Every year when International Women’s Day rolls by, I can’t help but reflect on power, how it’s shared, and how women use the power they have. This year, I am struck by women’s power to reduce inequality, and not just to help ourselves. Women are key to reducing income inequality.

It’s been dubbed the girl effect, more powerful than the Internet, science, the government and even money.

Canada is actually a poster girl (sorry) for the truth that education and hard work can transform not just lives but societies.

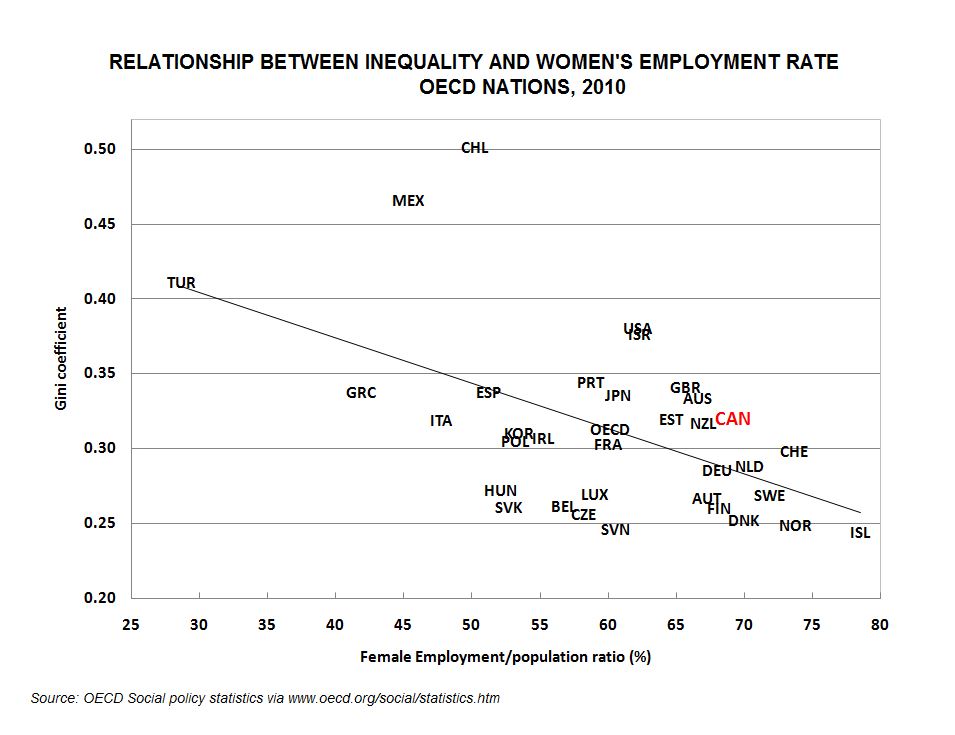

Look around the world and you’ll see a tight relationship between the level of income inequality in a nation and the proportion of women who work in the paid labour force, as the OECD chart above unequivocally shows. (For more, see here.)

There is no simple link between inequality and growth, but we know the more talent you can unleash and develop, the more you can change the course of a community and its history. Often hard times are what unlock doors.

Every recession is a “he-cession”: men lose more jobs than women in a downturn because the first thing to slow is the production in goods-producing industries that are typically male-dominated (mining, forestry, construction, manufacturing). Every early stage of recovery is a “she-covery”: men who lose $30 an hour jobs wince at accepting $15 an hour offers, but women grab them to make sure the bills get paid.

This is a story about women’s determination and effort, but it’s also a story about public policy.

Canadian women propped up the economy during the Second World War and in response to each recession thereafter.

Women’s share of the Canadian job market has climbed steadily, in response to economic calamity:

– 17 per cent in 1931

– 22 per cent in 1951

– 34 per cent in 1971

– 47 per cent in 1991

– 50 per cent in 2011

It’s just over 50 per cent today. We’re trailing men in self-employment, but that, too, is changing.

Women now play a bigger role in the paid labour force in Canada than in the United States, and we tend to get paid better than our American counterparts, helping us offset inequality more here than there. Why?

Possibly because we have wanted, and have been able to afford, more education (65 per cent of Canadian women over 25 have a post-secondary degree, compared with 40 per cent of U.S. women). Or maybe the fact that we have more communities that offer subsidized child care. We need way more affordable child care and post-secondary opportunities, but we have more access to these critical supports in Canada than the U.S..

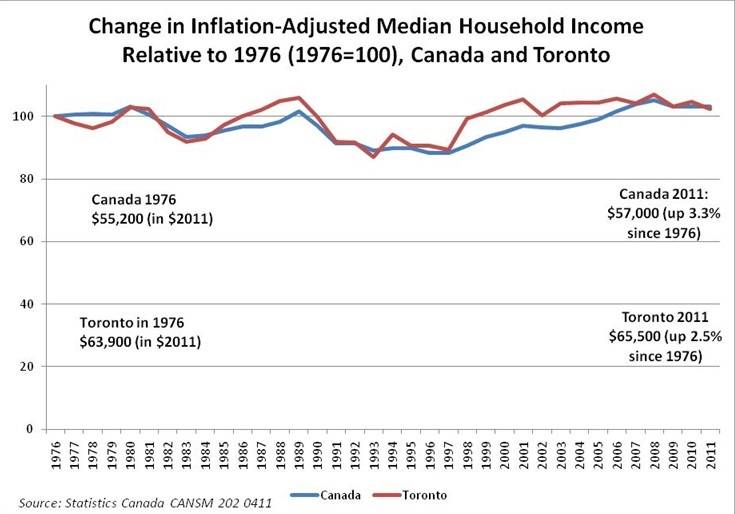

The trouble is, we’re pedalling faster to stay in the same place, and our strategies are running out of time. Median household incomes have barely held the line in the last 35 years — which is, sadly, a better trajectory than in the U.S. But “household incomes” now usually means two workers, not one; and this generation of workers is far more educated, as a cohort, than households in the 1970s.

The “work harder” nostrum has been taken seriously by Canadian women, who have warded off deeper inequality for the past 35 years. But it’s a time-limited option, not available for the next generation. Female employment rates increased by 40 per cent over the past 35 years. Among women of child-bearing years (25 to 44 years old) it went up a whopping 56 per cent.

It’s simply not mathematically possible to find the same boost in the coming years. Women are already working almost as much as men (see chart). There’s no “reserve army of labour” left in the kitchen.

We’re left with a basic equality: everyone only has 24 hours a day. How we use our allotment depends on how the market values our time and effort, and how public policy supports or plays against us.

Women have used their willpower and their staying power to improve the odds for themselves and their families. They’ve run out of time. So has the idea that Canada doesn’t have to worry about income inequality.

If the next generation is not to lose ground, businesses and governments are going to have to do more heavy lifting too. It’s not just women’s work.

International Women’s Day is a great day to think about these things. It shouldn’t be the only day.

Armine Yalnizyan is Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.

This piece was originally published at the Globe and Mail’s online Report on Business feature, Economy Lab.