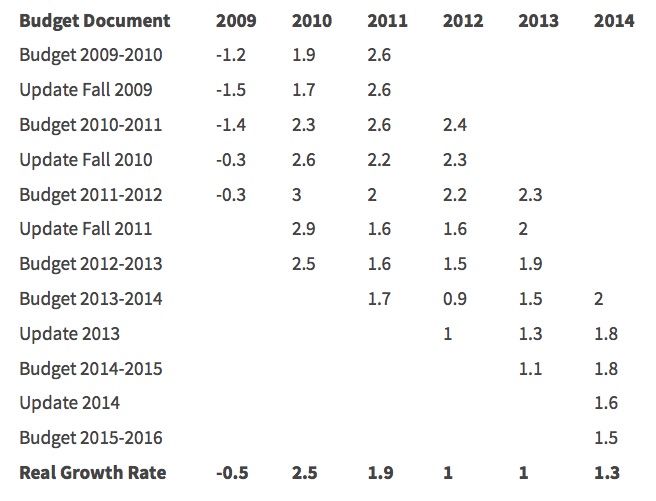

And yet, things should be very different for the economy at both Canadian and Quebec levels. We are promised budget after budget that budgetary restrictions and the state’s exemplary rigour will generate the confidence needed to restore the forces that drive private sector growth. One after another, Finance ministers tell us that business investments are about to bounce back, that household consumption is steady and will soon progress, and that our exports to the U.S. will issue forth strong and sustained economic growth. And each time our L-shaped recovery — a fate we share with both Europe and the U.S. — belies our government’s optimistic projections and the figures on which budgetary hypotheses are based.

Table 1 shows just how much projections for 2011 and the following years have been overestimated by the Finance department, from the 2009 budget documents on, and so until the most recent publications in March 2015. Incidentally, the last budget foretells once more an increase in growth starting in 2016, wagering on the same factors as before. The government is relying on a 2 per cent increase in GDP real growth, though available data shows a slight decrease in economic activity for February 2015.

Table 1: Growth predictions by the Finance minister, Quebec, 2009-2014

In short, the finance minister is constantly hoping for a growth that never comes. Graph 4 explains why the economic vitality hoped for never materializes.

Graph 4: Evolution of domestic demand factors, Quebec, 2002-2014

Sources: ISQ, “Produit intérieur brut réel aux prix du marché selon les dépenses, données trimestrielles désaisonnalisées au taux annuel, base 2007, Québec” (27 March 2015), author’s calculations.

Businesses are not investing a whole lot, and some are saving up too much. The vast majority of households spend what they’re earning, but don’t earn enough, so they get into debt. As a study published by IRIS shows, a minority, the 1 per cent, earns too much, and we can assume that this surplus is saved up rather than spent, thereby not contributing to growth. Government spending has been stagnating since 2010.

The markets to which we are supposed to export are equally stagnant. The United States in particular, a figure of salvation that is omnipresent in Quebec’s budgetary policy, is unable to reach a stable growth rhythm that could sustain our exports.

Furthermore, we are surprised to realize that what little growth the U.S. economy experienced following the Great Recession was grounded mostly in oil production, which represented close to 30 per cent in private investments, more than Canada’s 20 per cent. This explains the downturn in U.S. activity since the price of crude oil dropped. In sum, everything suggests that if growth is to pick up again in Quebec, we need to rely primarily on domestic agents rather than hope for a panacea in the form of foreign markets. Unfortunately, as we have just seen, such agents, in the private sector at least, are in rough shape, which is worsened by budgetary austerity.

The paradoxes of debt

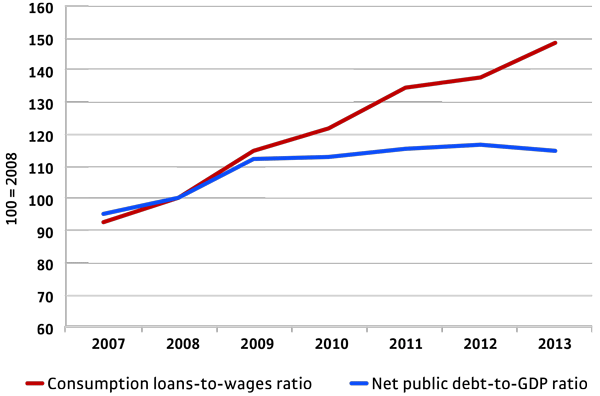

Austerity policy in Quebec is commonly justified by the need to decrease the national debt, the growth of which, we are told, is not only out of our control, but will also be an undue burden on future generations. However, as Graph 5 shows below, in terms of both weight and out-of-control increase, private household debt is clearly more worrisome than public debt.

Graph 5: Evolution of the net public debt-to-GDP ratio and evolution of consumer credit-to-wages ratio, Quebec, 2007-2013

Sources: Budget of Quebec, March 2015 (net debt / GDP); ISQ, “Compte des ménages, données trimestrielles désaisonnalisées au taux annuel, Québec” (27 March 2015); ISQ, “Valeur des prêts détenus par les institutions de dépôt, données annuelles, Québec“; author’s calculations.

