Activists, community members, harm reduction workers and radical scholars have long called attention to the relations between K-12 schools, universities, and policing; prison expansion, gentrification, and the privatization of public space; houselessness, alternative street economies, substance use, and mental illness. As activists and scholars working in Toronto who are deeply concerned about these issues, we witness daily how neoliberal capitalist interests are directing money away from the people and away from social supports and programs. We know that it is not a coincidence that all of the following is happening simultaneously: the chaos of discussions around public health, housing and the mayor’s increasingly authoritarian decision-making power and lack of accountability; violent shelter hotel and encampment evictions; and calls in recent months for the increased “securitization” of public schools and the Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) campus.

In response to an incident of sexual assault on October 26, 2022 at TMU, an online petition was circulated, calling for an increase of security on campus. The petition garnered over 13,000 signatures. On November 7, 2022, TMU announced “measures to enhance security on TMU campus” in response to “recent incidents on our campus [that] have been especially concerning for our community members.” The announcement details how TMU’s Community Safety and Security Team have already increased the number of security guards and municipal police on campus to protect what they call, “the wellbeing of our community.”

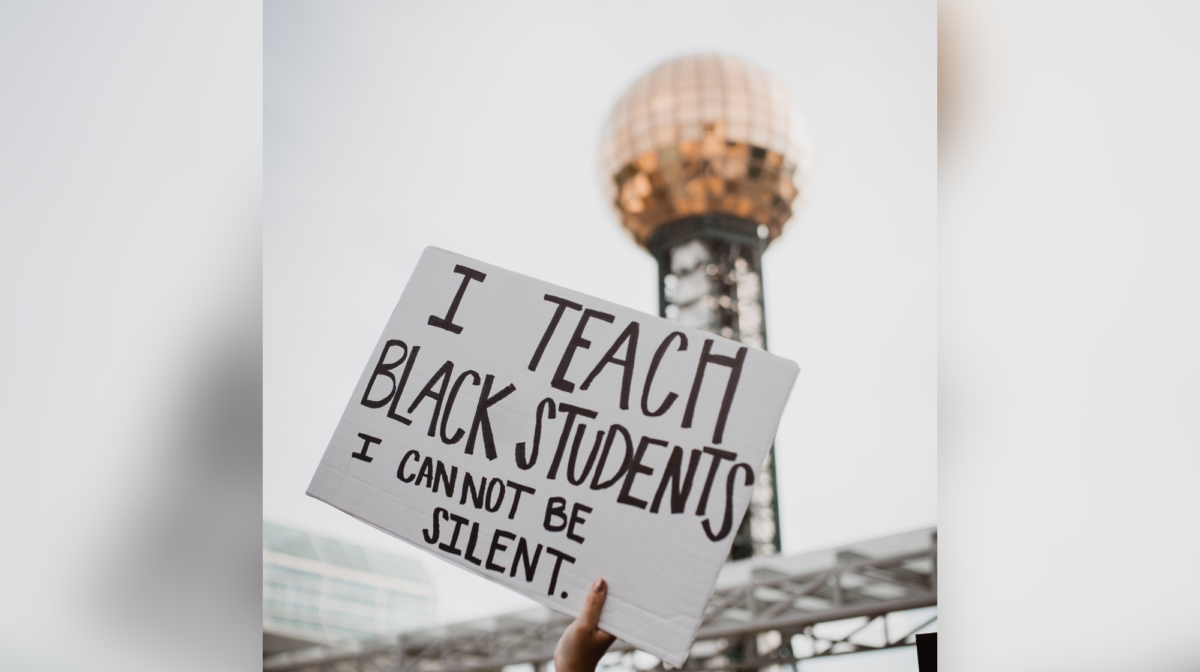

On Friday, December 2, 2022 students of York Memorial Collegiate Institute walked out of their school and marched with their community supporters to the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) offices to protest the horrific conditions they are being subjected to in their school. As the walkout and press releases by students demonstrate, students and those who love them are acutely aware of the violence in their schools, wherein police are not the answer, but indeed very much part of the problem. Students at York Memorial report being subjected to racial slurs, racist remarks, and discrimination from teachers; they do not feel supported or respected as human beings. The frequency with which police are called to the school has not improved the situation, instead students report being further terrorized by the presence and behaviours of armed officers. Certainly, many of them, especially those who are Indigenous, Black, and/ or poor people, are starkly aware that police do NOT keep them safe. And yet, beginning on Monday, December 5 (and continuing for several days) an urgent special meeting of the TDSB Board of Trustees discussed a proposal to bring back the School Resource Officers (SRO) program, after voting to remove that same program from its schools less than five years ago.

Tireless organizing and activism by students, parents, educators, community members and educational activists led to the correct decision to remove cops from TDSB schools in 2017, and it is unconscionable that the board would now even consider reinstating that program. We add our voices to the many asserting that any move to revive the SRO program will send a clear message to the students and families most impacted by this decision, that the TDSB does not care about their well-being, about their education, or about their futures. Cops in schools do not end violence in schools; cops in schools subject students to normalized police surveillance, harassment, intimidation, assault, racial profiling, and criminalization.

At TMU (formerly Ryerson University), activist students – most notably Black student activists – have described being subjected to relentless surveillance and harassment, especially when organizing against the presence of police in their school. Organizing and activism led by students forced the university to suspend plans for additional police presence on campus a few short years ago. Instead of committing to the long-term work of creating safer academic and local communities rooted in strong relationships, shared resources and harm reduction, universities too often prefer to “wait out” generations of radical students. This appears to be the case at TMU, as the senior administration has sought to maintain its authority through attempts to silence and push out student activists (Igbavboa, Singh, 2020). In the recent announcement regarding safety at TMU, the very first of the “community supports” the university identifies as key partnerships in these efforts is Toronto Police Service.

