Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Problems? Oh, the Trans-Pacific Partnership has a few! Read about them all in the new series The Trouble with the TPP.

The Trouble with the TPP series looks at how the TPP treats the interests of rights holders and users completely differently.

I noted in the discussion on Internet providers that the most telling provision comes at the very end, where the parties recognize the importance of taking into account the impacts on rights holders and Internet providers. Internet users and the general public do not merit a mention as their interests do not seem to count for the purposes of a notice-and-takedown system for copyright works on the Internet.

The absence of users in the Internet provider section is not an anomaly. Throughout the TPP IP chapter, there are two distinct approaches. Where rights holders interests are concerned, the requirements are typically mandatory (ie. “shall”). Where the issue involves user rights or access, the requirements are not requirements, but rather non-mandated provisions (ie. “may”).

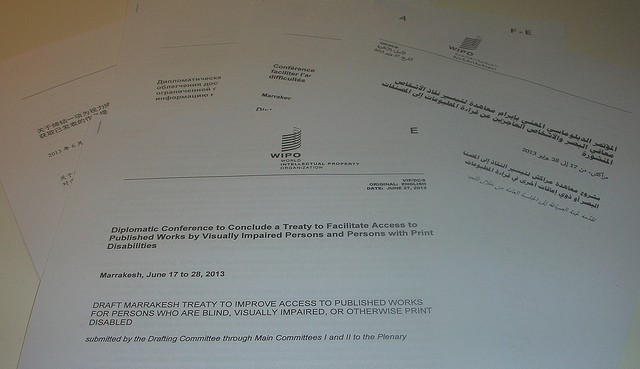

For example, consider the international IP treaty obligations in the TPP. Article 18.7 identifies nine international IP treaties and protocols that are all requirements for TPP members (Patent Cooperation Treaty, Paris Convention, Berne Convention, Madrid Protocol, Budapest Treaty, Singapore Treaty, UPOV 1991, WCT, and WPPT). What about the Marrakesh Treaty to facilitate access to published works for the blind and visually impaired? It is relegated to a footnote with no obligation to implement:

As recognised by the Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works for Persons Who Are Blind, Visually Impaired, or Otherwise Print Disabled, done at Marrakesh, June 27, 2013 (Marrakesh Treaty). The Parties recognise that some Parties facilitate the availability of works in accessible formats for beneficiaries beyond the requirements of the Marrakesh Treaty.

The TPP also contains dozens of obligations that guarantee rights holders everything from a longer copyright term to limitations on any limitations and exceptions. What about requiring balance within copyright? Article 18.66 falls back on “shall endeavour” language, meaning countries do not face a positive obligation for balance:

Each Party shall endeavour to achieve an appropriate balance in its copyright and related rights system, among other things by means of limitations or exceptions that are consistent with Article 18.65 (Limitations and Exceptions), including those for the digital environment, giving due consideration to legitimate purposes such as, but not limited to: criticism; comment; news reporting; teaching, scholarship, research, and other similar purposes; and facilitating access to published works for persons who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print disabled.

That this provision is regarded as a positive step forward highlights just how little user interests factor into the IP chapter. In fact, Jonathan Band notes that efforts to strengthen the balancing language during the Hawaii round of negotiations was “vehemently opposed by movie studios and other U.S. rights holders.” Negotiators ultimately caved to those pressures and retained the weaker language.

The weak language can similarly be found in safeguards against abuse of intellectual property rights. The TPP is filled with provisions aimed at guarding against misuse or infringement of IP rights. But what about when rights holders misuse their rights? Article 18.3(2) provides more weak language:

Appropriate measures, provided that they are consistent with the provisions of this Chapter, may be needed to prevent the abuse of intellectual property rights by right holders or the resort to practices which unreasonably restrain trade or adversely affect the international transfer of technology.

How about provisions to enhance access to the public domain? No such luck as Article 18.15 merely “recognizes” the importance of a rich and accessible public domain as well as the importance of publicly accessible databases to identify works that are now in the public domain. Or how about legal protection for libraries and educational institutions against criminal liability for circumventing a digital lock?

Unlike the many digital lock requirements in the TPP, Article 18.68 says that countries “may” provide that the criminal provisions do not apply to those institutions.

The examples go on and on with obligations when rights holder interests are involved and optional provisions for users. The public still has the option of being heard, however. As part of its consultation process, the Canadian government is inviting comments on the TPP at any time via email at [email protected].

This piece originally appeared on Michael Geist’s blog and is reprinted with permission.

Photo: flickr/ EIFL