A new report by the CCPA, Eduflation and the High Cost of Learning, shows that the average university tuition bill in Canada has grown three times faster than inflation over the last 20 years. It’s also outpaced the growth of family incomes, making university considerably less affordable for the average Canadian family than it used to be just 20 years ago.

The report tracks trends in university affordability for families by looking at the ratios between tuition fees and median family incomes over time, expressed as an index. The approach is very similar to the way we talk about housing affordability. The authors also compared tuition fees with poverty-line incomes to examine affordability for low-income families separately. Here’s what they found.

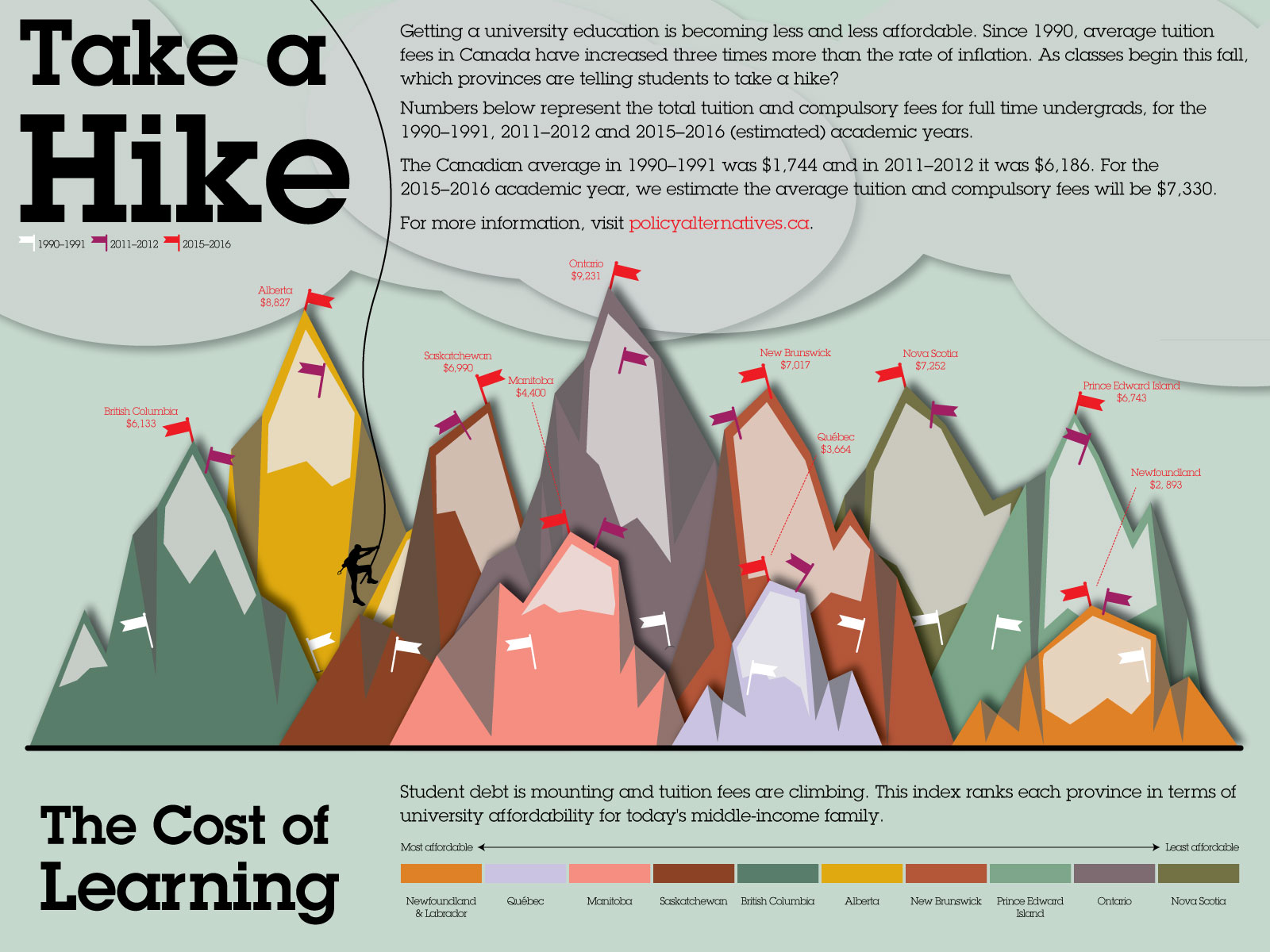

Since the 1990s, education affordability declined in all provinces except Newfoundland and Labrador, where recent government policy of tuition roll-backs and freezes, combined with strong income growth, have significantly improved affordability for families earning the median income. Note, however, that while Quebec remains one of the most affordable provinces to go to university, their education affordability has worsened significantly over the last 20 years.

The report also looks at university affordability for low-income families and the findings are pretty grim. Affordability has worsened significantly more for low-income families than for the average Canadian family.

If tuition and incomes continue to grow at the levels we’ve seen over the last four years, the report projects that education will increasingly become out of reach for children growing up in low- and modest- income families.

One of the big contributions of this report is to highlight the extent of provincial differences in education. The lack of a national higher education strategy in Canada means that we don’t actually have a higher education system in this country. What we have is 10 different systems, with very different tuition fees and student financial aid programs that have their own complex structures and eligibility rules.

We are all Canadians, but where one grows up makes a big difference in terms of education affordability. Education is between two and three times more affordable for a student in a median-income family in Newfoundland than it is for a median-income student in Ontario.

How does B.C. measure up? We’re in the middle of the pack in terms of affordability. But there isn’t much to celebrate — I suspect the recent moderation of average tuition growth in B.C. is largely a product of the five “new” universities the government “created” in 2008 from existing non-university higher education institutions (as they charge lower fees than B.C.’s other seven universities). Our average student loan levels are relatively high and we charge the highest interest rate on provincial student loans in Canada.

