On August 19, the student paper for the University of Western Ontario, The Gazette, published an article online titled “So you want to date a teaching assistant.” The article, meant to be humourous in nature, received widespread criticism for making light of sexual harassment in the workplace, targeting graduate students in an already precarious and vulnerable working environment and for perpetuating rape culture on campus. In response, the newspaper published a series of statements before finally apologizing, withdrawing the article and agreeing not to publish the issue in print. The article has also been removed from The Gazette’s website.

Welcome to your free online workshop, “Satire and the Apology in Contemporary Journalism!” As your teaching assistants for this course, we would like to remind you to refrain from all of the recommendations listed in the recent Gazette article written by Robert Nanni, “So you want to date a teaching assistant,” with the exception of the advice to work hard in the course (and we do hope that you will work hard from here on in). Your objectives for this brief workshop are:

- To develop a thorough understanding of satire, as well as its use and misuse in contemporary journalism;

- To demonstrate your knowledge of the distinction between the rhetorical form known as the apologia and the acknowledgement of wrongdoing known as the apology;

- To put the knowledge you have gained from this course into practice, especially if you are on the editorial staff of The Gazette at Western University.

With these objectives in mind, we encourage you to read the following pair of short lectures, after which we will offer you some writing topics designed to kick-start your work on this session’s main themes.

“Satire: An Introduction”

Most undergraduate students of English are likely to remember the moment when their understanding of what does and does not constitute satire is clarified. Instead of seeing satire as a broad concept, largely open to interpretation (and often simply mistaken for what is “humourous”), we quickly learn about the broader historical trends in satirical writing. We learn, for example, that Horatian satire is gentler, and seeks to critique important social issues via humour — readers and viewers of Horatian satire are kindly led to recognize the subtle absurdities of daily living and, hopefully, to support or enact positive change as a result; notable examples in contemporary media include The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. Through their lampooning of pressing political and societal issues, both in speech and in facial expression, Stewart and Colbert highlight problems in government policy and behaviour in order to spur positive change.

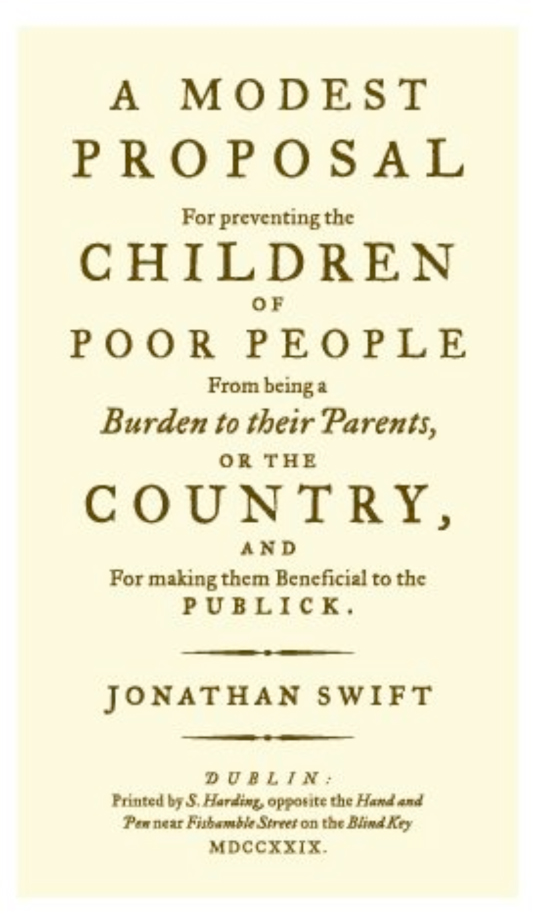

On the other hand, Juvenalian satire is harsher, more cutting. It hyperbolizes events beyond what most reasonable people would recognize as legitimate possibility or suggestion in order to highlight serious ethical or political problems. Famously, Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” written in 1729, sought to call attention to dire poverty in Ireland by offering up a solution that is far beyond the pale — cannibalizing a nation’s youth as a food source: “I have been assured,” he claims, “by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricasie, or a ragoust.”

The extremity of Swift’s proposal — the fact that it is clearly not meant as an actual suggestion, or one that would be broadly accepted — highlights the problem of poverty and hunger by suggesting a solution that most people would not find to be reasonable. In fact, he goes so far as to directly ask his readers for real solutions: “After all, I am not so violently bent upon my own opinion, as to reject any offer, proposed by wise men, which shall be found equally innocent, cheap, easy, and effectual.” Ultimately, the power of satire, then, exists not so much in simply what we believe to be funny as in the fact that it is to be recognized as exaggerated: mocking currently-existing conditions. Add to this the recognition that satire does not reinforce the status quo. It punches up at entrenched power systems rather than down at those who are affected by these policies, behaviours, or societal expectations.

It is for this reason that we — the authors of this piece — do not accept the claim that “So you want to date a teaching assistant?” is satirical in nature. Putting aside for a moment the ethical and power dynamics of a student pursuing a teaching assistant in the hopes of attaining a casual or serious relationship, it is worth considering why it cannot be defended as satire, as some defenders of the piece claim.

