Reactions to the federal budget presented in March differed in Québec in comparison with the rest of the provinces. In this text we will first review the budget as whole before zooming into measures which caused a big uproar in Québec.

In its latest budget, the government brought to the fore an already existing manpower training measure and simply altered the way money is distributed. The apparent simplicity of this year’s budget, however, masks the failures of the government’s economic strategy in the past few years and raises doubts concerning new initiatives, particularly with respect to labour-sponsored funds and to investment in infrastructure.

Austerity: Major fail

The federal government has decided to stay on course in balancing the budget as early as the 2015–2016 fiscal year, when it even expects to accumulate a surplus. Finance Minister Flaherty has thus given in to the hardliners within the government by choosing not to delay for another year the elimination of the budget deficit. Even right-wing columnist Alain Dubuc called the decision “fairly ideological” in La Presse. It is hard to see what’s inciting the government to stick with its austerity agenda aside from electoral motives. Indeed, the consequences on economic growth are dire — leading to a dramatic decline in government revenue — and the global economic uncertainty seems like it should encourage a more cautious approach.

The deficit for 2013–2014 will thus reach $18.7 billion (1 per cent of GDP), which is $2 billion more than what was expected last fall and $8 billion more than expected in the projections of the 2012 budget. Despite these major setbacks in the fight against the deficit, the government believes it can reduce it by two thirds by the end of fiscal year 2014–2015, lowering the deficit to $6.6 billion, on the way to a balanced budget (and even a surplus) in 2015–2016. Such optimism is surprising given how badly so much austerity is affecting growth. According to the CCPA’s estimates, austerity measures will cut 0.8 per cent from GDP growth.

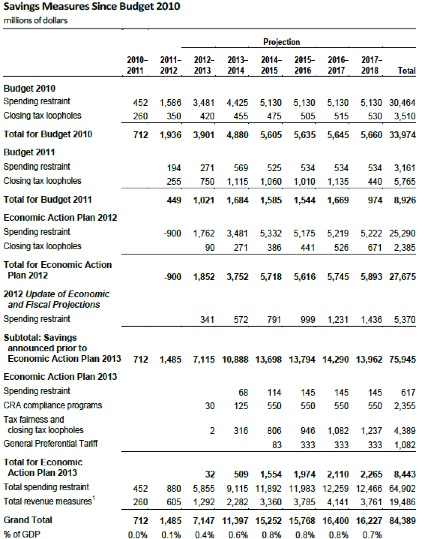

It is important to bear in mind that the federal government’s deficit-fighting strategy relies far more on spending cuts than on revenue increases. In fact, the budget offers a synthesis of the impressive cutbacks made in recent years and expected to exceed $16 billion in 2017–2018.

Compared to what is happening internationally, this relentless targeting of a zero deficit is even harder to understand. The government’s “Economic Action Plan 2013” (as the Budget is retitled) even goes so far as to state that “Canada’s fiscal position remains the envy of the world.” If that is the case, why is it necessary to shove an austerity pill down the throat of the Canadian economy, despite the failure with which the approach has met in economies throughout the Western world in recent years?

Transforming how job training is funded

The key, high-profile measure in this budget will have just about no budgetary impact in the short term. According to Ottawa, the training offered to Canada’s workforce is currently not consistent with the demands of the labour market. The former must thus be adjusted to meet the latter. In times of fiscal restraint, Ottawa plans to achieve this without pumping in any additional funds — and perhaps even by cutting back on the budget item.

The operation is fairly simple. The federal government gives the provinces a total of $500 million annually to support efforts to put people back to work. The provinces use these funds to pay for their job search assistance program: civil servants are paid to provide tools and advice to people who are looking for work. Provincial governments also pay for training which seems to match their profile. In Québec, Emploi-Québec seems to have been doing a good job in recent years in this respect, and some people even claim that unemployment has gone down because of its organizational practices.