Due to the ongoing resistance of the Indigenous landback movement, and increasingly militant action and refusals of normative white settler colonialism in academia, TMU has been forced to rebrand from emphasis on colonial historical authority (via the Ryerson name and legacy) to an emphasis on neoliberal capitalist authority (as an institution of a global city/metropolis). Universities seek to capitalize on sophisticated spaces of urban “diversity” and capitalist development, while erasing the poverty, criminalized activity, and alternative survival economies that always already exist in gentrifying cities. This involves the construction of disposable groups of people through carcerality – using surveillance and police violence to criminalize ‘social problems’ and the (disproportionately Black, Indigenous) populations most directly subjected to them. The university has been mythically constructed as the antithesis and even solution to such urban social problems and peoples; hence TMU and the University of Toronto in downtown Toronto and those of us who work in these institutions can think of ourselves as progressive and embracing of international diversity without the burden of addressing the power relations and social hierarchy of racial capitalism (Leonardo and Hunter, 2007).

A report on anti-racism that was published in 2010 by Ryerson/TMU demonstrates the way racialized students, faculty and staff experience racial violence from the presence of cops on campus (Final Report of the Taskforce on Anti-Racism at Ryerson, 2010, pg. 30). This message has since been consistently communicated to the university administration by multiple student groups, faculty, and external community members, while additional research, such as the 2020 report by the Ontario Human Rights Commission details that Black Toronto residents are disproportionately targeted by police violence.

The Scarborough Charter is a pledge to fight anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion in higher education. Under pressure from activists after failing to sign on from the outset, Mohamed Lachemi, President of TMU, signed the Charter in October 2022 (Djan, 2022). A specific call to action listed in section 3.1 of the Charter states that Universities and Colleges Commit to Enabling Mutuality in Governance by:

3.1.1. reassessing the existing campus security and safety infrastructure and protocols with a view to protecting the human dignity, equality and safety of Black people on campus

3.1.2. undertaking periodic climate surveys that consider local community relations, to assess and guide initiatives to build inclusive campuses in a manner that is responsive to the specific needs of Black faculty, staff and students.

Despite the commitment of TMU to address anti-Black racism in the university, TMU is engaging in policy to address sexual violence in a way that centres white neo/liberal values. It has ignored the broader knowledges of students, faculty, staff, and community members that would support measures that can address the overlapping, co-constitutive nature of racial, sexual, and state violence (Colpits, 2021). In addition to discounting the labour of those who have worked for community-centred, trauma informed, non-carceral approaches to collective wellbeing at the university, TMU’s decision to increase policing on campus (whether by private security companies or the TPS) directly conflicts with the commitments of the Scarborough Charter. TMU’s touting of its ongoing intimacy with TPS as a way of addressing sexual violence dramatically fails to recognize the multitude of ways that racialized sexual violence is enacted in campus spaces and the greater community—including by police themselves.

It is necessary to reflect on who feels (and who does not feel) reassured by increased policing practices in schools, and whose wellbeing is nourished (and who is directly harmed and traumatized) by police presence in schools and communities. Increased policing increases violence, especially violence towards Black and Indigenous community members, and those who are negatively impacted by lack of housing, by poverty, and by the criminalization of substance use and sex work.

TMU has implemented more police and security officers, disregarding substantial evidence of the effects of increased racial violence from increasing security on campus. Consistent efforts led by Black student groups over the years have detailed how actions to increase security on campus adversely impact the greater TMU community. As Dr. Anne-Marie Singh tells us, “these calls for increased security ignore the findings of both the Anti-Racism Taskforce Report and the Anti-Black Climate Report about the violent policing of Indigenous and Black bodies by campus security – Reports which the Administration accepted with much fanfare but have now tossed aside” (personal communication, December 20, 2022). TMU administrators are thus well aware that increased policing on campus only provides a sense of safety for community members who feel protected by systems of white supremacy and the social hierarchy of racial capitalism.

The clandestine violence of calling for a strengthened police presence on the TMU campus cannot and should not be ignored, nor should it be viewed in isolation from the ramping up of a racist and gendered moral panic about student violence in public schools. Bringing cops into schools is intricately connected to neoliberal capitalist interests, as is deploying cops to violently evict encampments and shelter hotels, as are court injunctions and the deployment of cops to violently extract Indigenous peoples from their land. Institutions of police direct money away from the people, as evidenced by the mayor’s unabashed 48 million dollar increase in funding for the police instead of addressing the crucial need for greater supports for housing, health and education.

At the same time that Black students are leading resistance to police presence in their schools, the poor are defending their communities and rights to permanent affordable housing, and Indigenous Land Defenders are continuing centuries of resistance to the unethical and illegal occupation of colonizers on their traditional territories. These issues are intertwined, and we stand in solidarity with those who are leading actions that imagine a future that transcends white settler colonialism.

It is crucial that new and current students of all ages know of a narrative that differs from the common and timeworn myth that police protect and serve all of us equally and equitably. If we must walk out from schools and engage in hours, months, and years of advocacy and resistance to make it known, then we are valid and justified in doing so. Demands to increase police presence in schools and communities disregard the realities of those who know, live, and survive police violence as anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, anti-poor violence. Cops do not keep our communities safe; cops keep normative white settler colonialism intact