First — it is not funny. While some might consider the wording of Nanni’s advice on knowing when to give up as clever or amusing (“They may not be giving you head, but at least they’re giving you brain,” he writes), any potential amusement is offset by the reminder that the pursuing student needn’t give up altogether “after all, there’s always next term”.

Second — to the defense offered by some that it “calls attention” to the issue of harassment of teaching assistants by students — there is no hyperbole at play. It is important to remember that TAs are in a vulnerable position at this stage of their university career. Frequently, they are learning the ropes of managing a classroom and teaching effectively, while working on completing their own studies, and it is not beyond the scope of reasonable assumption that they will, at some point, receive unwanted attention from a student.

We are not talking here about the preposterous suggestion of the widespread, sanctioned cannibalism of children. Instead, we are talking about very real issues of student harassment (let’s remember that TAs are students as well). If this piece were satirical, it would highlight the absurd, improper, and unethical nature of the practice of seducing your educator. The column is, in essence, an advice column, beginning with discovering your TA’s sexual orientation up to and including getting sexual; giving up, in Nanni’s piece, is only a temporary concession to failure.

“The Apologia vs. the Apology”

As an undergraduate, you may have already encountered some of Plato’s work. You have almost certainly heard of his Republic, and perhaps even the famous “Allegory of the Cave.” You may not yet have had the chance to read about Plato’s Apology, however, so we will offer you a short synopsis. Socrates has been accused of corruption and heresy, and the Apology depicts the speech he offers as his defense, as well as his verdict and sentencing. Keep in mind, of course, that Socrates is firm in his belief that he has committed no actual wrongdoing, and his speech bears this out. This is an example of the rhetorical form known as the apology, or apologia — we’ll use the latter term to distinguish it from the expression of remorse more commonly associated with the word “apology.”

The apologia is not a means by which Socrates offers remorse. It is a means for him to say, “I’m sorry that you were offended, accusers, and am here to tell you: I have done no wrong.” Indeed, Socrates accuses his accusers of hypocrisy, proposes that he be rewarded instead of punished, and repeatedly insists that his arguments rest on solid ground. The apologia is not meant to show regret or penitence. It is used to vindicate the accused, as a mode of self-defense, and as a way of persuading an audience that the accused should be accepted back into society with open arms.

The Gazette issued three responses when it should have only issued one. The first response was a complete lack of remorse and attempt to pass off the article on dating a teaching as satire. Above, you will find a detailed explanation from both a literary and ethical perspective as to why that response did not cut it. The second response was an apologia; like Socrates, the paper apologized for producing a piece that caused offense, but made no effort to take responsibility for the piece’s contents. It also implied that criticism of the piece was ungrounded and the uproar unjustified. It was only after international media coverage on news sites from CBC to Jezebel that an apology was offered that took responsibility for the piece and admitted wrongdoing.

So ends the second lecture.

Homework

The lesson here, of course, is do not issue a non-apology and an apologia when a genuine apology is the right course of action. There is no shame in making an error, and both author and Editor-in-Chief are at fault in this case. But dodging responsibility and writing off the very real concerns that teaching assistants, professors, and undergraduate students expressed about this piece is something to be ashamed of, and the Editor-in-Chief was in a position to address these concerns in a meaningful way. This opportunity has been lost, and we fear that the most recent apology may only be lip-service or damage control in the wake of such widespread and negative coverage.

Then again, there is a glimmer of promise in the latest apology. It is suggested that the The Gazette‘s editorial board will “review its editorial practices…with the advisory board.” Your assignment for the 2014-2015 year, Iain Boekhoff, is to show us the best of what The Gazette has to offer its readership on the issues that matter on campuses, and to get your editorial board to work on addressing the following issues in the pages of your publication:

- Sexual harassment on Canadian campuses — statistics, a history of the issue, prevention, and resources for those who have experienced sexual harassment at Western. Who better to reach out to for this than Equity and Human Rights Services, the Women’s Issues Network, V-Day Western, and the Sexual Health and Consent Education Support Service on Western’s campus?

- Getting to know your teaching assistant as a professional and as a human being — our contracts, our labour conditions, and our work as young researchers in our fields. We advise you to work closely with the PSAC Local 610 and Western’s Society of Graduate Students for this assignment!

We are eager to see you put this knowledge into practice, Iain. As teaching assistants, we care deeply about the welfare of our colleagues, fellow employees, and our students. We look forward to your passing this test with flying colours!

Mandy Penney is a doctoral candidate (and former teaching assistant) and an instructor of writing/communication in London, Ontario. She has been previously published on the-toast.net and in Memorial University’s Postscript: A Journal of Graduate Criticism and Theory.

Diana Samu-Visser is a doctoral candidate and teaching assistant in London, Ontario. She is the managing editor of Word Hoard, Western’s interdisciplinary arts and humanities journal.