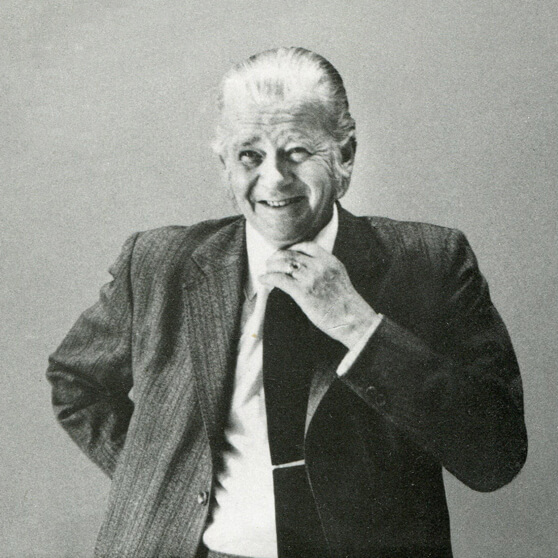

Fifty years ago, the economist E.F. “Fritz” Schumacher published Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. It went on to be listed among the 100 most influential books since WWII by The Times Literary Supplement, and even garnered Schumacher an invitation to the White House. This year, on its golden anniversary, many point out that the contrarian work of political economy is more relevant than ever.

Schumacher called for an end to the empty obsession with economic growth for growth’s sake, a reoriented focus on human (and humane) means and ends, the creation of more self-sufficient local economies, and the integration of a sustainable respect for nature into economics. Today, his influence is everywhere. It is no surprise that this year’s Schumacher Lecture was given by Kate Raworth: the mind behind the smash hit Donut Economics.

And yet, Schumacher penned the book just before the ravenous fire of neoliberalism consumed voraciously in the opposite direction. The Great Recession, COVID, record levels of natural disasters, and an inflation crisis have not since quelled it. The fact is: Small is Beautiful has captured many minds and hearts over the past century but lost most of the material battles.

Schumacher’s book is dangerous to the neoliberal status quo, but its focus on practice has always been downplayed while its sentiment has been lauded. That won’t do for the next half-century. In our system of fantastically lopsided ownership and wealth, it doesn’t much matter if most people merely agree neoliberalism is terrible, or that we need to take action on climate change, or that the wellbeing of real people needs to be placed above abstracted measures of economic growth. (Over 80 per cent of Canadians also support a wealth tax on the top one per cent; there is no wealth tax.) It won’t be until enough people start practicing the alternatives in real numbers that the illegitimacy of “giantism” will have to be properly addressed.

Schumacher himself was heavily engaged in practice at the time of his death. Were he here today, he would surely urge us to focus on the book’s call to action.

Remembering The Book That Questioned Everything

Small is Beautiful popularized a framework that shifted the pivotal question from: what’s good for the economy? to: what’s an economy for in the first place?

From this vantage point Schumacher offered a forceful contrarian voice to mid-twentieth industrial economics, be they capitalist, state socialist, or mixed in nature. In his view, all three had an unhealthy devotion to an empty goal: economic growth for growth’s sake. In fact, the term “standard of living” was measured by economists in terms of how much a country consumed. Towards the goal of maximum consumption, governments and corporations had come to worship what he called “giantism”—the belief that big is best—with big corporations, big machines, big militaries, big cities, big governments, big monoculture farms, big finance, etc.

Yet the wealthiest nations on a per capita basis tended to be small, not big. The cities with the happiest citizenry tended to be of manageable size while by the 1970’s the giant metropolis of New York was rife with poverty and going bankrupt. And if maximum consumption meant maximum well-being, how could Buddhist monks who didn’t even have bank accounts be among the happiest people on earth? (Future generations of psychologists like Martin Seligman would find that American wellbeing stayed stagnant for the next half century even as the economy tripled in size.) A consumption-based measure was simply not a measure of what made real human beings healthy, happy, and fulfilled.

Worst of all, the practices of giantism destroyed our environment. Schumacher died before climate change was a mainstream concern, but he recognized that fossil fuels were finite resources and saw the negative externalities that occurred when natural resources were destroyed. Like many Indigenous voices before him, he chastised economists who praised the decentralized intelligence of markets while sparing no thought to destroying billions of years of intelligence stored up in a complex ecosystem.

Schumacher argued that we needed to reverse our objectives. We needed what he called “a study of economics as if people mattered.” He proposed a “Buddhist economics” in which thinking economically meant producing the most wellbeing with the least destruction. Like the Buddhist monk who flourishes by taking care of the most personal resources, practices were genuinely economic when they applied care, intelligence, and creativity to sustainable resources to generate flourishing among living things.

