Temporary foreign workers seem to be top of mind for many this week. In a CBC news article posted, the CFIB claimed that temporary foreign workers have a better work ethic than their Canadian counterparts. And recently, CBC reported that McDonald’s has been bringing in temporary foreign workers to fill new vacancies.

At the same time, new research from the Metcalf Foundation points out that migrant worker recruitment is big business — for-profit companies are making big money matching migrant workers with precarious jobs.

Ontario’s labour market has gone through a dramatic change since the turn of the century. The use of temporary foreign workers in the province is no exception.

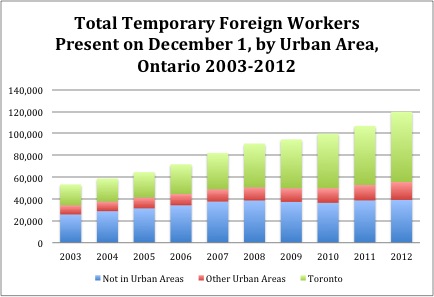

In 2003, there were about 53,000 temporary foreign workers in Ontario. By 2012, that number had more than doubled to 120,000 — a dramatic increase from 0.9 per cent of the province’s total work force in 2003 to 1.7 per cent in 2012. (Employment and Social Development Canada reports statistics on the number of temporary foreign workers present on December 1 of each year. Many TFWs come to Canada as seasonal agricultural workers and are approved to stay in Canada for no more than 8 months at a time. As a result, the statistics presented underestimate the total number of TFWs present in Canada in any given year.)

The number of temporary foreign workers in Toronto alone more than tripled between 2003 and 2012: rising from 19,000 to 64,000.

This is not just an urban phenomenon: the number of temporary foreign workers working in non-urban areas in Ontario has seen a 50 per cent increase (from 26,000 in 2003 to 39,000 in 2012).

Right about now you may be asking yourself: where are Ontario’s temporary foreign workers finding work?

For a variety of reasons it’s difficult to paint a comprehensive picture of the type of work being done by temporary foreign workers in a particular region or province, but some trends are worth noting. (Employment and Social Development Canada reports the number of labour market opinions approved each year by region. Citizenship and Immigration Canada reports the number of TFWs in the Country, Province/Territory and urban area on Dec. 1 of each year. But the two are not directly comparable “[b]ecause not all temporary foreign workers (TFWs) require a labour market opinion (LMO) to obtain a work permit.” Which means statistics contained in the Temporary Foreign Worker Program – Labour Market Opinion (LMO) Statistics cannot be interpreted as having a direct correlation with data published by CIC.”)

The available data reveal that use of the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) has increased substantially. If we assume that all seasonal agricultural workers are located in non-urban areas, then the increase in the number of seasonal agricultural workers is primarily responsible for the increase in temporary foreign workers outside of urban areas. They’re coming here in bigger numbers than before to work in fields and greenhouses, most often in southern Ontario.

From what we can tell, urban areas have a different story to tell.

Before 2002, the temporary foreign worker program was the domain of seasonal agriculture workers, live-in caregivers, as well as some short-term positions for highly skilled individuals. In 2002, in order to address short-term labour shortages, significant changes to the temporary foreign worker program expanded the type of eligible occupations. The new list included all low-skilled occupations (occupations coded as C and D on the National Occupations Classifications Matrix). Later, the program was expanded to include all occupations in all industries.

We also know that increases in the number of temporary foreign workers in Ontario filled between 8-9 per cent of all net new jobs in Ontario between 2005 and 2008. In 2009, even as Ontario lost more than 160,000 jobs, Toronto area employers brought in 3,000 more temporary foreign workers than the previous year.

Finally, in 2012 — a year when Ontario saw significantly lower job growth — Toronto area employers brought in more than 12,000 additional temporary foreign workers — filling a whopping 25 per cent of the net new jobs created in Ontario that year.

The temporary foreign worker program was created to operate as a complement to Canadian labour, not as a substitute. While the available data may not be definitive, high-profile news stories from across the country (including B.C., Alberta and Ontario) suggest that the opposite is true.

In response to criticism, the federal government has announced new rules, as well as fines and other penalties for employers who abuse the system — like those who bring in foreign workers under false pretenses or who fire Canadians in order to fill the position with a temporary foreign worker.

Ontario is currently facing persistently high unemployment, relentless long-term unemployment, high rates of involuntary part-time work and high levels of unemployment for new immigrants. Shoring up the temporary foreign worker program to protect against abuse and deter firms from using temporary foreign workers as a replacement for Canadians is a welcome move. Better data could also go a long way to ensuring that employers are not taking advantage of a program meant to act as a complement to Canadian labour, not a substitute.

Kaylie Tiessen is an economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario Office (CCPA Ontario). Follow her on Twitter @kaylietiessen.

For more information on Ontario’s labour market check out our recent report: Seismic Shift: Ontario’s Changing Labour Market.