How has the worsening affordability impacted students? Growing university enrollment numbers have led some commentators to conclude that it hasn’t. This can’t be further from the truth. Students from higher-income families continue to be better represented on university campuses than their peers who grew up in lower income families (though the latest numbers we have on who goes to university are from 2006 and badly need to be updated).

For students, growing tuition has meant that in most provinces, it is no longer possible to earn enough in a summer job to pay for tuition (let alone living expenses). Worsening affordability relative to family incomes, and growing household debt levels has meant that many Canadian families can’t afford to provide much financial help for their children’s education.

While government-based financial aid spending has increased, much of the support is now provided through loans rather than grants. It’s hardly surprising, then, that student debt ballooned over a generation, doubling in real terms over the 1990s and growing more moderately, but still faster than inflation, over the 2000s. If these more moderate trends persist over the 2010s, I estimate that today’s university students who borrow to pay for their education (58% of all students in 2009) are looking at an average debt load of $34,000 upon graduation in 2016. Students pursuing graduate programs will often borrow a lot more.

The rapid rise of student debt is perhaps the most important shift in higher education over the last generation. To say that it doesn’t have an impact on students is simply not credible.

We know that lower-income students are more likely to borrow to finance their education. This is fundamentally inequitable, because it means that the lower-income students end up paying considerably more for the same education (through interest on their debt) than their peers whose parents can afford the tuition fees up front. There is increasing evidence that high debt levels are an obstacle for many of the highest-needs students as they transition into the workforce and start families.

It’s estimated that over the next decade, more than three quarters of new jobs in Canada will require some form of post-secondary education. As higher education increasingly becomes a standard job requirement, isn’t it time to expand public education beyond secondary schools and into institutions of higher learning and do away with tuition altogether? Many other countries have done this. Data from OECD’s latest Education at a Glance report shows that out of 25 countries that provide data on tuition fees, two-thirds either charge no tuition at all or only charge nominal fees (lower than $1,200 US per year).

After all, it’s hardly fair to lower income students to ask them to incur significant debt and suffer lasting financial consequences just to have a shot at a decent-paying job.

This article was first posted on Policy Note.

What’s Harper up to? Award-winning journalist Karl Nerenberg keeps you in the know. Donate to support his efforts today.