Do we really have to talk about the Olympics for the next two weeks? You can change the conversation. Chip in to rabble’s donation drive today!

British Columbians no doubt feel thankful that the costs, security and other challenges facing the Sochi Winter Olympic Games far surpass what B.C. and Canada faced with the Vancouver-Whistler 2010 Games. But the 2010 Games were not without controversy and still raise the question of whether it was all worthwhile. Unfortunately, at least from a public policy perspective, that fundamental question was never properly addressed.

The B.C. government justified bidding for and ultimately hosting the Games on the basis of the economic impacts that they would generate. The government’s November 22, 2002 press release summarizing an economic impact analysis of the Vancouver/Whistler 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games was unequivocal and glowing.

“Combined with an expanded convention centre, the Games will mean up to $10 billion in total economic activity, more than 200,000 total jobs and $2.5 billion in tax revenues.

This is a once in a lifetime opportunity that will have a tremendous impact on [the tourism] industry.

We owe it to the future economic success of the province to throw our support 100 percent behind the Vancouver 2010 bid.

The Olympic bid is all about jobs, jobs and more jobs, with 10 to 12 years of economic growth.”

Press releases tend to simplify and exaggerate whatever the government wants to promote, and the government’s 2002 Games’ release was no exception. The impact estimates included the new convention centre even though the government argued for purposes of tallying up costs that the convention centre should be excluded — it stated that the convention centre wasn’t needed or dependent on the Games proceeding. Also, the estimates in the press release were based on a maximum potential tourism scenario — a scenario dependent on an aggressive marketing campaign that had not yet been developed and in fact never was.

In addition, the employment estimates in the press release were expressed as number of jobs when in fact the estimates in the study were of person years of employment (full-time employment for one year). The equivalent amount of on-going jobs over a ten-year impact period would be one-tenth the numbers reported in the release.

In any event, as we now know, the Games did not generate $10 billion in economic activity and hundreds of thousands of person years of employment. Nor did it have a tremendous impact on the tourism industry or significant impact on the economic success of the province.

Based on its analysis of what actually transpired, PriceWaterhouseCooper (PWC) reported that the total impact of the Games on gross domestic product (GDP) over the 2003-2010 period was $2.1 to $2.6 billion, over half of which was due to the operations of the Games itself. That averages about $300 million per year or one seventh of one per cent of B.C.’s GDP.

The incremental effect of construction activities on GDP was less than $1 billion, mainly because the construction projects were largely financed by government and effectively displaced spending in other areas. It is only the increase in spending in the economy relative to what would otherwise have taken place that increases total GDP and employment. Spending by government that requires either increased taxes or reductions in spending elsewhere only tends to change what is consumed and produced in the economy — not how much.

As for tourism, the incremental effect of the Games was minimal, contributing very little to GDP or employment. There were many reasons for this including the financial crisis of 2008, a strong Canadian dollar and what some suggest was a failed marketing campaign. Regardless, as compared to the pre-Games forecast of 40,000 to 56, 000 person years of tourism-related employment due to the Games (with the government of course touting the high end of that range), PWC estimated the total tourist industry impact at less than 10,000 person years of employment.

That the economic impacts from the 2010 Games were much less than the government’s pre-Games estimates should come as no surprise. Sports economist Andrew Zimbalist points out that estimated impacts of mega-sporting events on jobs and economic activity generally fail to recognize fully the displacement of spending and activity in other sectors. They also tend to ignore impacts on prices and profits captured by out-of-region interests which diminish local employment effects. (“Is it Worth It? Hosting the Olympic Games or Other Mega-sporting Events is an Honour Many Countries Aspire to — But why?”, Finance and Development, March 2010.

In his analysis of Olympic Games and similar events, J. Barclay concludes that “impact studies typically overestimate the gains and underestimate the costs”. Their main function, in his view, is simply to “provide the backdrop for overzealous campaigning and the acquisition of public money” (“Predicting the Costs and Benefits of Mega-Sporting Events: Misjudgment of Olympic Proportions”, Institute of Economic Affairs, June 2009).

There is little doubt that the government’s 2002 press release, with its misleading and exaggerated estimates of impact, was part of what Barclay called an “overzealous campaign” to commit public funds to the Olympics. The question that economists keep asking, though, is why?

Looking back on the Vancouver-Whistler Games, perhaps what is of greatest concern is not the exaggeration of economic impacts. That, as Zimbalist, Barclay and others point out, is commonly done. Rather, what is so troubling is that the government would have us rely on estimated economic impacts, whatever their validity, as a justification for undertaking such a major initiative.

