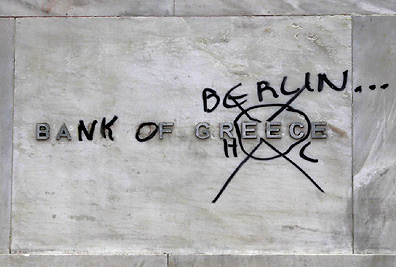

On Sunday, February 12, 2012, the people of Greece, in demonstrations and street fights all over the country, expressed in a massive, collective and heroic way, their anger against the terms of the new loan agreement dictated by the EU-ECB-IMF “troika” (European Union, European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund). Workers, youth and students filled the streets with rage, defying the extreme aggression by police forces, setting another example of struggle and solidarity.

Greece is becoming the test site for an extreme case of neo-liberal social engineering. The terms of the new bailout package from the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the so-called “troika,” equal a carpet bombing of whatever is left of collective social rights and represent an extreme attempt to bring wage levels and the workplace situation back to the 1960s.

Terms of the bailout

Under the terms of the new agreement, the following drastic changes are going to be put to vote:

– The minimum wage, which up to now was determined under the terms of the National Collective Contract signed by the Trade Union Confederation and the Employers Associations, is going to be reduced by 22 per cent. For new workers under 25, the reduction is going to reach 32 per cent. This is going to immediately affect around 25 per cent of the total workforce in Greece. Moreover, wage maturities (the increases in wages according to the years of workplace experience) are going to be frozen.

– This reduction is also going to affect all other private-sector employees covered by collective contracts and agreements. With most contracts having reached or reaching their end, with a new system of collective bargaining and mediation in place that openly favours employers, the terms of the new agreement also demand that individual terms of employment are going to change, leading in most sectors to wage reductions of up to 50 per cent (until now even when a collective agreement expired individual contracts signed under its terms could not be altered). These wage reductions are going to be devastating, taking into consideration that drastic reductions in public-sector pay have already been imposed and that labour cost in Greece is already down by 25 per cent, helped by unemployment having reached unseen-before levels (the official unemployment in November exceeded 20 per cent).

– All pensions are going to be reduced by more than 15 per cent, a reduction that is following other reductions that had been earlier imposed. Moreover, the terms of the agreement demand a new overhaul of the pension system paving the way for more reductions and raising of age limits. Pension reductions are not only going to affect the living conditions of older people but will also limit inter-generational solidarity, a crucial aspect of social cohesion in Greece.

– All forms of social spending are going to be drastically cut, including funds for hospitals and health coverage and social benefits. Since hospitals are already in critical condition because of earlier cuts, this new wave of cuts is expected to lead to a dramatic deterioration of health services in a country that is already facing deteriorating health indicators.

– A new wave of privatization is demanded, including the sale of crucial infrastructure such as airports and seaports and full privatization of public utilities.

– A new wave of lay-offs of public sector employees is going to be implemented, helped by a wave of closures of public institutions, including primary and secondary education schools, university departments and agencies such as the one responsible for public housing. Moreover, terms of employment in public utilities (partly owned by the state) and banks are going to change, with all provisions for secure employment eliminated, leading to another wave of mass lay-offs.

The social cost of this transformation is going to be immense. For the first time since WWII, large parts of Greek society are facing the danger of extreme pauperization. And the first signs are already there: increased homelessness, soup kitchens and a new wave of people emigrating from Greece in search of employment. And things are only going to get worse as traditional forms of solidarity, mainly through family relations, can no longer cope with the situation.

It is obvious that most of these measures have little or nothing to do with dealing with increased debt. Indeed, private-sector wage reductions are reducing pension contributions, leading to more deficits. What is at stake is an attempt from the part of the EU-IMF-ECB troika and the leading fractions of the Greek bourgeoisie to violently impose a social “regime change” in Greece.

