Last week I received an email from a former student asking me for a reference letter. I receive about ten of these requests per year. This particular email was representative of the ones I generally receive. In addition to identifying herself, the courses I taught in which she was a student, and giving me a sense of her program of study for graduate school, the student also took the time to tell me that she found my teaching meaningful. Indeed, she said in the same sentence: “your classes fundamentally changed my thinking for the better” and “I hope you are teaching a lot these days, we need more teachers like you.”

I’m not telling you this to brag. Rather, I want to underscore the painful irony of receiving this email when I did. The irony of this particular moment was that I got this email while I was on the telephone with a person at Employment Insurance reporting services.

This lovely gentleman, Jonathan, was helping me file my bi-weekly EI report. He asked me what the small sum of income I had claimed was for, because he suspected it was what had flagged my report and required me to call in. I replied, “I am team-teaching one year-long course at Dalhousie University.” What did I mean, he asked, did I have a PhD? Yes, I replied. I have been a precariously employed Contract Academic Faculty (CAF) worker since I finished my PhD in 2008.

Jonathan was not appeased.

Why, he asked gently, was my pay so low? Surely this wasn’t what I made on a weekly basis as a PhD holding university teacher?

I explained that for four years I had sequential 10-month salaried CAF positions at Dalhousie, and last year I held a 12-month salaried CAF position at Mount Allison University, but that with budget cuts and lack of retirement and retention practices this year I was virtually out of work. And the work I did have? Well, yes, I had to admit to Jonathan that it really did pay that little.

He sighed. He apologized to me for my low wages. Then, Jonathan said, “let’s get this claim submitted. You’ll need it.”

Seeing Contract Academic Faculty

While it doesn’t surprise me that Jonathan at the EI headquarters was surprised to hear about the material working conditions of precariously employed academic sector people it does constantly surprise me that my tenured colleagues seem to be shocked by the realities of CAF life and work.

That shock was made more present for me a few weeks ago when, in a genuine and desperate attempt to remain positive about CAF working conditions that structure my life and my partner’s life, I wrote a love letter to Contract Faculty. Tenured and CAF colleagues from across the country contacted me to express their appreciation for the post. The difference, though, was this: tenured colleagues were surprised and devastated by this partial list of lived experience. My CAF colleagues? They were relieved to be seen, and to have some of their experiences made public.

At Dalhousie University a sessional employee — meaning someone who gets paid per one-semester course — earns $4,565 before taxes. That means a CAF would need to teach four classes per term to reach $18,000 (or $1000 less than the amount that workers at the University of Toronto are striking over). For reference, most tenure-track faculty members teach between two and three courses per semester.

Why the difference in teaching load? The argument goes that a tenured faculty member splits their work between teaching, research, and service while a CAF is not expected — or supported — to do research and service. In reality, though, CAFs are on the job market, and hiring committees look for grant-winners, high rates of publication, and involvement and innovation in the discipline (aka service). This exploitation of precarious workers has been ongoing in post-secondary institutions for years now. What has changed?

The short answer is: publicity. The last month has marked a shift in the places we talk about the working conditions of Contract Academic Faculty. February 25 was the first National Adjunct Walkout Day. Participants in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Canada used the day to stage walkouts, protests, and informational teach-ins about what it means to be contract workers in academia. These protests took place on campuses, in town centres, and most voraciously, on the Internet.

In the weeks that have followed we in Canada have seen teaching assistants at the University of Toronto take to the picket lines to advocate for a living wage. These strikers are graduate students and precariously employed contract workers. They are fighting for fair remuneration for their vital work, they are flagging the untenable working conditions of the university system at large, and they are fighting against gross misrepresentation of their demands.

The contract workers at York University are on strike to protect and uphold their collective agreement and, crucially, for tuition indexation. There have been numerous articles in mainstream media about the strikes in Toronto. What is so notable about the media attention is the attempt on the part of many journalists to connect Teaching Assistant and CAF working conditions to the sustainability and viability of post-secondary education.

Yes. Finally.

Without public pressure coming from students, parents, and concerned members of society, we will continue to witness what Bill Readings predicted in the 1990s: the university in ruins. And if you are tempted to respond “let it burn” then let me encourage you to think about what non-intervention in untenable situation can mean. No, not everyone needs to go to university, but everyone who wants to pursue post-secondary education should have the opportunity to apply and, if accepted, have access to the means for paying for their education without being spiraled into decades-long crushing debt.

Further, once in a post-secondary educational system those students should have the opportunity to be taught by people who are actively researching in their field, who are themselves being fairly recompensed for their labour, and who are not consistently splitting their attention, time, and energy between their work and the work of securing more work.

How do we keep this struggle at the forefront of the public’s mind? Erin answers this question, and more in the second entry in her two-part series, “With toil and solidarity we can solve Canada’s academic labour crisis.”

Erin Wunker holds a PhD in Canadian literature. She is Chair of the Board of the social justice organization Canadian Women in the Literary Arts (www.cwila.com) and co-founder and weekly blogger at Hook & Eye: Fast Feminism, Slow Academe (www.hookandeye.ca). She is an award-winning teacher who is currently a CAF at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

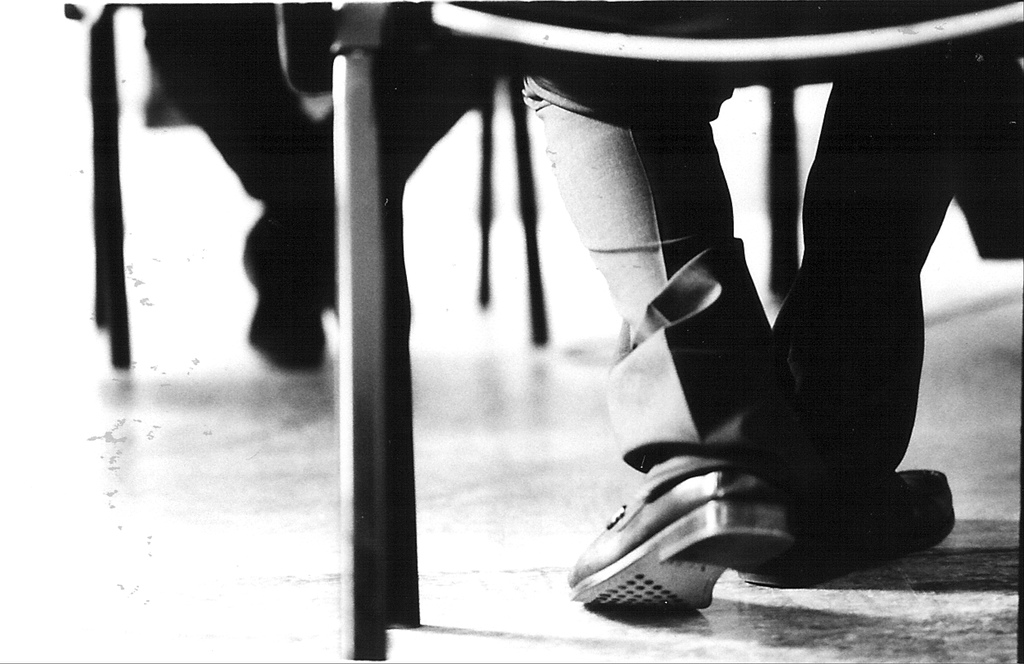

Image: Flickr/ilriccio