“It moved me to tears.” That’s what one student said when I asked my history class what they thought about The Voice of Women: The First Thirty Years. We had just finished watching the film together in an afternoon class. It was February 2016, and I was teaching “Contemporary Canadian Women’s History,” a third-year undergraduate history course at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario.

Somewhat surprised to hear such a profound level of emotional engagement, (and indeed, wondering if in fact the student was being sincere), I asked them to say a bit more about their comment. The student explained that it was indeed a heartfelt reaction: the thought of VOW members, during the Vietnam War, arranging for Vietnamese mothers to visit Canada in order to meet with American women was profoundly moving.

When the Vietnamese and American women met each other, with tears in their eyes, one said that she hoped the son she had lost to war had not had the opportunity to harm the other’s boy before he died. It was a very poignant moment. That is what brought the student in my class to tears.

In addition, students were gripped by the thought of VOW members knitting baby clothes in camouflage colours as a subversive act of war resistance. And, the students marvelled, who knew that VOW members asked Canadian mothers to work with the tooth fairy?! That is, who knew that Canadian mothers challenged each other to collect their children’s baby teeth and send them to a lab at the University of Toronto where a physicist, Dr. Ursula Franklin, could collect enough data to demonstrate the residual effects of nuclear testing?

Those same women alerted each other about when it potentially was unsafe to serve their families with milk that might have been contaminated by nuclear fallout. “Switch to powdered milk,” they advised each other. Meanwhile, the data gathered from the tooth project meant that VOW could push successfully for a partial ban on nuclear testing. How clever! How profound! How powerful!

One thing the students concluded after watching the film: Never underestimate the collective power of women working together for a cause.

I used this film in week six of my 12-week undergraduate history course. Prior to this, we had spent classes considering definitions of feminism, thinking about Canadian women’s participation in the Second World War, the displacement of women from the paid workforce as part of the return to a peacetime economy, the suburban experience and the baby boom, the impact of the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, and calls for the creation of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women.

With each of our discussions, I had asked students to consider whether they thought particular actions on the part of Canadian women were “radical” or not, leaving it up to the students themselves to arrive at a definition of that term.

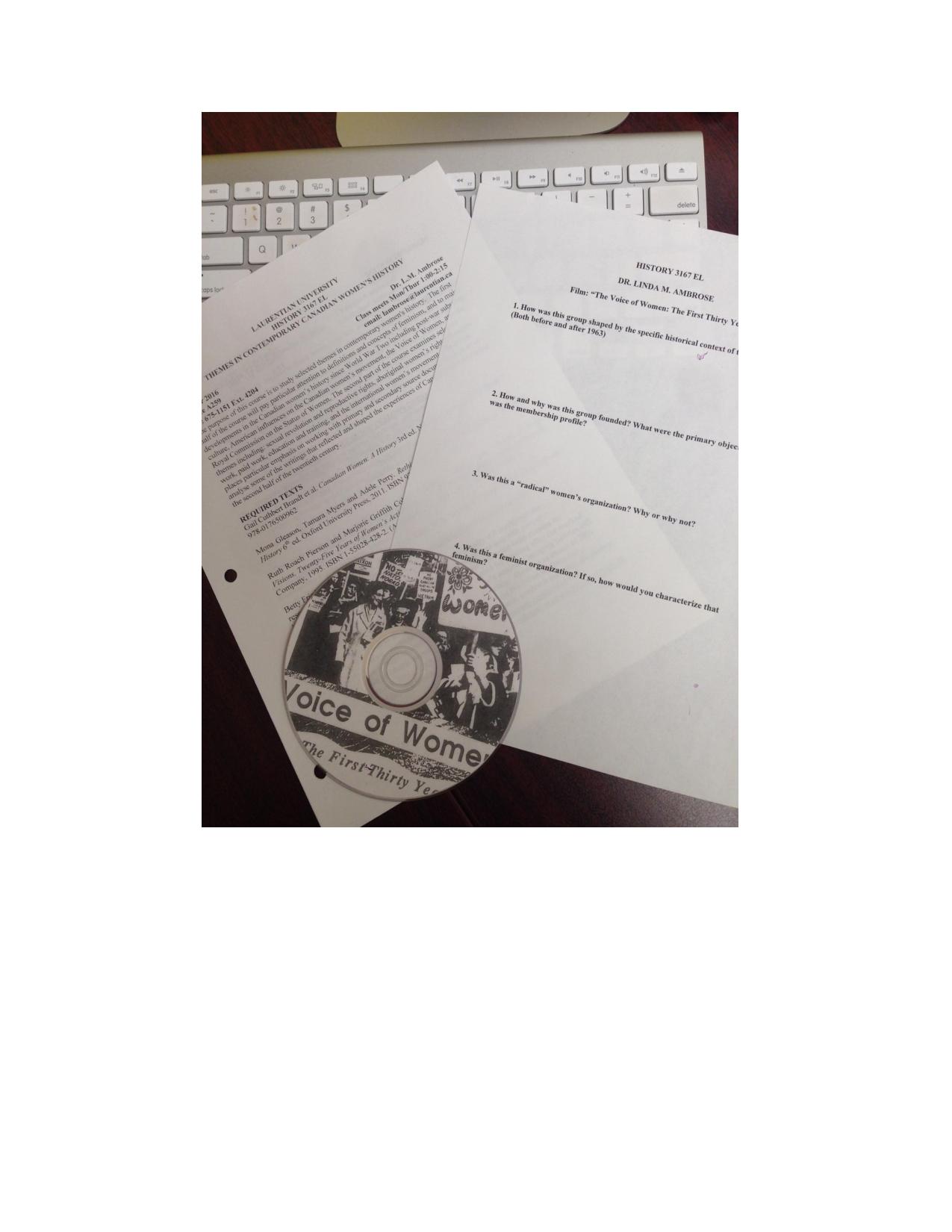

When it came time to learn about the Voice of Women, how the group came into being and the kinds of campaigns they launched throughout the 1960s and 1970s, I used a printed handout to guide students’ viewing of the film so that they were actively looking for answers to particular questions while they watched. As the credits began to roll at the end of the documentary, I once again posed that now-familiar discussion question: This group — the Voice of Women — was it radical? Why or why not?

Students were quick to point out that flying to Moscow at the height of the Cold War, lobbying department-store shoppers to avoid putting war toys under the Christmas tree, being branded either as Communist infiltrators or “dupes,” and enduring the reputational scorn of media, neighbours, and family members must surely be counted as courageous political acts. Was this radical? The students concluded that in that historical context, yes, it was.

As our discussion continued, I prompted the students to talk to each other about whether they considered VOW to be a feminist group, and if so, how they would characterize that feminism. Once again, the room buzzed with their conversation. Maternal feminism, perhaps? Liberal feminism? Radical feminism? These were the terms that the students offered up and debated among themselves.

Released in 1990 to document VOW’s first 30 years, the film itself will soon be 30 years old. Yet for the undergraduate students in my history classroom, who were not yet born when the film was produced, this is still a very valuable learning tool. This film was the catalyst for a serious discussion about another chapter of contemporary Canadian women’s history.

Not only did it move one of them to tears, but it moved all of them to a deeper appreciation of the power of women’s collective action.

Thank you, VOW, for providing me and my students with this valuable pedagogical tool.

To purchase a copy of the VOW film The Voice of Women: The First Thirty Years, please send an email to [email protected] or telephone (416) 603-7915