The “weight” of debt is measured using a relevant denominator. In the case of public debt, this denominator is the size of the production monetary economy that sustains that debt, i.e. the GDP. To decrease the weight of public debt, one can choose to act upon the numerator, by reimbursing the net debt, or on the denominator, by stimulating growth in the underlying economy, which would increase the GDP, and therefore decrease the debt-to-GDP ratio. (IRIS has produced a pamphlet on the subject.)

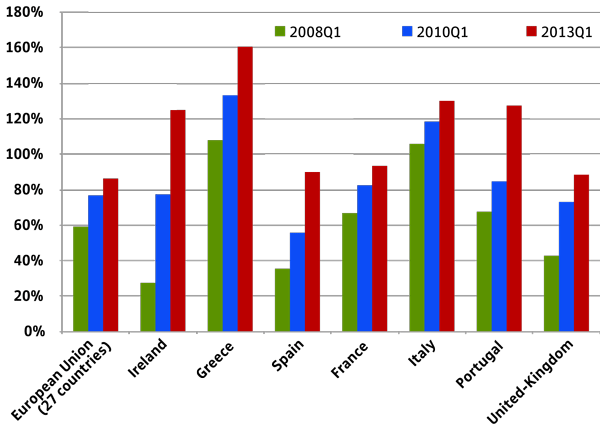

Austerity governments like our own choose to act upon the numerator and tackle debt by reducing expenses to balance the budget. However, European countries that have been down the same austerity path since 2010 demonstrate that such an approach paradoxically results in an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, as shown in Graph 6.

Graph 6: Debt of various European countries (2008, 2010, 2013)

Source: Eurostat, Quarterly government debt as percentage of GDP (updated 29-01-2015)

Why? Because cutting into spending slows down growth and keeps the economy in a stagnation trap. The resulting underemployment equilibrium puts a lot pressure on household revenues just as those same households are getting into debt. We are thus faced with a second paradox: in a stagnating economy, trying to use austerity to reduce public debt also translates into an increased burden of private debt.

Conversely, a credible and efficient economic stimulation policy grounded in strategic public investments, the maintenance — or possibly the expansion — of public spending, and the modernization of taxation so that it efficiently retains the necessary revenues to validate those expenses and investments (revenues which currently accrue as unproductive savings, notably in businesses) would have a huge impact on growth that would translate into an increase in both denominators, i.e. the GDP and the income of a majority of households. Our current government has decided against promoting such an economic policy, which would incidentally enable us to initiate an ecological shift.

To conclude: The price of austerity

When an economy is stuck in a stagnationist trajectory, choosing austerity is very costly. This cost — in lost economic growth, in weakened households burdened with debt, in under-equipped productive businesses, in uncreated quality jobs, and in disorganized public services — is not the temporary burden of a generation that has to tighten its belt for the sake of the future. Actually, austerity will leave permanent marks on our society. This is a cost with which Quebec’s economy will have to reckon for years to come. The longer we engage in this economic experiment, the longer the effects will last, and the more the inheritance left to future generations will be measly and poor.

The current government has led Quebecers into a vast and ambitious macro-economic experiment. Austerity has been chosen here as it was elsewhere in 2010 and since. Governments in Quebec have continued on the same track with more or less enthusiasm. However, the current government, seven years after the crisis and smack in the middle of economic stagnation, has chosen to radicalize and intensify policies which follow from this choice, with the macro-economic effect of considerably amplifying austerity’s impact. This will certainly result in important structural transformations.

The government’s avowed objective since it was elected last year has been the infamous repositioning of the state and its economy in Quebec society, a pet project of Treasury Board president Martin Coiteux. Making the state leaner, more scanty, evanescent and withdrawn; opening up our wide range of public services to the private sector; normalizing the size and amplitude of the public economy according to North American standards; “provincializing” the state of Quebec — to borrow Robert Laplante’s expression –; submitting the economy and society to the forces of the market, as is the wish of Jacques Daoust, minister of Economy, Innovation, and Exports — these are the goals Mr. Couillard’s Liberal government seeks to achieve by choosing austerity.

The choice of austerity is also opting to part with the values and principles that shaped the construction of Quebec society since the Quiet Revolution, thereby creating an important cultural shift. Such shifts are crucial junctures in a society’s history. The essence of our modernity demands that the political forces that bear responsibility for these shifts assume them fully and submit them to public debate. Unfortunately, I don’t think the social option behind the choice of austerity is entirely acknowledged publicly by the forces that govern us and are submitting us this experiment. Indeed, we keep on being told that we won’t experience any decrease in the quality of services that we expect from the state as a result of all these upheavals and changes, while the goal is precisely to reposition the state by closing down programs and trimming jobs in the state apparatus.

Like many of my colleagues at IRIS, in the last year I have been travelling all over Quebec to offer training sessions to those who are directly hit by this choice of austerity: workers in the public sector and in community organizations, and regional economic development agents. Disorganization, demobilization, and marginalization are the real social impacts of this economic experiment on the workplaces and communities I have had the chance to visit. These social costs are added to the economic costs of the choice that is austerity.

This article was written by Eric Pineault, a researcher with IRIS, a Montreal-based progressive think-tank.

Photo: feck_aRt_post/flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.