Both main parties in this election campaign are accusing the other of being big spenders. The BC Liberals claim the BC NDP is making election promises that are too expensive and argue the 1990s (the last time the NDP was in government) was a time of particularly high spending. The BC NDP points out that the provincial debt has grown significantly since the BC Liberals came to power in 2001.

But is too much of the public debate around this election focused on reducing the size of government?

The message to British Columbians from the BC Liberals’ campaign seems to be that an active government is the enemy of a healthy economy, and that the best way to tell if a government is doing a good job is to look at how much they are spending (the less, the better). This cannot be further from the truth. A strong, well-resourced government is not in contradiction with a healthy economy. In fact it is often government spending, including on staff to create and enforce appropriate regulation, that creates the conditions for businesses and communities to thrive.

Governments fund and maintain the transportation and energy infrastructure essential for business, they enforce contracts through the justice system, educate and train a large potential workforce and keep it healthy, set fair rules of the game, protecting honest business from unscrupulous competition, and the list goes on.

And often it is government itself that creates good family-supporting jobs, either though employing people directly in public services, through commissioning and building infrastructure, or via Crown corporations. The for-profit business sector doesn’t have a monopoly on creating wealth or jobs: the public sector, Crown corporations, non-profits and the cooperative sector all contribute significantly to our economy.

The paradox of thrift

If the global financial crisis of 2008 taught us anything, it’s that too little regulation is damaging for our economy and that government investment can play a key role in getting a slow economy going (remember the stimulus). When consumers and businesses are hunkering down and not spending, government must step in and invest. Otherwise, resources stay idle, unemployment grows and the economy moves to an even bigger slump.

Economists call this the paradox of thrift, the idea that while making cuts in lean times to “live within your means” makes sense for individual businesses and families, when everybody does it the result is a self-reinforcing economic slowdown and stagnation (due to a drop in aggregate demand). Investment is central to the functioning of the economy, and when consumers are not spending and business isn’t investing, despite sitting on large amounts of cash, it’s the job of a good government to pick up the slack.

The biggest economic problem facing B.C. faces at the present time isn’t the deficit, our debt levels (which are manageable), or excessive government spending and regulation. Our biggest problem is our stagnating family incomes, driving up already high levels of household debt, combined with a weak housing sector and slow business investment, which keep the unemployment levels relatively high.

Tracking B.C.’s spending

It’s no coincidence that one of the largest investments currently underway in B.C. is the $8 billion ship-building contract from the federal government (yes, a public expenditure). The economic benefits of this contract for B.C. are estimated to far outweigh the impact of the 2010 Winter Olympics, another economic boost for the province brought to you by government spending.

It’s in this context that our political parties are accusing each other of being big spenders. The numbers, however, show no evidence of government “overspending.”

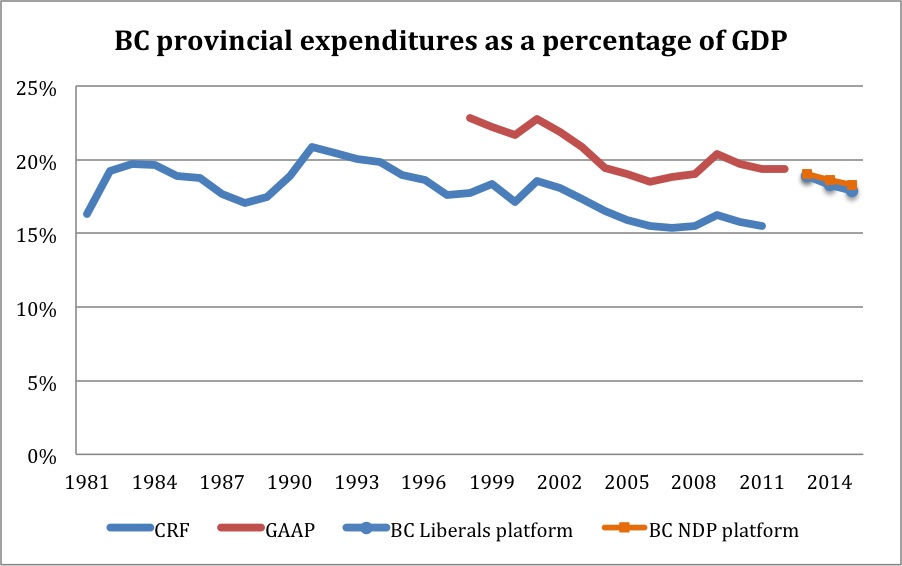

Contrary to the popular rhetoric, the BC NDP government of the 1990s largely followed the national trend of government spending cuts, as shown in the chart above. This chart tracks B.C. government spending from the early 1980s to the present, and then adds two short lines capturing the spending plans contained in both the BC Liberals and the BC NDP platforms.

When measured as a share of the economy (or GDP), B.C. government spending under the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) declined in both the 1990s and the 2000s, and is now at levels significantly lower than in the 1980s. (The new B.C. government accounting system, based on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (or GAAP), introduced in the early 2000s shows essentially the same story, though the numbers for government spending are slightly higher because they include the net expenditure of school districts, universities, colleges and health organizations, known as the “SUCH” sector, and Crown corporations.)

