The federal election of 2021 showed once again how unsuitable the first-past-the-post electoral system is for our vast and diverse country.

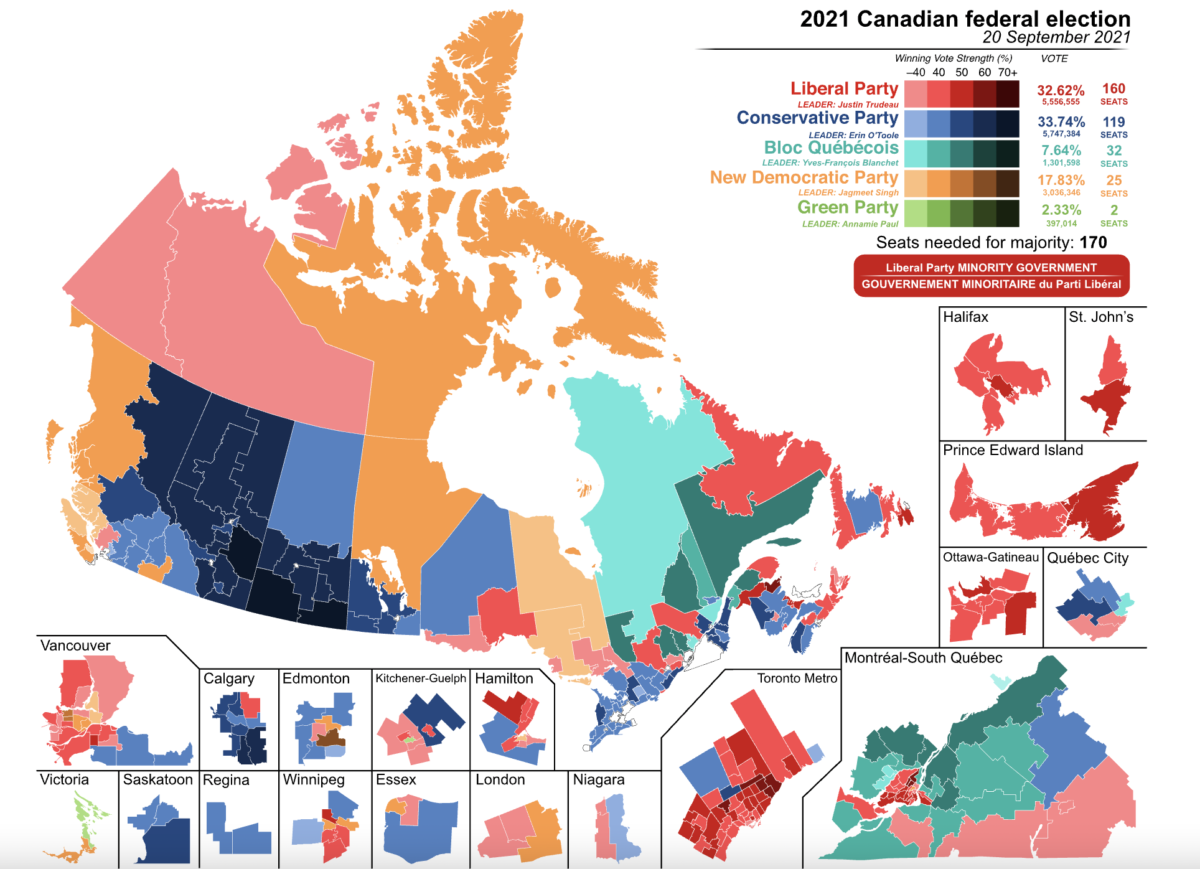

Many have noted that this year, as in 2019, the party that came second in votes, the Liberals, nonetheless managed to win the most seats, 160 (a mere ten fewer than the 170 needed for a majority).

The main problem for the second place (but first in votes) Conservatives was that their votes were too concentrated in a handful of western provinces. In political science jargon, they had a highly inefficient vote.

Liberal votes were, by contrast, hyper-efficient.

Examining the 2021 results, one notes how the Liberals won almost every one of their close races – in one case by 76 votes, in another by a mere dozen!

In September’s election, the Liberals played poker under a lucky star. Every time they needed it, they almost miraculously drew just the right card to complete an inside straight.

The New Democrats were the unluckiest players.

Unlike all other parties (save the far-right Peoples’ Party of Canada), the New Democrats succeeded in increasing their popular vote vis-à-vis the 2019 election. And yet they lost just about every tight race they were in – from Halifax to Berthier-Maskinongé to Saskatoon West.