The federal government now announces that 60 per cent of funds ($300 million) will now be used to finance the Canada Job Grant. This grant will be applied towards the cost of employee training (instead of paying civil servants’ wages), and it will only be paid if matching funding is provided by the provincial government and employers. An example is repeated throughout the budget documents. The federal government gives $5,000 to the provincial government to train a specific worker. The provincial level must then also provide $5,000 and the employer must also chip in another $5,000. When all these requirements are met, the worker can receive a $15,000 training. The remaining 40 per cent of funds ($200 million) will be kept for existing job search assistance programs.

Funding still reaches $500 million, but it must be used differently. A minor injection of funds ($60 million this year, $71 million in 2014–2015) will be used to help provide jobs for youth, disabled people, First nations, and recent immigrants. This new funding will seem pretty thin once it’s spread across the entire country.

The Canada Job Grant may seem interesting at first glance, but it raises a number of important questions.

First of all, will funds be invested in full? The requirements may prove to be quite a tall order to meet: both the province and the employer must provide matching funding. What happens if this condition is either never met, either not met often enough to enable the use of the entire amount currently being set aside by the federal government for this purpose?

Since the Québec government is also (hurriedly) fighting to overcome its deficit, it might not react enthusiastically to the idea of having to match Ottawa’s contribution in order to get funding. In the end, will there be more money for manpower training? It’s far from certain. Of course, the provincial governments could simply decide to reallocate the funds they are already investing in direct training in order to meet the federal requirements. But then, what would have been the use of the Canada Job Grant?

Second question which comes to mind: what will the money be used for? Let’s imagine a situation in which an executive says, “I want to hire this person, but he or she doesn’t have the necessary qualifications. However, I have people working in my company who can train him or her.” Could that company receive a combined $10,000 from the federal and provincial governments and invest $5,000 in wages for an already-hired employee who would be the ideal training provider? Answer according to the Ministry of Finance: probably. The Canada Job Grant therefore is a means of converting into direct grants to businesses funds that previously went to provincial governments to train workers, whilst at the same time forcing provincial governments to do the same.

Phasing out the labour-sponsored funds tax credit

The federal government has decided to eliminate its tax credit for labour-sponsored venture capital corporations. The budget states that “the phase-out of the tax credit aligns with the increase in venture capital investments resulting from the implementation of the $400-million Venture Capital Action Plan.” This means that a labour-sponsored funds tax credit is being eliminated in order to finance the venture capital strategy announced last year.

Although there is no data broken down by province available how this tax credit is used, the biggest players are all in Québec, as the Ministry itself admits. It is a known fact that these labour-sponsored funds have investment policies that are particularly favourable to local businesses.

So what are we replacing them with? A venture capital strategy that invests in “funds of funds” managed entirely by the private sector. Will a portion of these investments be made in Canada? The budget mentions nothing explicitly. In any case, the key thing is that this is a financial strategy, not an economic development strategy. People at the Ministry were very clear: the aim is performance, whether it comes from here or from abroad.

An infrastructure plan for… less infrastructure

At first glance, the Building Canada Plan seems to be another cornerstone in Flaherty’s eighth budget. Some observers had precisely expected the government to boost investments in infrastructure. As often happens in budget submissions, the funding announced (i.e. $53 billion), once deflated, reveals itself to represent in fact a reduction of $1 billion per year!

The lion’s share of these funds consists of investments that have already been announced. The only actual new fund, the New Building Canada Fund, consists of $14 billion in cumulated investments which, for the most part, will not be made until after 2020! The immediate spending — an annual expenditure of $210 million — replaces a fund that previously provided $1.25 billion annually. All in all, therefore, the government has announced a reduction in infrastructure investment, unless Canadians choose to re-elect the Harper government in 2015 and 2019.

This article was written by Guillaume Hébert and Simon Tremblay-Pepin, researchers with IRIS, a Montreal-based progressive think tank. Thanks to the Canadian Association of Professional Employees for the translation and to Marie Léger St-Jean for the edition.