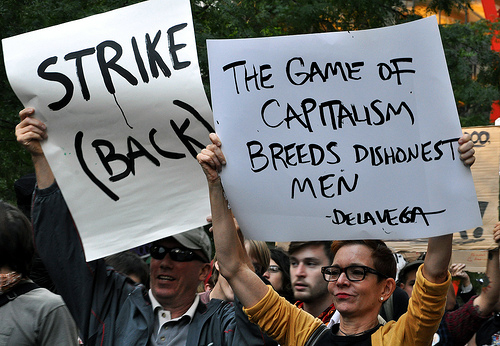

Occupy Wall Street and occupations around the U.S. and Canada are a radically new response to an old problem. The old problem is capitalism, a system that entitles wealthy minorities to direct economies for their private profit. What is radically new is seeing the alternative as the right of all to participate as equals in the decisions that affect their lives.

Capitalism entitles one per cent (perhaps as little as 0.1 per cent or as much as two per cent) to direct economic activity in their private interests. This one per cent includes major shareholders and top executives who control corporations, the system’s dominant institutions. Deemed in law to be individuals, corporations are actually capitalist collectives that combine the wealth of numerous shareholders with the aim of dominating markets. The largest control more revenues than most governments. Corporations and the one per cent that control them have the wealth to outspend everyone else in electoral campaigns. They control the media. Corporate lobbyists have a grossly disproportionate influence on governments and the agencies that are supposed to regulate corporate activity.

Capitalist competition to maximize profits pushes corporations to relentlessly expand production and to introduce labour-saving machinery, to speed up work, cut wages, and move employment to places where labour is cheaper. As production capacity expands, the share of income appropriated as profits rises while income from wages and salaries declines. Markets for consumer goods stagnate. Capitalists turn away from productive investment to speculation. Paper booms are followed by crashes.

Capitalism responds to rising poverty and chronic unemployment with repression, militarism, and war. Within countries, the marginalized, the dispossessed, and the disaffected are racialized and demonized as criminals. Globally, people who dare to take up arms against the system are demonized as terrorists. People in invaded countries are bombed, impoverished and turned into refugees. In invading countries, war glorifies the machismo that encourages the subjugation, abuse, and marginalization of women. It provokes violent divisions and hostility to others. But wars divert attention from worsening domestic problems. Billions in profits are made by the shareholders of politically well-connected military contractors.

The priority capitalism gives to short-term profit is at the root of growing environmental crises. Carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels are disrupting weather patterns, melting glaciers and polar ice caps, and acidifying oceans. Still, major transnational corporations continue to fund campaigns of denial. When they concede the seriousness of carbon emissions, corporate oligarchs propose profit-making schemes (scams) like cap and trade, or they insist that consumers are to blame and should pay. Here in B.C., corporate business happily supported the Campbell government’s carbon tax — paid by final users of gasoline and heating oil. Meanwhile, the government increased tax breaks and write offs for oil and gas exploration and development.

A 99 per cent solution

The 99 percent with little or no capitalist entitlement includes the self-employed — shopkeepers, owner-operators, farmers, and self-employed professionals — as well as most artists, artisans, full-time parents, pensioners, students, the unemployed, and those unable to work. Most — 85 per cent of population — rely on wages and salary work. None have a right to a vote in the direction of their labour time. As a condition of employment wage and salary workers are required to submit to master-servant relations.

The alternative is social ownership, equal human entitlement, and workplace democracy. With social ownership, towns, neighbourhoods, cities, regions, nations, and perhaps international communities will own means of livelihood that require cooperative labour. With equal human entitlement, residents of owning communities will replace shareholders as the legal beneficiaries of means of livelihood. With workplace democracy, workers in all occupations — transportation workers, sales people, professionals, factory workers, managers, daycare workers, service providers, teachers, accountants, nurses, and doctors — will democratically direct their labour time. General assemblies of all workers in an enterprise may elect managers; owning communities will elect or appoint auditors and perhaps directors.