Notably, the spending proposals of the NDP platform and the BC Liberals Platform (as outlined in the 2013 B.C. Budget) are strikingly similar when expressed as a share of GDP. Both represent a decline in the size of government as a share of the economy, though the BC Liberals are proposing a slightly larger decline.

The BC Liberals have made much of the NDP’s election spending platform being “unaffordable”, but the reality is that the $2 billion of extra spending proposed is over three years and only amounts to a 1.5 per cent increase over the spending plan outlined in the BC Liberal government’s February Budget. A 1.5 per cent increase is hardly something to write home about, much less to make billboards of. In fact, the two parties’ platform spending commitments are barely distinguishable in economic terms. Political posturing and advertising aside, the BC NDP is only proposing to increase government spending by a very modest 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2015.

There is, as you see, no evidence to support claims of government “overspending” at any point over the last 25 years. Our current fiscal crunch is the result of a revenue shortfall, caused by a decade of steep tax cuts followed by a global recession and a fragile, slow recovery. If anything, the slow economy demands bolder government investment than either government contender is prepared to put forward.

Spending protects what’s precious

But beyond the macroeconomic effects of government spending, what our government spends money on matters a lot. Back in the early 2000s, the B.C. government of Gordon Campbell argued that the best thing a government can do for the economy is cut taxes and simply get out of the way. A Ministry of Deregulation was created with the aim to reduce regulations by one third, as if these regulations were simply useless paperwork to make life difficult for citizens and businesses.

You know who has very limited employment standards regulation, lack of oversight and enforcement capabilities? Bangladesh, where a garment factory building recently collapsed, killing over 700 workers. And Texas, where a fertilizer plant explosion in mid-April killed 14 people, injured over 200, and damaged homes and schools in a large blast zone around it. And because the government of Texas does not require insurance for hazardous activities, the plant only held insurance of $1 million, vastly inadequate to compensate the town for the damage the explosion caused.

It’s the entirely preventable industrial disasters like the ones in Bangladesh and Texas that underscore the crucial role of government. In both cases, due to lack of oversight and enforcement on the part of the local governments, the companies were operating despite it being known that they were not following existing safety measures.

Lack of regulation, oversight and enforcement capabilities are not just an issue for workplace safety. Without sufficient public sector staff, resources and authority for this staff to do their job, we cannot protect our environment, responsibly steward our natural resources or take care of B.C.’s most vulnerable children. Deep cuts to the B.C. public service, documented in my recent CCPA report Reality Check on the Size of BC’s Public Sector, have compromised our government’s ability to do its job well.

Deep cuts that wound

Almost weekly now, there are media reports of the direct effects of public sector cuts.

– The Ombudsperson’s report on seniors care painted a picture of a system in crisis, where too many of our elders age and die without adequate supports and without dignity, clearly the result of underfunding and a failure to provide oversight and regulation.

– Child protection services are being repeatedly flagged as failing our most vulnerable children. Here again, gaps in services are directly linked with short-staffing and impossible workloads for MCFD social workers.

– We have a legal aid system in shambles, where an increasing number of marginalized people are having to represent themselves. Justice isn’t being served after funding for legal aid was cut by 40 per cent in 2002, and 45 legal aid offices across the province reduced to two regional legal aid centres.

– Employment standards in B.C. are not being enforced after the Employment Standards branch lost a third of its staff and half of its offices in 2002. The shift from a pro-active inspection system to an online self-help kit for reporting and resolving workplace standards violations led to a dramatic reduction in complaints being made, but few believe it made the system fairer.

– The Forest Service lost a quarter of its staff and half its district offices over the 2000s, undermining out ability to engage in forestry management and oversight.

Big picture reality-check

This is the true legacy of cuts in government spending and public sector jobs, and the inevitable flip side of over a decade of tax cuts. And these cuts have failed to deliver on their promises of job creation and shared prosperity.

What are B.C.’s political parties proposing to do about this should they win the election? The BC Liberals platform includes another core review of the public service in search of addition “savings,” otherwise known as more cuts. They continue to insist that resource extraction and export is the only way to create jobs, and that job creation is the only solution to poverty, glossing over the large low wage sector in B.C., which fails to pay a living wage.

The BC NDP platform reinvests marginally in the B.C. public service by hiring more teachers, education assistants, librarians and counselors in schools, more social workers to support vulnerable B.C. children in care, more home support workers to provide care for seniors, by proactively enforcing employment standards, and strengthening environmental review standards for resource projects in our province. But in all these areas, the planned reinvestment is very modest.

The big picture reality-check: neither the BC Liberals nor the BC NDP have a record of overspending, and neither have presented platforms that would change that.

This article was originally published in The Tyee.

Chart sources: BC Ministry of Finance, British Columbia Financial and Economic Review 2008 (Table A2.8) and 2012 (Tables A2.8, A2.14). BC Liberals Platform (same as BC Budget 2013), BC NDP Platform.