As an international doctoral student in Canada, I am experiencing various emotional challenges shared with others in the graduate student community — the sense of alienation from my work, my friends and my intellectual community. As borders remain closed to non-essential travel, I am unable to return home to be with my family — a particularly difficult reality as I prepare to miss my grandmother’s 100th birthday. And while I am, perhaps selfishly, disheartened by these realities, I know so many others are in the same boat — missing weddings, birthdays and funerals as we collectively navigate what it means to “shelter in place,” isolated from our loved ones, and missing out on the important sense of connection which is so integral to our very humanity.

While the profound sense of alienation and loss is likely universal to all graduate students during these difficult times, the challenges faced by international students are, in many ways, exceeding those faced by their domestic counterparts. This is true insofar as international students are by and large unable to travel across borders to be with the family and friends who might otherwise offer them financial or emotional supports, but it is also true to the extent that international students are being systematically forgotten and left behind by the programs intended to help the most financially vulnerable.

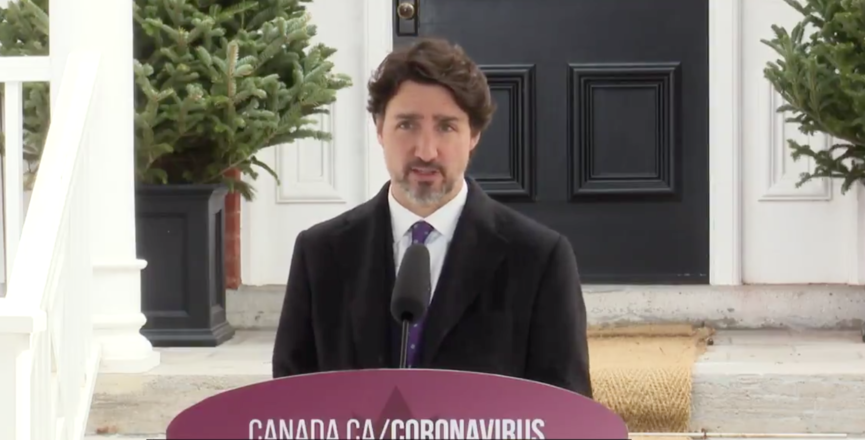

The recently announced Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) program does not, in its current form, include international students. I think this is a mistake. As an international graduate student, I see the work that myself and my peers put into our research, our advocacy in our Canadian communities, and in educating Canadian students. We invest so much of ourselves into our Canadian institutions and communities. Moreover, many of us are financially vulnerable. The decision to exclude international students exacerbates existing inequalities in funding available to graduate students (e.g., in normal conditions, there is far more grant funding available to domestic students in Canada, which international students are ineligible to apply for, and international students are limited by their study permits in terms of how many hours they can work off campus).

Many graduate students rely on summer teaching and other jobs to make ends meet throughout the summer months — jobs which are being lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Personally speaking, I have lost more than one source of summer income due to the pandemic, including an opportunity to teach for the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth Program at Princeton University. Like everyone, international graduate students plan their summer budgets on the basis of expected (e.g., guaranteed by contract) income. When this money is suddenly lost, they find themselves in precarious financial situations, in many cases struggling to make ends meet. The financial difficulties being faced are not only faced by the domestic students the CESB sets out to help; they are also faced, often in more extreme ways, by international students.

Finally, we must also consider intersectional dimensions of disadvantage which can worsen financial and other hardships in this time — of which there are many. Speaking only for myself, I am a first-generation college student from a working-poor background. I do not have the luxury of familial financial supports to fall back on at this time. Where I am unable to make ends meet, there are not resources I can fall back on to pick up the slack. And that is why we have federal leadership to depend on in times of crisis.

The federal government should be willing to support international graduate students who were encouraged to come to Canada to teach and research; it is the morally right thing to do in this time. I call on the federal government to be in solidarity with the diverse and hardworking international graduate students who contribute so much to the intellectual life and productivity of Canadian institutions of higher education. We look to the federal government to invest in us the way we invest in our research, teaching and activism year round.

Heather Stewart is a philosophy PhD candidate at Western University. Her research interests lie at the intersection of feminist philosophy, political philosophy, and bioethics with a specific interest in the philosophy of microaggressions.