Race to the bottom

According to the dominant narrative, the problem with Greece is a chronic lack of export competitiveness which demands a new approach based on cheap labour and doing away with any environmental restrictions, urban planning regulations and archaeological protections that could discourage potential investors. It aims to turn Greece into a big Special Economic Zone for investors. What is not mentioned in this narrative is that not only is the social cost going to be tremendous, but also that low labour cost competitiveness would lead to a hopeless “race to the bottom,” since there are always going to be countries, even in close vicinity such as Bulgaria, with lower wages. Moreover, it is a well-known fact that competitiveness does not rely solely on labour cost but is also based on productivity and this has to do with infrastructure, knowledge, collective experience and ability, exactly what is being dramatically eroded by the current economic and social situation in Greece.

What is missing from this narrative is the crisis of the Eurozone and of the whole European Integration project. It is becoming obvious that the problem is the euro, as a common currency in a region marked by great divergences in productivity and competitiveness. In a previous period, the euro functioned as a constant pressure for capitalist restructuring through competitive pressure, but at the same time it created increased imbalances, mainly to the benefit of European core countries such as Germany. In a period of capitalist crisis, the euro only makes things worse, increasing imbalances and deteriorating the sovereign debt crisis. That is why the crisis of the Eurozone is a crucial aspect of the current global capitalist crisis and one of the main failures of neo-liberalism.

Europe: Reactionary and authoritarian mutation

At the same time, the European Union is going through a reactionary and authoritarian mutation. This is the logic of the European Economic Governance, as inscribed in the proposed new fiscal Eurotreaty. According to this agreement, member states are going to include austerity measures such as balanced budgets in their national constitutions and European Union mechanisms will have the power to intervene and impose huge fines and funding cuts whenever they think that a member state is not prudent enough with its finances. And to this end, the “expertise” of the IMF in imposing austerity and privatization is also used. The prevailing logic is one of limited sovereignty and for this Greece is a testing ground. Already under the terms of the bailout packages by the EU-ECB-IMF troika, there are supervision mechanisms in place in all Greek government ministries, which dictate policies in an almost neo-colonial way. This is going to be the norm if the logic of European Economic Governance is imposed. That is why, although the current Greek government is acting in an almost servile way toward the EU, it is only receiving humiliating blows.

The European Union is rapidly becoming the most reactionary and undemocratic institution on the European continent since Nazism. Talking about a “democratic deficit” is not enough. What we are dealing with is an aggressive attempt towards a post-democratic condition, with limited sovereignty and accountability and little or no room for political debate and confrontation regarding economic policy choices, since these are to be dictated by markets through the mechanisms of EU supervision. Seeing ex-ECB central bankers becoming prime ministers, such as Mario Monti and Lucas Papademos, is more than symbolic.

But putting the blame only on the current aggressively neo-liberal and almost neo-colonial configuration of the EU is not enough. The most aggressive sectors of the Greek capital (banks, construction, tourism, shipping industry, energy) are openly supporting this strategy. Although sectors of capital have suffered from the prolonged recession, and despite the fact that the crisis has curtailed plans for a leading role in the Balkans, the dominant factions are investing in austerity, workplace despotism and doing away with all forms of workers’ rights as a means to regain profitability. However, the problem with this strategy is that an increase in exports cannot possibly compensate for the shrinking of domestic demand, which can affect even dominant sectors of capital.

The Papademos government has been trying to pass the terms of this devastating austerity package by ideologically blackmailing Greek society through the threat of default and exit from the Eurozone. But the question is not if Greece is going to default, but how. The measures imposed are simply leading to some form of creditor-led default — they have already taken the steps of debt restructuring and “haircut” of previous debt — with society taking the full cost.

Radical alternatives

That is why Greece defaulting on its own sovereign terms — that is, choosing the immediate stoppage of debt payments and of annulment of debt — is the only viable way to avoid social default. At the same time, it is also necessary to immediately exit the Eurozone. Stoppage of debt payments and reclaiming monetary sovereignty will help public spending on immediate social needs and will help stop the erosion of the productive base by imports. It is not a nationalist choice, as some tendencies of the Greek and European Left have argued, but the only way to fight the systemic violence of the current policies of the EU. Moreover, it is truly internationalist in the sense of the first step toward dismantling the aggressive neo-liberal monetary and political configuration of the EU, something which is obviously in the interest of the subaltern classes all over Europe.

