The Fraser Institute’s annual Consumer Tax Index report generated some media buzz with its outlandish claims about just how much taxes have risen since 1961. Before you get worked up about this, consider that 1961 was over half a century ago, before the time of universal health care that we all benefit from, before the Canada Pension Plan and the Guaranteed Income Supplement that hugely reduced poverty for seniors, before the Canada Child Tax Benefit which is helping lower child poverty (though not enough!).

There are big problems with the Fraser Institute report’s methodology which lead them to grossly overestimate the tax bill of the average Canadian family.

The Fraser Institute misleadingly includes all business taxes, import duties and resource royalties in the tax bill of the average family. The argument that the average Canadian family pays for all business taxes is simply not convincing for two reasons. First, even if individuals ultimately pay all business taxes, it’s not necessarily Canadians that pay them (think of all the stuff we export). Second, business tax is paid largely by shareholders and only a small portion accrues to workers. Recent research from the U.S. pegs the split at 80/20. Given how unequally distributed shareholder profits and investment earnings are, taking an average of taxes paid by workers and shareholders is meaningless and grossly overestimates what average Canadian families pay.

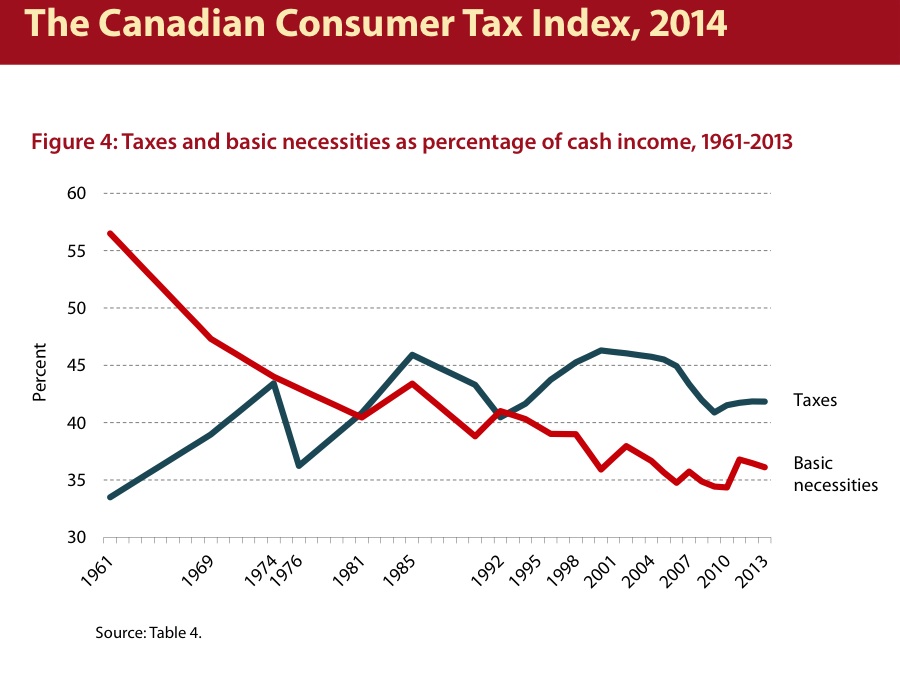

While the Fraser Institute report doesn’t tell us what a typical Canadian family actually pays in taxes, it gives a rough idea of trends in the total tax bill in Canada over the last 50 years. Business and personal taxes rose as a share of family income in the 1960s and then again between 1975 and 1985. But taxes have been cut significantly since 1999 (by about 5 per cent of income) and are lower than they were 30 years ago in the 1980s.

A more accurate measure of the total tax bill in Canada is the one used by the OECD, which compares total taxes collected with the size of the economy (as measured by GDP). The OECD numbers show very similar trends of increases in 1960s and 70s and significant decline since the late 1990s (about 5 per cent of GDP). For reference, Canada’s GDP was $1.82 trillion in 2012 and 5 per cent of that is $91 billion.

What neither of these charts tells us, however, is that the type of taxes Canadians pay have changed a lot, eroding the fairness of the system. Progressive taxes which ask higher income Canadians to pay higher rates (like the personal income tax) have shrunk as a share of the total tax bill while regressive taxes like the GST and other consumption taxes have gone up, taking up a higher share of incomes for lower-income households than from higher-income households.

What neither of these charts tells us, however, is that the type of taxes Canadians pay have changed a lot, eroding the fairness of the system. Progressive taxes which ask higher income Canadians to pay higher rates (like the personal income tax) have shrunk as a share of the total tax bill while regressive taxes like the GST and other consumption taxes have gone up, taking up a higher share of incomes for lower-income households than from higher-income households.

A comprehensive analysis of all taxes that Canadian families actually pay by my colleague Marc Lee shows clearly the erosion of tax fairness that accompanied the tax cuts of the early 2000s.

There has been two fundamental shifts in who pays taxes in Canada since the late 1990s:

- A shift of the tax bill from business to families (through large reductions of corporate income taxes and a proliferation of business subsidies and tax credits)

- A shift of the tax bill from higher-income to middle- and modest-income families (through personal income tax cuts at the high end and an increased reliance on regressive taxes)

The tax cuts introduced since 2000, visible in both the Fraser Institute and the OECD data, have disproportionately benefited Canada’s richest families. Now that’s something worth getting worked up about.