This article was originally published on August 30, 2012, in Montreal, by The McGill Daily.

In mid-summer, almost four months after the Quebec student strike of 2012 had entered uncharted territory as the longest in the province’s history, Premier Jean Charest played his final card. With CEGEP students prepared to renew strike mandates despite threats of a lost semester, and the Special Law lying in shreds under the feet of a hundred thousand illegal demonstrators, Charest called a provincial election, over a year before his term was set to expire. On September 4, Quebec residents will enter voting booths.

The election has had a profound effect on the strike movement. The unlimited strike has been stopped or suspended in every CEGEP, with a high enough number of CEGEP students (newly eligible voters) having placed their hopes in the election. Beyond the ambient calls from the state, family, mainstream media, and ‘leaders’ in the student federations for students to get off the streets and ‘go vote,’ the mid-August general assemblies took place under tremendous coercion: administrators threatened not only the cancellation of the semester, but also to fail students in all winter courses. Added to these factors was the threat of violent police intervention to break picket lines, and the prospect of their associations being fined out of existence under provisions of Law 12. (Meanwhile, at McGill, the SSMU celebrates the re-opening of a campus bar refurbished with over half a million dollars of students’ money).

While the student strike is far from dead — numerous university associations are voting against a return to class — the election call indisputably took a toll. For the first time, students’ rapport de force (power relation) against the state was significantly compromised.

However, polls indicate that the Liberal Party will fail to win a fourth mandate. Will Charest’s wager ultimately fail? Alas, once he retreats to the relative quiet of private soirées with the Desmarais family and a few multinational corporate directorships, the rest of the ruling class may look upon him as a true and lasting victor, for he effectively persuaded students engaged in an anti-systemic struggle to shuffle into polling stations, line up to dispassionately cast their ballots, gather in front of television screens in election-night apprehension, and ultimately respect the ‘people’s verdict.’ If this collective self-immolation comes to pass, Charest’s triumph will far outlive his successor’s term in office, because with the streets cleansed of the most threatening social movement North America has seen in a generation, the managerial classes will enjoy renewed peace, their mechanisms of control reaffirmed, rid of the multiplying challenges, both ideological and material, which the strike has posed to the ongoing expansion of the logic of capital into all sectors of life.

Our only option is to defy this prescribed electoral death.

First, if the September 4 election indeed leads to major concessions on student demands by the newly elected party, it is the rapport de force that we have created with the state, and not our engagement in the electoral process, that will be responsible for our gains. The Parti Québecois (PQ), which leads in the polls, has promised a temporary tuition freeze, but not out of any genuine commitment to accessible education: in 1996, then-Education Minister, now-PQ leader, Pauline Marois presided over an attempt to raise fees by 30 per cent (a strike put an end to the plan).

It was the crisis generated this past spring, not the lobbying of political parties or scripted appeals to the electorate, that made it politically opportune for the PQ to oppose the Liberals’ plan to raise tuition at all costs. It was massive student mobilization that ultimately forced the election call and made the tuition hike an election issue. And it was sustained economic disruption that triggered the more visibly repressive measures that have cost Charest support from the segment of his base that favors a veneer of social peace above the machinations of accelerating neoliberal exploitation. Finally, it will be continued mobilization, through strikes, mass demonstrations, and economic disruption, that will force a PQ government to keep its promises.

We can do away now with the pretension that the student strike is only about a tuition hike or accessibility to education. Regardless of how many grévistes remain ready to return to the classroom once the National Assembly enacts a tuition freeze, an anti-systemic current has underlain the strike from the beginning. With many strike mandates requiring the abolition of the 75 per cent hike as well as the reversal of a smaller 2007 increase, we sought to overturn the decisions of a democratically elected and re-elected government, decisions aligned with the Liberal Party’s stated agenda and enacted legally. Even in its limited demands, the movement implicitly challenged the legitimacy of a government, and thereby the legitimacy of the process that granted it power.

The strike was also always a vehicle for contesting an economic system in its entirety. Free education, our ultimate demand, would be unsustainable under capitalism in its present stage, where in order to survive it must constantly seek out new markets, invent new kinds of production and consumption, and continually extend the rule of capital into territory once regulated by the welfare state.

In this context, the solution we await from an elected government within the existent system can only be insufficient — not inadequate in scale, but of the wrong order. Elections are not a solution because they cannot give us anything worth fighting for. Insofar as we participate in liberal representative democracy, we offer ourselves up to recuperation by the forms we need to abolish, and we accept surrender in a struggle against capital and its managers, and against alienated activity, that has barely begun.

For the social movement that has erupted around the student strike, placing our hopes in the voting booth would represent the ultimate abdication. We can repeat the fact that no party with a chance of winning would fully meet students’ demands. That those who would be most affected by the tuition hike are under the age of 18, and as such, cannot vote. That Charest has instrumentalized the electoral process to suppress a social movement.

But much more elementally, the search for an electoral solution is a betrayal of the grève générale illimitée, because the last six months have shown more than anything that real political contestation takes place in the streets, where relationships of undelegated power are truly at play. The streets are precisely the space that this election — any election — seeks to close off to politics. In the spring, the streets were radically open: to moments marked by the freedom to find new ways of relating, to passionate activity, to the sensation of breaking away. Behind the curtains of voting booths, we don’t yet know what it is that we will lose.

A movement founded on direct democracy, where people linked by shared conditions chose to come together to make decisions about the next day, the next week, decisions that they themselves would apply, must not succumb to the liberal order it has always challenged, in which once every five years we have the right to express our opinion about which politician should be handed power over our lives. A right that we are fervently exhorted to exercise, as though in a series of diversions from the exact terms of a contract, in which we renounce our freedom to engage in anything other than peaceful displays of dissent should we become dissatisfied with the government. The prevailing logic of representation is carefully crafted to exclude activity other than the playing of varied parts in a well-rehearsed spectacle.

The strike has given life to something different, something dangerous yet fragile which surpasses the fleeting experiences of the streets. An election — its plain question, its clear choices — promises nothing if not an answer, a solution, an end. No promise could so starkly reveal the need for refusal and for resistance. There are too many questions unasked, too much brutality unanswered, and too many battles yet to begin.

Kevin Paul is a first-year Law student. He can be reached at [email protected]. This article was a finalist in the opinion-writing category of Canadian University Press’ John H. McDonald awards for excellence in student journalism. It was first published in The McGill Daily and is reprinted here with permission.

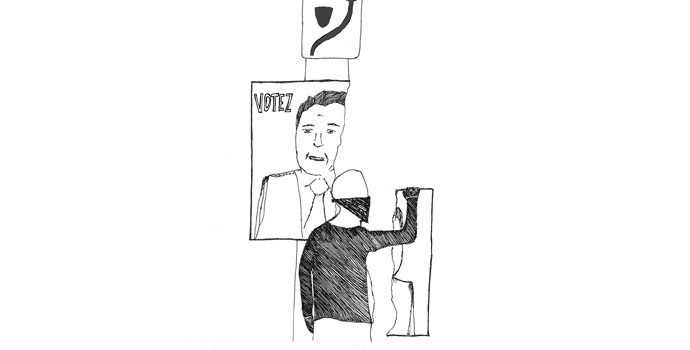

Photo: Jacqueline Brandon/The McGill Daily