Towards that end, we needed to chuck allegiance to giantism and ask: what scale is appropriate for the goals of living creatures? When it came to enterprise, workers were often most free to apply their intelligence and be more than a cog in the machine when working in smaller, local enterprises. Smaller companies also gave more room for experimental problem solving in which mistakes could be made without causing catastrophes. When it came to technology, some of the most practical was supplied by nature, like the Amazon rainforest acting as the lungs of the earth and tree-lined streets providing natural cooling systems. Machines of intermediate size, meanwhile, were less alienating and, being more affordable, easier to democratize the ownership of. Schumacher, who was especially hopeful this point would be taken up in poorer countries and neighborhoods, called this “technology with a human face.”

Sometimes larger companies were necessary, he admitted, but when that was the case we had to remove capitalist exploitation and look to “attain smallness within bigness.” That didn’t necessarily mean government ownership, but it did mean expanding employee-ownership, cooperative enterprise, democratic participation, and the integration of the larger community into the company’s benefits. In this more moderate, pluralistic, sometimes even conservative sense, Schumacher was a socialist.

This last point is an oft-neglected aspect of his work, and sometimes Schumacher has merely been invoked as a toothless celebration of small business. Schumacher, however, was perfectly and emphatically clear that we needed to move beyond the capitalist division of workers and owners if these principles were to be made sustainable, dedicating an entire chapter to the subject, detailing existing successful worker-owned companies, and stating bluntly:

“When we move from small-scale to medium-scale, the connection between ownership and work already becomes attenuated…In large-scale enterprise, private ownership is a fiction for the purpose of enabling functionless owners to live parasitically off the labor of others. It is not only unjust but also an irrational element which distorts all relationships within the enterprise.”

Since his death the Schumacher Centre for a New Economics has continued to collect and support cooperative ownership models of enterprise, land, and finance, like community land trusts, worker cooperatives, credit unions, community supported agriculture, and local currencies, all of which have been implemented with high rates of success. These well demonstrated and dispersed methods are the ones we must turn to and join today. As Marjorie Kelly says: “the democratic economy already exists.” It is outnumbered, certainly, but that is something we have great power to change.

The Book Today: Ending Armchair Activism

Small is Beautiful today should be read as an urgent invitation to move beyond the squabbles of armchair activism and lead change by example. In this age of corporate domination and social media polarization, Schumacher offers sage advice:

“The power of ordinary people, who today tend to feel utterly powerless, does not lie in starting new lines of action, but in placing their sympathy and support with minority groups which have already started.”

And there are plenty of examples of Schumacher’s principles applied productively, especially among the various kinds of cooperatives which have now logged a billion members around the world. Further, the recent expansion of Community Wealth Building—which connects public procurement (purchasing) to inclusively-owned local enterprises—has shown this work can be taken far and quickly. Notably, Cleveland deployed these methods to create successful eco-friendly worker cooperatives facilitating racial, climate, and economic justice, while Preston, England, applied them rigorously to become The Most Improved City in the United Kingdom.

But let’s bring action to even closer proximity. Perhaps the greatest virtue of Schumacher’s approach is it allows us to get going with alternatives this instant—and encourage others to join us along the way. While there are many examples one could turn to, I’ll list two of particular value to Canadians at the moment.

The first is our ability to move our banking to a local credit union. While corporate banks—especially Canada’s Big Five—are enormously extractive, up to their eyeballs in fraud, and are playing instrumental roles in the housing and climate crisis, credit unions are democratic financial cooperatives lending for local purposes. With credit unions virtually everywhere, individuals, groups, and entire communities (should we, say, wish to organize a Big Five exodus) can remove their banking from extractive corporate outlets and increase local cooperative lending power instead. There are many excellent credit unions in Canada, but one glowing case study of what’s possible is certainly found in Vancity. In addition to being a financial cooperative itself, Vancity Credit Union has helped produce over 3,000 units of affordable housing through its Affordable Housing Accelerator Program & Fund, including via housing cooperatives and community land trusts. It also puts 30 per cent of its net profits into its Shared Success program, funding cooperative, inclusive, and eco-friendly initiatives. In terrific Small is Beautiful form, it is one piece of the puzzle that generates several others.

A newer development with impressive steam is community bonds. Here the partnership between Tapestry Community Capital and the SolarShare Cooperative is an exemplary—and joinable—case. Community Bonds are investments specifically raising capital for cooperative and non-profit enterprises. Paid back to the investor over time, they allow the same money to be used over and over to grow these sectors. Since its inception in 2018, Tapestry Community Capital has raised over $100 million to produce 60 such enterprises across Canada. Most notably, they helped quickly raise millions of dollars for SolarShare Energy Cooperative, which has now completed 51 renewable energy projects while keeping the wealth they produce in the local community. SolarShare is open for further bond investments right now.

Small is Beautiful has many valuable lessons still to teach at 50. To realize its significance, however, we must not view it as an impotent curmudgeonly attitude towards industrialism or a vague hope for something kinder. It is no such thing. Schumacher’s points were decidedly actionable: it is high time we moved beyond the destructive inhumanity of corporate capitalism; we have practical and empowering outlets around us for doing so; we should find those who have made a good start, and jump in.

These points understood, we might not only right this wayward economic ship, but find some joy, appreciation, and companionship in the process.