Until now, kindergarten to grade three classrooms in Manitoba have been limited to 20 students each. Yesterday the Pallister government announced they will remove the cap, and allow individual school boards to decide for themselves what is an acceptable classroom size.

This isn’t the first time this has become an issue in Canada. Class sizes have been at the centre of a struggle between the government and the teacher’s union since the early 2000s, culminating in a Supreme Court ruling not long ago.

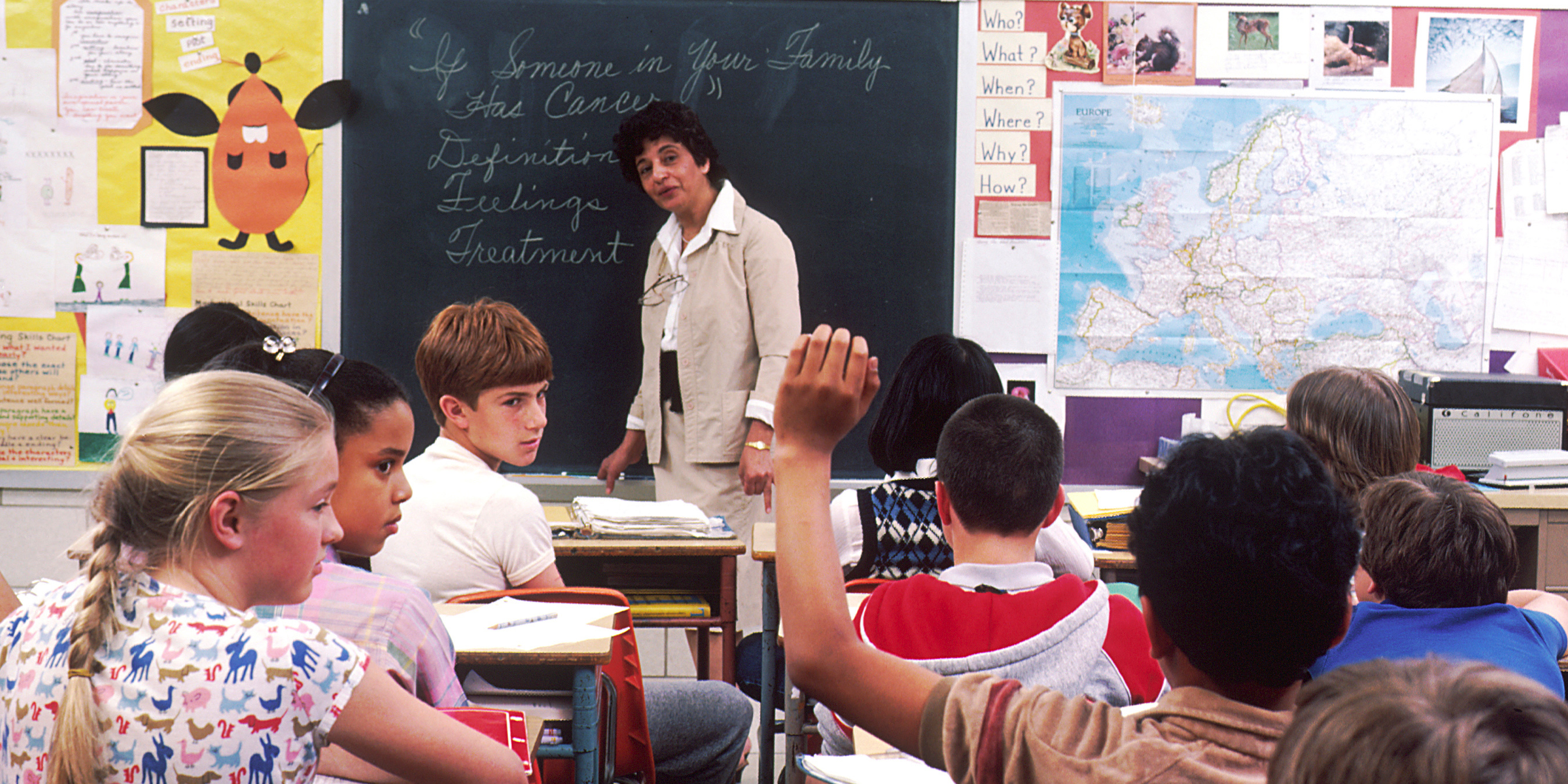

Larger classes are problematic. They make classroom management more difficult for teachers particularly by allowing them less time to spend with individual students and get to know them. It makes it harder for them to conflict between children and put a stop to bullying. More stress also means teachers likely aren’t performing at their best.

Larger classes hurt the quality of education for everyone, but especially for kids with learning disabilities.

I have nonverbal learning disorder (NLD or NVLD). In brief, NLD is either a developmental disorder or a learning disability, depending on which expert you ask. It is essentially a label for the fact that I have very strong verbal reasoning skills, but I face difficulty with other forms of communication. It doesn’t mean I can’t do them, but it’s much harder for me to understand visual-spacial and non-verbal communication. I also have some challenges with executive functioning. NLD is in some ways like autism and in some ways like ADD.

Typically of kids with NLD, I did great in school until about grade 4, and then I started to get increasingly frustrated with it. I did very well in some subjects and very poorly in others, which meant that to someone not looking very closely, it might have appeared that I was just lazy. Because I had poor non-verbal communication skills, I also had a lot of trouble picking up on social cues, which start to become important around age 9. This meant I lost friends and was severely bullied, to the point that I no friends in school in grade 5, 6 and 7 and I became suicidal.

My mom was the first person to notice that something was wrong. She could see I was frustrated and suffering, and she advocated for me at my school. She told me later that most of the teachers dismissed what she was saying. They told her that her expectations of me were too high because she was so highly educated, and that I was just an average student. My mom says she would have been okay with me being an average student if I had been happy, but she saw me suffering even though I hated talking about it.

