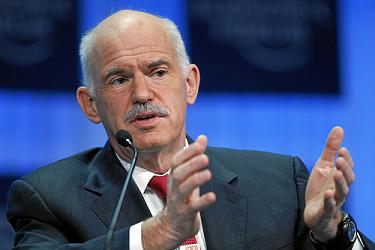

A year ago at about this time, I was in Athens attending a meeting of Socialist International. The president of SI, then and now, was George Papandreou, at the time also leader of PASOK and prime minister of Greece. I had the opportunity to meet with some of his key advisers (several of them ex-Torontonians) and listened closely when the prime minister addressed the meeting.

Papandreou was frank about Greece’s disastrous mistakes under governments of both left and right — including the fundamental error of deluding itself by issuing false statements about its finances and economy. He spoke about the brutal decisions his government felt driven to make to stave off national bankruptcy — decisions that his team acknowledged would reduce Greek living standards to where they were in the 1970s. He called for a fundamental review of the international banking and financial system, which now has more power over Greece than its parliament or its democracy. And he called on us, as fellow social democratic parties, to extend our solidarity and support to the people of Greece and to its government in the face of this overwhelming crisis, inherited from a feckless conservative predecessor.

I said as much in a column in this space, pecked out on my iPad from the floor of the meeting. A column, I must report, that went over badly with some of my political co-religionists. In their view, Papandreou was fundamentally wrong to attempt to work Greece out of its financial and economic crisis through austerity and debt refinancing, since the resulting depression would only further cut public revenue. All Papandreou was achieving, on this argument, was “kicking the problem down the road” (since the nation’s refinanced debt, plus much additional borrowing, would still have to be paid at some point); making Greece’s fiscal crisis worse by further suppressing its revenues; and further impoverishing his own people. My correspondents suggested, in summary, that Greece would do better to default on its public debt, to withdraw from the Euro, to devalue its currency and then, presumably, to rebuild its economy by revitalizing its exports (tourism, shipping trade, agricultural products, etc.) and reducing its imports.

It certainly proved to be true that Papandreou’s strategy could not hold. Greece went on to default on much of its debt. The details, agreed in March 2012, are here (see page 4 of the MOU). Greece imposed a nominal 53.5 per cent default on private-sector Greek bondholders. Some analysts calculated the real devaluation was closer to 75 per cent. Few tears were shed for the hedge funds who complained about these arrangements — they had snapped up Greek bonds at 35 to 40 per cent of their face value, and were hoping to be paid 100 per cent, plus interest. A bad bet, as it turned out.

Papandreou traded this “voluntary” debt relief for a new austerity program. That was a neat trick in the narrow world of public finance, on its own terms, since Greece escaped the consequences otherwise reserved for sovereign debt defaults — a global capital strike against further Greek debt issues; a wave of insurance payments to aggrieved debt-holders that would have tested the house of cards that is the international financial system; and, possibly, retaliation by Greece’s trading partners.

He then hoped to force a public debate in Greece over its real economic options by calling for a referendum on these arrangements. Papandreou’s partners, domestic and foreign, objected violently to this idea. And so, instead, the PASOK government fell. The prime minister resigned; his successors were defeated in an inconclusive election; the conservative opposition was elected in a second election; and PASOK is now a junior partner, outside of the cabinet, in a new conservative government committed to carrying out Papandreou’s agreements — if renegotiated, on terms proposed by PASOK to mitigate their recessionary effects.

What to make of it all?

Papandreou was right to tell the truth about Greek finances and its economy, and to look for ways deal decisively with them. He was wrong to accept bailouts conditioned solely on austerity, as his own party now acknowledges with their package of proposed renegotiations. Perhaps the European Union implicitly accepts this, since the proposed renegotiation has not been ruled out.

The PASOK government faced a bitter choice when it came to office: to keep the Ponzi scheme that were Greek finances going for a little longer; to cut a deal with the IMF and the EU at the price of an austerity agenda that, it turned out, the people of Greece would not accept; or to launch into rounds of default and devaluation that might, or might not, end at some point in a better place than the austerity agenda.

Perhaps the main point is this: It may not be in the power of a small southern European country to save itself from the fiscal and economic challenges stalking the western world. It may be that there were and are no tenable options for such a jurisdiction acting alone, and that the people of Greece must look to the EU, and the broader world, for answers and solutions to a world challenge. A challenge that is, emphatically, not about profligate public sectors, curable through further doses of poverty and inequality. Market failures led us to speculative bubbles in property markets, ill-conceived financial instruments, and misjudgements about public-sector debt issues. Private-sector banking systems were deregulated, and immediately threw prudence and judgment to the wind, financing those bubbles and runs in pursuit of quick bucks and fat bonuses. And then, when it all fell down, the same players persuaded governments to socialize their losses, helping themselves to the available public debt room. Now the bill is presented to the “little people” who pay their taxes and work for a living. And who are gently letting their governments know, at the ballot box and in the streets, that the bill is being presented to the wrong people.

We could afford to ignore this, when it was all about Greece. But as I write, the same storm clouds are beginning to gather around Spain and Italy. More dominoes are teetering — where will it stop? Prime Minister Stephen Harper foolishly believes that none of this is of any concern to Canada (far-away countries of which we know nothing, he presumably thinks). That kind of thinking has gotten the world, including Canada, into a great deal of unnecessary trouble before.

This article was first published in the Globe and Mail.