Women left Canada’s labour force in record numbers last year. Who are they and why did they leave?

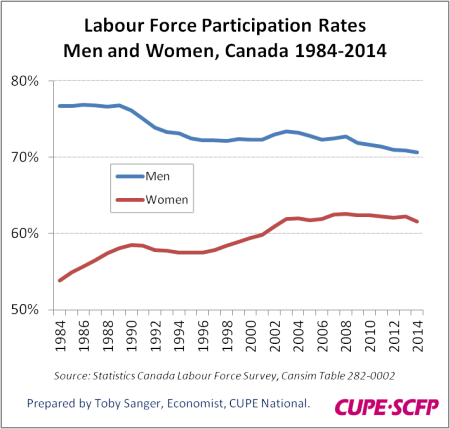

Over 80,000 women left Canada’s labour force in 2014, bringing their labour force participation rate down to 61.6 per cent from 62.2 per cent in 2013 (all figures annual averages). This is the lowest rate since 2002, and a reversal of decades of gradually growing gender equality through women’s participation in the workforce.

If women’s participation rates hadn’t declined in 2014, the unemployment rate for women unemployment rate would have risen from 6.4 to 7.3 per cent. This would have been the highest annual rate in 15 years and even higher than it was during the 2009-10 recession years. While there was a decline in women’s labour force participation immediately following the recession of the early 1990s, the decline last year comes five years after the recession was supposedly over.

The exodus is concerning for a number of reasons. Women, their household incomes and public revenues will all lose out from lower incomes. If women are leaving the labour force because of a lack of opportunities, inadequate pay or because they are overloaded with work and family responsibilities, it should also be a major concern.

Lower labour force participation will also put a damper on long-term growth of the economy, which is a reason Canada together with other G20 nations agreed last November to set a goal of narrowing the gender participation gap by 25 per cent by the year 2025. Just a few months into this commitment and Canada’s gap in women’s participation rates has widened rather than narrowed.

Part of the overall decline in participation rates is due to population aging: as a greater share of the population enters retirement age, participation rates naturally decline. But while this explains the drop in men’s participation, it doesn’t explain the greater drop for women. The biggest declines in workforce participation have been for middle-aged women aged 40-54. It’s also not a regional story. For the first year since at least 1977 participation rates for women dropped in every single province in Canada last year.

So what explains this exodus of women from the labour force?

It isn’t because women are retiring early because they can afford to on their own. Occupations with the greatest decline in female employment were clerical (-36,000); trades, transport, equipment operators and construction (-14,000); professional occupations in health such as nurses (-16,000); and middle management (13,000). Most of these aren’t higher paid occupations with early retirement benefits.

The industries with the biggest declines of women in their workforce in 2014 were manufacturing, trade, transport, finance and insurance, business and support services, and other and unclassified services. In total the female labour force declined by more than 80,000 in these industries, while the male labour force increased by an almost identical amount in these same industries. Employment trends in these industries follow a similar pattern.

The decline in women’s labour force participation wasn’t the result of an overall decline of employment in more female dominated industries, as some have suggested. On the contrary, labour force and employment levels of women in the most female dominated industries — education, health and social services and accommodation — all increased, while declining in the more heavily male-dominated industries. This means despite all the promotion of women in non-traditional occupations, Canada’s workforce became even more divided by sex last year.

Other explanations recently offered also come up short. While fertility rates have risen for older women, they’ve been more than offset by declining fertility rates for younger women, so this factor shouldn’t explain an overall decline in participation rates for all women. The rising share of landed immigrants with lower rates of labour force participation only explains about a tenth of the total decline in women’s labour force participation last year: participation rates declined at an equal rate for women born in Canada as for immigrant women.

Clearly we need to look elsewhere for explanations.

Countries with higher pay gaps for women also tend to have lower female participation rates. Higher child care costs and family caregiving demands for elders and other dependents also significantly reduce women’s labour force participation. More and more workers are also feeling overloaded: 60 per cent of respondents to a Globe and Mail survey reported feeling stressed and on edge at work.

There’s been very little progress in reducing pay gaps for women. In fact the gap has increased in recent years. The Harper government’s economic policies have focused heavily on male-dominated construction, resource-extraction and military-security industries and tended to emphasize more traditional family values. The lack of support for affordable child care and introduction of tax measures that increase incentives for women to stay home may also have an impact.

Together, these economic and social factors could be the reason why more women are leaving the labour force and staying home instead. And if these trends continue we should all be concerned, not just for this setback on the long march towards greater equality, but for the long-term health of our economy as well.

Update: Covered in the Toronto Star article by Sara Motjehedzadeh.