In a little noticed comment, Prime Minister Stephen Harper recently was reported to say:

“Dropping our tax rate has not caused the government’s corporate income tax revenues to fall, which indicates that it does in fact attract business.”

No one seems to have questioned his statement, even though it was made on the same day Canada dropped to 15th place on the World Economic Forum’s index of global competitiveness from 9th in 2009. These rankings show corporate tax rates bearing little relationship to measures of global competitiveness.

Harper’s statement puts him squarely in the company of the “Lafferites” and neo-conservatives who claim cuts to tax rates even at relatively low levels can pay for themselves by increasing economic activity and tax revenues.

The “Laffer curve” charts the relationship between tax rates and revenues. A tax rate of zero will obviously generate zero revenues while a rate of 100 per cent also won’t generate a lot of revenue either. Revenue-maximizing tax revenues are achieved at rates somewhere between these extremes.

While all economists acknowledge this relationship exists, there’s a lot of disagreement about where the revenue maximizing rate and how steep the curves are. Progressive economists tend to agree revenue-maximizing tax rates are higher, while some neo-conservatives claim tax cuts even at low rates will increase revenues

Early advocates of these type of tax cuts argued that lower tax rates would increase economic activity and thereby revenues. However, there’s little evidence changes in tax rates, except in more extreme cases, have a major impact on real economic activity.

Advocates of tax cuts also argue that cutting taxes can generate increased revenues from income and tax shifting. Individuals and companies can shift their income between jurisdictions or between different forms of income to take advantage of lower tax rates. The Prime Minister indicated this is what he thought happening when he said Canada’s lower tax rate was attracting business, no doubt with the recently announced takeover of Tim Horton’s and merger with Burger King on his mind.

So is it true: have tax cuts actually led to higher revenues? Can we keep our Timbits and eat them too?

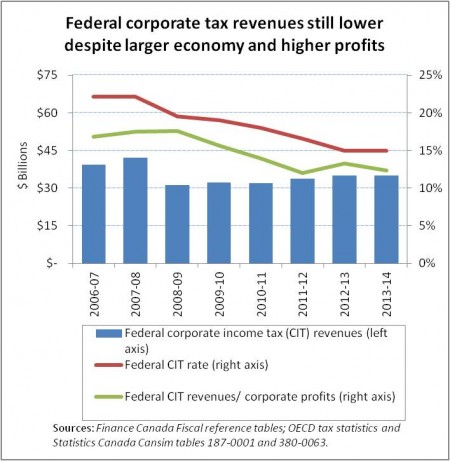

Contrary to what the Prime Minister said, federal corporate tax cuts have led to a significant fall in corporate tax revenues.

As the table above shows, federal corporate tax revenues rose to $35 billion in 2013/14, but this was still 17 percent below the $42.2 billion they were in 2007/8 when our economy and corporate profits were respectively 17 and 15 percent lower (in current dollars). In fact, as a share of our economy and of corporate profits, federal tax corporate tax revenues were 31 and 30 percent lower respectively last year than they were in 2007/8. That’s almost identical to the 32 percent cut in the federal corporate tax income rate from 22.1 per cent in 2007 down to 15 per cent from 2012 onwards (see table below).

Federal corporate tax revenues are expected to rise in coming years, but will remain well below the shares of corporate profits and the proportion of the economy they had been prior to these tax cuts.

If federal corporate tax revenues were at the same share of the economy and corporate profits as they had been just before the Harper government’s cuts, the federal government would have approximately $15 billion more in revenues. If they were at the same 21 percent share of corporate profits as they had averaged in the two decades before these cuts, the federal government would have about $25 billion more in corporate tax revenues annually. With these additional revenues, the federal deficit would have been eliminated last year and we’d have more money to fund public services.

As we have seen, there’s little credibility to the claim that corporate tax cuts are doing much to stimulate the economy with excess corporate cash at record levels and little growth in investment rates or the economy.

It’s more likely that corporate tax cuts have led to some income and tax shifting from other tax jurisdictions (such as the Tim Horton’s deal) or from personal income, which is taxed at a higher rate. These may have lessened the fall in Canada’s corporate tax revenue losses, but not by much. Even worse, this tax shifting makes the overall net impact even more negative as any revenue gains from income shifting come at the expense of even greater revenue losses elsewhere — and fuel a race to the bottom with tax cuts.

Few would dispute that corporate tax cuts increase corporate profits, elevate executive compensation and probably boost short-term shareholder returns. But to claim they pay for themselves by increasing revenues? That’s pure fiction.

As President Obama’s former chief economic adviser, Austan Goolsbee, concluded in his study of six decades of U.S. tax reform:

“The notion that governments could raise more money by cutting rates is, indeed, a glorious idea. It would permit a Pareto improvement of the most enjoyable kind. Unfortunately for all of us, the data from the historical record suggest that it is unlikely to be true at anything like today’s marginal tax rates. It seems that, for now at least, we will just have to keep paying for our tax cuts the old-fashioned way.”

And if corporations pay a lower share of taxes, that means the rest of us will pay more — either through relatively higher taxes or cuts in funding for public services.