Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

The current federal elections offer Canadian voters, on the surface, parties with very similar economic platforms. In the end, all three main parties agree on the need for balancing the federal fiscal budget. Indeed, both the NDP and the Conservatives promise to balance the budget now or within the year, while the Liberals promise to balance it in three or four years from now. So on the grand macroeconomic plane of existence, all parties offer essentially the same vision.

Yet, the promise of balancing the federal budget now or later amounts to very bad economics, and will surely put Canada’s growth in jeopardy. Already our growth for this year, following a recession in the first part of the year, has been revised downward nuemrous times. For instance, the IMF has revised downward, yet again, Canada’s growth prospects for the next two years, and now some economists are confirming that we are settling into a period of what is called secular stagnation, that will amount to many more years of very low growth.

Canadians have many reasons to be worried.

Now, the act of balancing the government budget in and by itself may not necessarily be a bad thing,. For instance, if the budget happens to be balanced while we are at full empoyment with a high labour market participation rate, then so be it. In other words, the primary purpose of governments should be to pursue socially-beneficial policies like full employment and high growth. Balancing the budget becomes a distant and secondary purpose. This is the fundamental idea of what is called ‘functional finance’, which contrasts with the current conservatist view of sound finance, shared by both the Conservatives and the NDP parties who sees balancing the b udget as their top priority. Anyone who thinks that balancing the budget in the current economic conditions is not a ‘true leftist’.

However, in the current context of diminishing fiscal revenues, balanced budgets act like straight jackets by restraining the government’s ability to react to ongoing events, and some unforeseen ones. It is in this context that balanced budgets are equivalent to austerity. And there are all indications that this is the version that will prevail no matter which political party wins on October 19: all parties vow to balance the budget (now or over the next three years).

In a way, it should come to no surprise that all three political parties have adopted this fiscal conservatist approach. Conservatives have always advocated this (at least in theory), and the Liberals have made this their mantra for the past 2 decades, albeit to a lesser degree in this campaign. As for the NDP, they are following in the footsteps of other so-called progressive parties around the world espousing the values of fiscal conservatism in order to get elected.

Yet, in the real world, this practice has failed repeatedly, and repeatedly economists have warned against austerity during periods of re/depression. Even the IMF has changed its tune on this point. But political parties still don’t listen and continue on their merry austerity ways. As a result, the world economy is stagnating, and the current crisis in Europe is the inevitable result of such policies, which are proving increasingly destabilizing. Ironically, rather than reducing deficits, they often lead to increased deficits and debt.

And in Canada, since the 2007 crisis, our economic performance has been less than stellar, and ranks among the worst in the G20. There is no doubt this is the result of pursing austerity policies under the false pretense that they will somehow be expansionary.

In all of this, of course, we have forgotten what economics is all about. Economics is about the creation of wealth, not the single-minded pursuit of balancing budgets. Somehow, this was lost in translation. Now, it appears that unemployment, growth, poverty, and income distribution have become secondary problems. The first goal is to balance the budget, “come hell or high water”, as Paul Martin used to say.

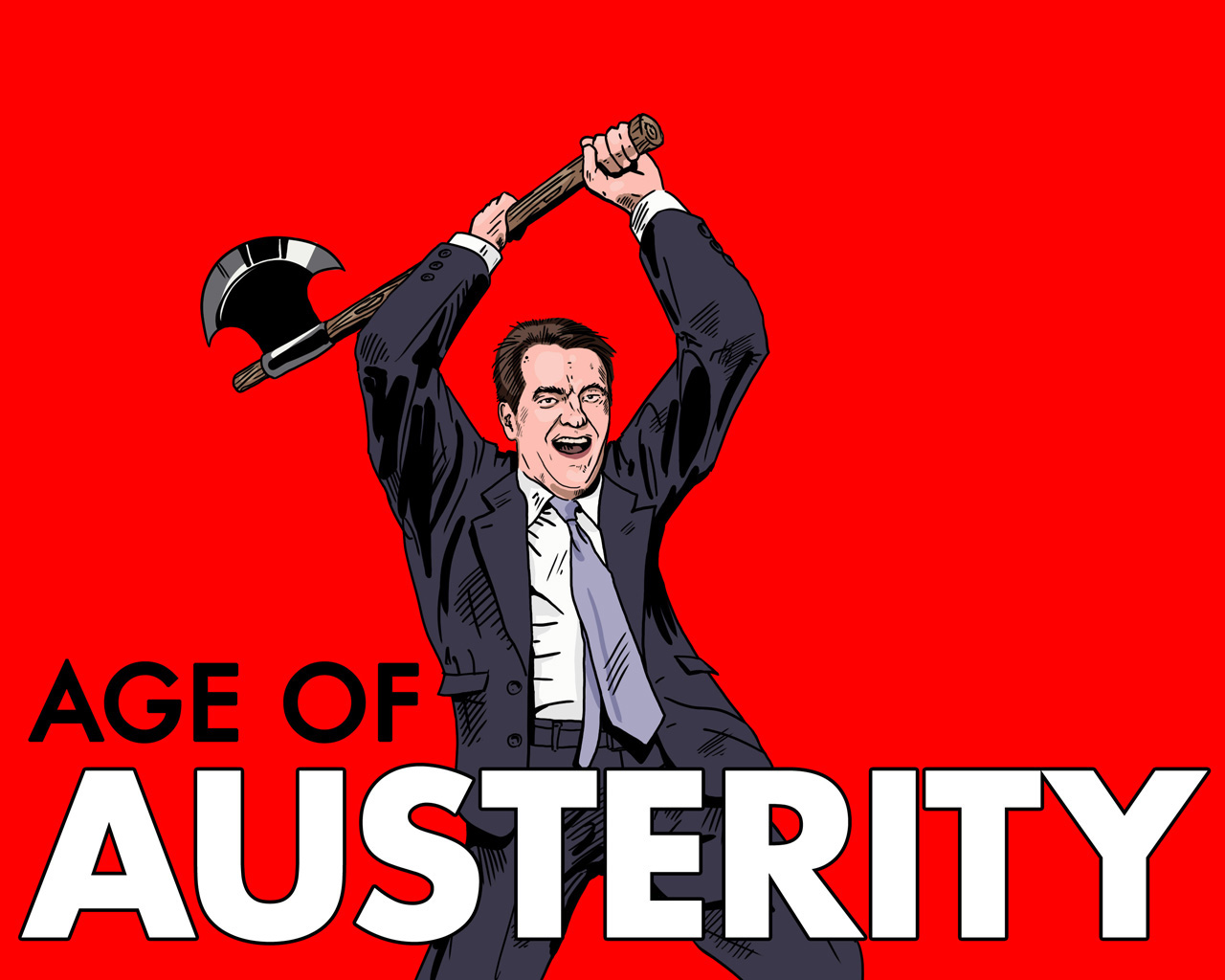

The repercussions will be severe. Our economies now risk settling into secular stagnation, that is anemic growth for the long foreseeable future. That will mean higher than normal unemployment and lower wage gains. Welcome to the age of austerity.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.