Yesterday’s 2014 B.C. budget contained very little news, as expected. Despite a significantly weaker economic picture for B.C. than what was projected in the June 2013 Budget Update, there are no new measures to help British Columbian families struggling with economic insecurity in the weak job market.

Five years after the recession officially ended, B.C. is facing a serious jobs problem. We actually lost jobs in 2013, and the share of working-age British Columbians in jobs (the employment rate) has barely budged since the lows of the recession. Simply put, the BC Jobs Plan failed to deliver sustained job growth in its first two and half years and there’s no sign that will change. Despite claims that tens of thousands of jobs would flow from LNG projects, B.C. Budget 2014 projects that the unemployment rate will increase from last year’s rate of 6.6 per cent and remain at 6.8 per cent until at least 2018. Essentially, Budget 2014 admits defeat on job creation.

Virtually all economic indicators for the next three years (2014 to 2016) have been revised down since last summer, including economic growth, personal income, corporate profits, consumer expenditures, residential investment, retail sales, employment and housing starts (see table 1.2). This means lower than expected government revenues. To get the books to balance, the government is cutting Ministry spending by a further $100 million since the Second Quarterly Report last fall. And while the number may not seem extreme, cuts add up after five consecutive post-recession budgets of belt-tightening.

Budget balance at whose expense?

In last year’s budget, when the government announced small increases in taxes for profitable corporations and very high earners (the top 2 per cent), the Minister of Finance was famously quoted: “We’re asking those who have more to pay a little more.” That was the right thing to do.

But now that the newly re-elected government has committed to both a 4-year tax freeze and balanced budgets, they’ll be turning to those who have less and asking them to pay more. That’s because all unexpected fiscal shocks will have to be absorbed by service cuts and/or increases in regressive user fees like MSP premiums, BC Hydro rates, etc. that hurt those among us who are least able to absorb the increases.

MSP premiums are going up by 4 per cent again as of January 2015, the sixth consecutive increase. This will effectively double MSP premiums since 2000, an increase much larger than inflation or the increases in healthcare spending. B.C. continues to collect as much revenue from MSP premiums as from corporate income taxes.

Balancing the budget in 2013/14 was a political not economic imperative. The price of the balanced budget is the missed opportunity to address some of the pressing economic and social challenges the province faces.

LNG tax framework

Revenues from the proposed LNG projects is not expected to materialize until 2017, and possibly much later (if at all).

There is not enough detail in this budget to assess whether or not the LNG fiscal framework will ensure British Columbians get a fair return on our publicly owned resources. It’s not clear when the money from LNG will start flowing in or how much funding the province is expecting to receive from the two-tier tax system.

If there isn’t much LNG tax revenue for the provincial government and if the jobs aren’t going to go to local unemployed British Columbians (and about 29 per cent of new jobs created in B.C. since the recession has been filled with temporary foreign workers), then what benefits are there for B.C. from extracting this non-renewable resource?

Budget fails to make strategic investments in a more sustainable economy

Budget 2014 projects a reduction in capital investment over the three-year budget horizon. This is surprising, considering the urgent need for rapid transit investment in Surrey and Vancouver, and the infrastructure deficits facing our municipalities.

There’s also little new investment in social infrastructure. There’s no support for B.C.’s many poor children and their families, for unemployed and underemployed youth, and for modest income families struggling with increasing housing and child-care costs.

Despite talk of skills training, there is little in this budget to fund improved accessibility and affordability of training programs. The budget for education is projected to increase by less than 1 per cent annually over the next three years. This fails to account for inflation and population growth and represent a cut in real terms. What is more worrisome, student spaces in public institutions in advanced education are projected to fall by 5,000 spaces over the next three years.

Health-care funding is projected to increase, but at much lower rates than what we’ve seen over the last 5 years (less than 3 per cent per year).

The problems that climate change poses continue to grow. We need an economic strategy what would invest in people and take bold steps to support a greener economy for our province, but Budget 2014 is silent on this.