There is a meme going around that shows how the New Democrats won a mere 25 seats, representing 7.4 per cent of the 338-seat total, while their popular vote share was a respectable 17.8 per cent. The separatist Bloc Québécois won seven more seats than the New Democrats, with a mere 7.4 per cent of the popular vote, less than half the New Democrats’ share.

At least the Bloquistes’ 9.4 per cent of the seats in Parliament gave them a share that is close to their vote percentage. The Liberals did way better. They won nearly half the seats in the House of Commons, 47.3 per cent, with less than a third of the votes, 32.6 per cent.

No wonder so many Liberals are unalterably hostile to any talk of change to the electoral system.

A system that exaggerates regional differences

If the Liberals, and all the parties, were to take a farsighted view, and consider what is good for Canada and not merely their own party, they would realize our current electoral system poses a very real threat to our cohesion and unity as a country.

The fact that the system tends to underrepresent New Democrats – and others, such as the PPCers and Greens – is not, in truth, the worst aspect of first-past-the-post.

What is most troublesome and problematic about our voting system is that it exaggerates and exacerbates political differences among Canadians based solely on geography.

Our first-past-the-post system makes it seem we are more different from each other, from one geographical region to another, than we really are.

Just consider this:

In Toronto, the Liberals elected 48 of the 53 MPs, but they only won 48.9 per cent of the votes in that city. That means with less than half the popular vote the Liberals won more than 90 per cent of the seats in Canada’s largest city.

As for the other parties, the Conservatives significantly underperformed their popular vote share of 31 per cent in Toronto. But they did manage to win five Toronto seats.

The hapless New Democrats got zilch, nada, goose-egg, not a single seat in Toronto, even though they won 14.5 per cent of the votes there. The 357,793 Torontonians who voted NDP did not get even a single MP to champion their concerns and values.

The truth is that Toronto is not anywhere near 90 per cent Liberal. The mega-city is, in reality, only just about half Liberal. But the electoral result tells a far different – and massively distorted – story.

There are real-life consequences to that sort of distortion.

One of those is that in the next Parliament, the views and experiences of Torontonians will be largely missing when Conservative and NDP caucuses meet. When the Liberals meet, Toronto’s concerns and preoccupations will wield excessive and disproportionate influence.

The provinces of Saskatchewan, Prince Edward Island (PEI), and Newfoundland and Labrador provide a similar spectacle of distortion.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the Liberals did not win even half the votes, yet they won all save one of the seven seats.

It was the same story in PEI, where the Liberals fell well below the fifty per cent line in popular vote, but took home 100 per cent of the seats. In that province, the Conservatives had close to a third of the votes, with nothing to show for it.

In Saskatchewan, the NDP managed to garner more than one-fifth of the votes, 21.1 per cent. That is more than three points higher than the NDP’s national popular vote share. But the New Democrats won zero Saskatchewan seats. The Conservatives won all 14.

And so, whole regions of the country get coloured red or blue in elections, while the people who live there are not nearly so monochrome.

Most outrageous result was in 1993

The 2021 election result was not the most outlandish in recent memory.

It gave excessive space to the separatist Bloc, vastly over-rewarded the Liberals and Conservatives in regions where they were in first place position, and penalized the progressive NDP, whose support is based less on geography and more on demography.

New Democrats get a lot of their support from younger voters, from Indigenous people, from the poor and from both unionized and precarious workers – across regional and provincial borders. First-past-the-post does not reward support of that kind.

The most outrageous case of first-past-the-post distortion happened way back in 1993, when the Liberals, led by Jean Chrétien, returned to power after nine years in the wilderness.

In that election, the Bloc (which ran candidates in only one province) managed to win the second largest number of seats in Parliament and become official opposition. The NDP won only nine seats and lost official party status (which requires 12 seats), while the Progressive Conservatives, with close to 17 per cent of the vote, won a miserable two seats!

The results were not so extreme on September 20, 2021, but they were not healthy for the country.

The danger of a parliament which is excessively divided on regional grounds is that local and parochial preoccupations can come to dominate political debate.

We don’t need that at this time, when we should be looking at how to rebuild our society in a fairer and more just way in the wake of the COVID-19 tidal wave.

All parties claim to care about the future of Canada and Canadians as a whole, in all parts of the country. All parties save the Bloc, that is, which quite truculently proclaims it concerns itself exclusively with the interests of a single province.

If they do truly care about the whole country, all parties – again with the exception of the Bloc – should urgently consider how to reform an electoral system which produces a regionally-distorted, funhouse-mirror version of Canadians’ electoral choices.