The 2010 Games were not “all about jobs, jobs and more jobs”. What they were all about was a very concentrated and significant commitment of financial and human resources for the hosting of the event and the development of transportation, housing, sports venues and other infrastructure that was required or advanced for the Games.

There was never a full and proper forecast or accounting of the costs government incurred to host the 2010 Games. The provincial government originally stated it would spend no more than $600 million for the Games and later revised its stated commitment to $765 million because of increased security costs. But that number did not include a wide range of government and crown corporation expenditures due to the Games.

For example, much to the consternation of the province’s Auditor General, the province’s Games budget didn’t include the cost of the government’s own Olympics Secretariat created to plan, monitor and support the Games. It didn’t include the cost of Games-related marketing campaigns. It didn’t include the commitment of dollars and people by the province’s crown corporations, such as services provided by ICBC or the required refurbishment of B.C. Place by PAVCO. It didn’t include the cost of the major transportation and other infrastructure developed or advanced for the Games.

Nor, of course, did the province’s estimate of costs include expenditures that other levels of government would incur — expenditures that one way or the other taxpayers would be responsible for.

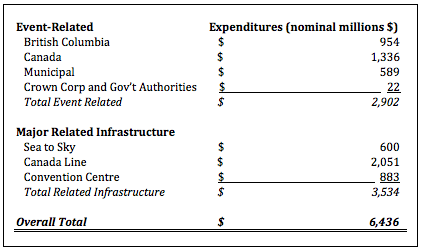

A review of federal, provincial and municipal reports by SFU grad Sean Calvert (jointly sponsored by CCPA and CUPE) suggests that government expenditures due to the Games totaled over $6.4 billion. This excludes all Vanoc costs covered by ticket, sponsorship and other Games’ revenues. It is the amount of resources government allocated to the Games and includes expenditures on sports venues; housing; legacy funds; support for First Nations; cultural events; “Own the Podium”; celebrations; ticket programs; pavilions; tourism marketing campaigns; hosting activities; security; medical services; insurance; transit; carbon offsets; and government Games-related planning and support. It also includes the cost of major infrastructure projects required or advanced for the Games.

Approximately $2.9 billion of the total government spending were directly required for or related to hosting the Games; $3.5 billion was for the major transportation (Sea-to-Sky highway and Canada Line) and other infrastructure (the new convention centre) that was developed or advanced for the Games.

There are limitations in the reported expenditure estimates, as some costs were not properly accounted for and some opportunity costs (such as the dedication of land and in some cases personnel) ignored. As well, the expenditure estimates do not net out the value of the assets they served to create. Nevertheless, the $6.4 billion does provide a reasonable (though likely understated) order of magnitude estimate of the amount of resources incurred or advanced by government as a result of the Games.

What is so troubling from a public policy perspective is that despite the magnitude of the government expenditures, the government never did any proper assessment of the broad public interest, and ignored independent attempts to do so, like the Multiple Account Benefit Cost Analysis of the 2010 Games that CCPA released in 2003. The government’s economic impact analysis certainly did not provide such an assessment. It is not just that these analyses typically overstate the impacts and ignore the costs. Most importantly, they simply do not address the critical public policy question: is the initiative and related commitments in the broad public interest — do the benefits exceed the costs?

A project is not good or bad depending on how many jobs it may generate. Its public worth depends on the value of the infrastructure or service the project provides and the costs that must be incurred for it. The employment impacts may offer some benefit, but that will depend on the nature, duration and location of the jobs; the potential supply of workers with the requisite skills; and the “incremental” income the jobs offer relative to what those hired could otherwise do. It is a complicated issue — one that economic impact studies seldom address.

There is no greater frustration for economists engaged in public policy analysis than the use and abuse of economic impact analyses to justify major public and private projects. That the big numbers the analyses generate are wrong and in any event largely irrelevant to the issue of whether a project is in the broad public interest is somehow lost.

The 2010 Games have clearly left a legacy of facilities and infrastructure. And for some the contribution to community spirit, sports and culture offered great value in itself. But the Games also entailed a very significant opportunity cost. The issue is whether the financial and other resources dedicated to the Games were put to their highest priority use.

Government resources are limited and public needs are great. The Games didn’t pay for themselves in any meaningful sense and they weren’t justified by the jobs they were said to create. Whether the allocation of in excess of $6 billion for the Games and related infrastructure was justified was never properly addressed. However, that is the economic question that should have been asked and debated, and is what other jurisdictions would do well to consider before they bid on future Olympics or other mega-sporting events.

Image: wikimedia commons