There is no additional money for climate action, besides a very small amount for capital improvements in the public sector to reduce carbon emissions, funded from savings from dissolving the Pacific Carbon Trust. There are no additional subsidies for residential retrofits to make homes more efficient, a missed opportunity to create jobs and move us closer to meeting our greenhouse gas reduction goals.

The BC Early Childhood Tax Benefit, originally announced last year, does not kick in until 2015 and is too small an amount to make a real difference for families: the maximum benefit is $55 a month while childcare fees range can run upwards of $1,000 a month. This tax credit won’t make a dent in B.C.’s high child poverty rate, which is the highest in Canada.

There is some more money in the budget for social assistance, but it’s not much ($11 million over 3 years) so it’s not yet clear whether this will cover a much needed increase to welfare rates, which have been frozen since 2007.

New funding for social housing is welcome, but 100 units of new social housing per year for five years is barely a drop in the bucket. Our research suggests that B.C. needs 2,000 new units of social housing per year, 20 times more than what was funded.

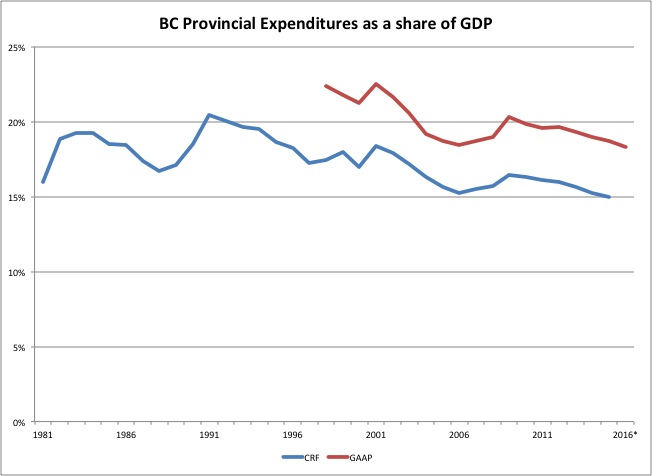

In fact, overall government spending is shrinking as a share of GDP and is projected to reach a record low level in 2017.

Sources: BC Ministry of Finance, British Columbia Financial and Economic Review 2008 (Table A2.8) and 2013 (Tables A2.8, A2.14). BC Budget 2014. CRF is the Consolidated Revenue Fund. GAAP is Generally Accepted Accounted Principles, a new accounting framework adopted in early 2000s, which includes next spending for school districts, universities, colleges and health organizations (the “SUCH” sector), and Crown corporations.

Years of tax cuts have left many of our key services underfunded and reduced our fiscal capacity. They have also made our tax system a lot less fair, shifting tax revenues from corporations to families and from upper-income families to middle- and modest- income ones (as we have shown here). Our taxes are too low, and there’s room to increase them without undermining our economy.

The other reason B.C.’s fiscal capacity has suffered is natural resource royalty revenues, which are significantly lower than they used to be pre-recession. It’s fair to wonder if B.C. is getting a fair return on our publicly owned resources. Revenue from natural gas in particular have been near record low, even as natural gas production is at an all-time high. Natural gas royalties are projected to increase starting next year, but we’ve seen large overestimates of natural gas revenues in the last few budget, so I’d take these forecasts with a grain of salt.

On the provincial debt

Our debt to GDP ratio is about 18.5 per cent and projected to fall over the next three years. Given the low interest rates, it’s a good time to invest. The debt-carrying costs are near record low levels.

It also matters what the borrowed money is spent on. Spending that enhances the future productivity of our province should be seen as a good investment. If debts are accumulated to invest in social infrastructure or in much needed transportation infrastructure, then they should be seen as good investments.

As it stands, B.C. has no forestry plan, no climate plan, no coherent infrastructure plan, no youth employment plan, no poverty reduction plan. Budget 2014 was a missed opportunity to build a province that shares our prosperity with all citizens.

Photo: BC Gov Photos/flickr