My mom believes that what finally helped was that I happened to have the same teacher in grade 6 and grade 7. This meant that the teacher had more time to get to know me, and she started to believe what my mom was trying to tell her. With the teacher on board, the school referred me to a psychologist who diagnosed me with NLD.

The diagnosis was a huge relief. The psychologist said I was smart, and made me repeat “I am very smart” several times to reinforce that to my twelve-year-old self. And then he gave me and my mom some ideas for how to adapt my studying to better suit my learning style — ideas that have served me all the way through high school, an undergraduate degree and to this day in the workplace.

Most learning disabilities are first noticed by teachers in the classroom. I don’t remember how many kids were in my classes in middle school. But I have often wondered, if there had been fewer kids in my class, would the teachers have helped me sooner? It might have saved me a couple years of bullying and abuse and consequentially a lifetime of anxiety and depression.

If the class had been larger, would I ever have gotten a diagnosis? Would I ever have learned any study skills? Would I ever have finished high school and gone to university?

Learning disabilities are not inherently a problem with kids; they are a problem with the way that education is done. Kids with learning disabilities have average or above average IQs, but lean strongly towards a particular learning style, or otherwise have needs that are not met by the school system.

Teachers who have personal relationships with the kids in their classroom, who really get to know the kids, make a huge difference to the quality of the learning that happens for everyone. Larger classes affect everyone’s learning.

But students with disabilities will be hurt the worst when they don’t have good access to their teachers. Students with learning disabilities, including those with NLD, ADHD, dyslexia and autism will suffer not only academically but emotionally and economically in the long term.

Many kids are diagnosed with other kinds of learning disabilities much younger than I was; they need their teachers’ attention, too.

The Tories’ announcement opens the door for cuts to education. Larger classes means fewer teachers will be perceived to be needed, which justifies cutting funding for education at the next opportunity. Then there is less money for education, which means more reason to cut teachers and make class sizes larger. This is the strategy of a government with a long term plan to erode public education.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Wikimeida Commons/Michael Anderson