Stoppage of debt payments and exiting the euro are not simple technical solutions. They must be part of a broader set of necessarily radical measures that must include the nationalization of banks and critical infrastructure, capital controls and income redistribution. But even these measures are not enough; what is needed is a radical alternative economic paradigm in a non-capitalist direction, that must be based on public ownership, new forms of democratic planning and workers’ control, alternative non-commercial distribution networks, and a collective effort towards regaining control of social productive capabilities.

Rethinking the possibility of such radical alternatives is not a simple intellectual exercise. It is also an urgent political exigency. Against the current ideological blackmail and the attempt by the government, the ruling classes and the EU to present extreme austerity as the only solution, what is needed is not just to say “no” to austerity but to bring back confidence in the possibility of alternatives. Hegemony in the last instance is about who has the ability to articulate a coherent discourse about how a country and a society is going to produce, cater to social needs, be organized and governed. The crisis of neo-liberal hegemony is indeed opening up a political and ideological space for the emergence of such a counter-hegemonic alternative, but it is not going to last for ever. Moreover, in the absence of a positive vision, the ruling classes are aiming at individualized desperation and sense of defeat as a means to maintain dominance. Rebuilding people’s confidence in the possibility of alternatives requires the collective work towards a radical program based upon the experiences emerging in the terrain of struggles. This is one of the most urgent challenges the Greek Left is facing.

Despite the fact that a coalition government of “national unity” under Papademos was practically imposed in November, the political crisis is far from over. PASOK, the Socialist Party, is facing its biggest crisis, the conservative New Democracy is facing increased pressure from its base not to accept the new measures, while the far-right have exited the coalition government. Twenty-two members of parliament from PASOK and 21 from New Democracy voted against the loan agreement and were subsequently expelled from their respective parties, marking a new phase in an open political crisis.

The extreme pressures from the troika, with the functionaries of the IMF such as Pool Thomsen acting as colonial governors, only makes things worse. Even though the agreement was passed through parliament, since the PASOK and New Democracy had a combined majority that could compensate for dissenting parliamentarians, the political system is being stressed to its limits. Attempts to create new political parties are underway, including an attempt toward a “Papademos” party that could gather all those supporting “regime change,” but they are far from gaining any momentum.

In such a setting, the Left is getting increased support, but at the same time is showing the limits of its strategy and program. SYRIZA (Coalition of the Radical Left) is still insisting in the fantasy of a democratic EU and refuses to bring forward demands such as exit from the euro. KKE, the Communist Party, despite its radical anti-capitalist and anti-EU positions, has sectarian tactics and underestimates the necessity for an immediate transitory program. ANTARSYA the anti-capitalist Left, has played an important role in the struggles and in articulating political goals such as the annulment of debt and exit from the euro, but does not have the necessary access to large layers of the subaltern classes. What is needed is radical re-composition of the Greek Left, both in the sense of the collective elaboration of a radical alternative that can create the possibility of counter-hegemony and of a radical Left Front that could represent the emerging new subaltern unity evident in mass demonstrations and strikes, in forms of self-organization, in networks of solidarity, and in collective experiences of struggle.

Currently Greece is entering a new phase of the protracted people’s war against the policies of the EU-ECB-IMF troika. The 48-hour general strike on February 10 and 11 and the mass demonstrations and street clashes on February 12 have become the new turning points in the struggle. The “people’s war” is far from over. Facing the danger of an extreme historical move backward, we refuse to despair. We insist on the “windows of opportunity” for social change that the current situation opens. We shall fight to the end.

Panagiotis Sotiris is an academic and activist who lives on the island of Crete, Greece. This article was first published in The Bullet.