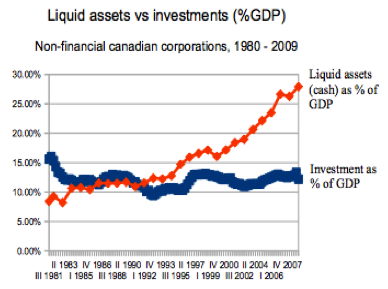

As we debate the merits and uses of a corporate tax cut, corporations themselves have already adapted to their new fiscal “competitive” environment (which as Jim Flaherty says, brands Canada as “business-friendly,” using the same methods as Iceland and Ireland might I add). As of 2009, non-financial corporations were stashing up to 28% of the GDP’s worth of cash in the form of bank deposits in Canadian dollars and foreign currencies, while their non-financial investments represented a mere 12% of GDP (StatsCan table: 380-0011). This hoarding of cash is up from an average 5% in the ’70s and 10% in the ’80s.

The following graph presents the relation between corporate investments as a per cent of GDP and corporate liquid asset holdings as a per cent of GDP from the early ’80s on. While investment and liquid asset levels were interrelated during the ’80s and ’90s, as of 2001 the relationship breaks down and corporations keep stashing ever-greater amounts of cash year after year. Now one argument for corporate tax breaks is to free up cash that can be used for investment purposes. Stephen Gordon has argued in the Globe’s “economy lab” that such a development could have happened during the last decade, pointing to the fact that investment in real terms has progressed from 2000 to 2007. And effectively the graphic below does capture this variation, investment from 2002 to 2007 progressed by whole 2 percentage points of GDP, from a trough in 2001. But looking over a thirty-year period we see that the cyclical dynamics of non-financial investment usually imply such and even greater variations over the business cycle. So much for a “tax effect.”

Looking at the data I don’t see cash-needy corporations in Canada; on the contrary, they don’t seem to know what to do with their money. Now another argument for lowering corporate taxes is that this will induce them to invest because their ROI will be higher. This argument comes up in the neoclassical “consensus” literature all the time. Now it’s hard to imagine any investment project that can’t beat the ROI of bank account interest income: 3% maybe 4% if you’re in very good terms with your banker!

A last argument is that actually you’re not taxing the corporation, but the people behind the corporate “veil” — its workers, consumers and shareholders, oh, and yes I forgot, its managers and high level executives (the very ones whose incomes are exploding and who are being paid in stock options for which corporations must make cash provisions in case these are “exercised”; oops I’ve somehow drifted form the main topic here). So where has the extra cash of previous tax breaks gone? Workers: well I don’t see significant real wage growth in Canada; consumers haven’t seen a crash in prices, shareholders, no significant fluctuation in dividend levels either. It all flies in the face of the facts, corporations are stashing cash, not spending. Still, what can we make of the case that taxing a corporation is taxing real people?

Here the neoclassical conception of the firm meets 19th century legal and juristic notions of the corporation as a mere organizational veil. Since then, the courts and the law here in Canada and in almost all advanced capitalist countries clearly and squarely decided that “corporations are people too. “And as people they accumulate for their own needs, not only for the needs of their “dependants.” Cash on hand is spending power, the power to appropriate wealth and social labour, and corporations spend not only to produce the goods and services that make our lives what they are, not only to make profits and generate dividends for their shareholders, but also to increase their power as organizations. Taxing corporate profits is, in a sense, limiting this power, and transferring it to the state, so that it can, ideally, be put to collective use.

One last issue must be dealt with concerning the Great Cash Stash. Is this a fundamental change in the way firms handle their cash flows and use their benefits or is this the effect of structural change in the Canadian economy where cash-saving firms have replaced spendthrift firms? Breaking down by sector the data, one finds the trend to be pretty much across the board: the whole of corporate Canada is stashing ever-larger amounts of cash. Leading the way is manufacturing, followed by oil and gas, construction, retail, wholesale, real estate, professional and scientific sectors. It’s interesting to note the different temporalities of this development though. The manufacturing sector has been progressively stashing more cash since the beginning of the nineties, while other sectors jump in after 2002.

So what to make of all this; how as economists can we explain the disconnect between corporate savings and investments on the one hand and the progressively delirious proportion of cash holdings?

A very unfashionable economist called Keynes once offered in his Treatise on Money a rationale for stashing cash in savings accounts: the cash is there in a liquid form ready to be used on the financial markets for speculative purposes. So maybe corporations are investing. I’m just not looking in the right place… Does stock jobbing and gambling on oil futures markets create jobs?

This article was first published in the Relentlessly Progressive Economics blog.