With social ownership, higher profits would no longer trump human well-being. Communities will expect enterprises to generate sufficient revenues to cover costs, but will focus on providing acceptable employment opportunities for all available labour. They will plan to balance the financial costs of social services with revenues generated in exchange, and to balance the costs of imports with exports. When all inhabitants including people whose livelihood depends on tourism and organic agriculture, berry and mushroom pickers, scientists, educators, parents, and students as well as manufacturing and resource workers have a voice and equal vote in economic decisions, communities will limit industrial activity to the carrying capacity of environments.

Ending capitalism does not necessarily mean ending market exchange. Self-employment will be actively encouraged and supported. A greater proportion of goods and services are likely to be provided as social entitlements, but access to supplies and markets will remain a major source of material well-being. The right of individuals and communities to freely exchange goods and services with others — subject to democratically agreed regulations and taxes — will remain a basic human right. Perhaps when capitalist entitlement has become a distant memory, exchange values and markets will be anachronisms. Until then, communities from the local to the international will aim to base trade on the exchange of equivalents in human labour time.

From gross production to human well-being

In an ideal world, the overwhelming majority who work for wages and salaries would occupy their workplaces and begin working for their communities rather than for the profits of capital. In the real world, majorities are not actively opposing capitalism.

We can prepare for an alternative of human solidarity, equality, and democracy by mobilizing in communities, organizing in workplaces, and participating in political action for changes and reforms that are intended to reduce capitalist power and strengthen democratic human entitlement. We don’t have to agree on our particular priorities before we act.

Campaigning for steeply graduated income taxes is a place to start. In Canada and the U.S., rates of 75 per cent or higher on incomes over $250,000 could increase government revenues by five per cent or more of total national income. Government deficits could be eliminated. Funding for public health care, education, transit, and child care would be provided. Taxes on financial transactions would reduce speculation and raise more public revenues. Public ownership of banks, utilities, transportation and communications systems, and natural resources would weaken the power of capital and strengthen democratic control of means of livelihood.

Local communities can take initiatives to set up co-operatives and community-owned financial institutions, social housing, electrical power and communications utilities. Local food production can make people less dependent on the vagaries of capitalist markets. So can the expansion of social entitlements for health care, education, housing, child care, and basic income.

Environmental action can help ensure a better human future. Local, national, and international mobilizations can help reduce dependence on fossil fuel and replace automobiles with public transit and bicycles. Cities can be reconfigured so that walking once again is a pleasant, healthy mode of daily transportation.

Community and workplace mobilizations in solidarity with First Nations, racialized minorities, the marginalized, women, and immigrants will build human bonds and help expose the mean-spirited divisiveness of wealthholders’ privilege. Supporting efforts of poorer countries to meet their wants and needs can reduce disparities and build global solidarity.

Mass opposition to capitalism may begin with the unemployed, marginalized, dispossessed minorities, immigrants, or students. As it develops, unions will have critical roles. Unions give wage and salary workers a means to formulate their common interests independent of capital. Growing opposition to capitalism will inspire more workers to challenge unilateral capitalist control of means of livelihood through collective bargaining. Revived unionism will convince more people that a working-class alternative is practical.

Reforming political campaign financing and lobbying regulations can limit the control the one per cent now have over political agendas. Winning police to the side of democracy can reduce the capacity of the ruling class to use state power in its narrow interests. This can be accomplished if opposition to police assaults on the politically disaffected and mass mobilizations for transparent public accountability of the criminal justice system is accompanied by explicit support for the work police do in protecting persons and property. Supporting soldiers in the sacrifices they make while opposing militarism and war can expose capitalist profiteering at the expense of soldiers as well as of people abroad.

Recent mass protests in Egypt, Tunisia, Wisconsin, Greece, and Israel as well as current North American occupations show that people are willing to rally against injustice, militarism, unemployment, cuts to social programs, and rising costs for food and housing. Past experience indicates that mass protests can turn into general strikes and workplace occupations as well as into legislated reforms that strengthen democratic rights and human entitlement.

Allan Engler is a long-time Vancouver trade unionist and social activist. He is author of Apostles of Greed, capitalism and the myth of the individual in the market (Fernwood, Pluto, 1995); and Economic Democracy, the working-class alternative to capitalism ( Fernwood, 2010).