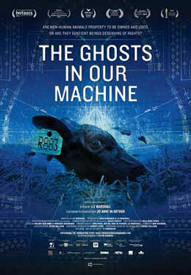

The Ghosts in Our Machine was nominated for four Canadian Screen Awards during a press conference held on January 13 at the TIFF Bell Lightbox cultural centre in Toronto.

The nominations included the Donald Brittain Award for Best Social/Political Documentary together with Best Direction, Best Photography and Best Sound in a Documentary Program.

“Having four nominations is a huge honour,” said Liz Marshall, Director, Producer, Writer, Co-Cinematographer, in a telephone interview on Wednesday. “And it’s also a shining moment for the film.”

Marshall shares the Donald Brittain Award nomination with fellow producer Nina Beveridge and Best Photography nomination with cinematographers Nick de Pencier, Iris Ng and John Price. Sound team Garrett Kerr, Jason Milligan and Daniel Pellerin were nominated for Best Sound.

On January 13, Marshall and her partner looked through the (press) folder and found the page that had the four nominations.

While her partner was “screaming and crying” with joy, Marshall calmly texted fellow producer Nina Beveridge and activist and photojournalist Jo-Anne McArthur, who is featured in the film.

“It’s a real validation when you’re nominated by your peers,” said Marshall.

“And it’s also a platform for the issue that the film is trying to elevate. Animal issues are very challenging and quite marginalized even in the spectrum of social justice movements. So having such high praise for the film is wonderful for the animals, the messages and the purpose of the movie which is really to bring the animals out of the shadows and into peoples’ hearts.”

In 2010 while Marshall was developing the film, which was released on November 13, 2013 in New York City, she was always thinking about what she’d call the documentary. She wanted a title that was “conceptual and nuanced” rather than “in your face.”

At a lecture that fall, Marshall heard Canadian novelist and environmentalist Graeme Gibson refer to nature as the ghost in the machine.

“Something clicked for me in that moment,” said Marshall. So she played around with some variations on that common phrase and everyone loved The Ghosts in Our Machine. “It’s a self-reflective title. It makes you turn your gaze inward and consider the meaning on a personal level.”

The film itself gives insight into the lives of animals “rescued from and living within the machine” of our modern world.

“And that’s actually the mini-synopsis that describes the overall essence of the film,” she said. “I chose to feature a human story to anchor this issue. So that it’s really through Jo-Anne McArthur’s photographic lens and her vision of the world and her work as an activist that audiences are able to access a cast of animal subjects.”

Because animals can’t speak to us through our own language, Marshall felt it was necessary to have McArthur as an entry point into a significant and complicated subject.

“Her photographs are very powerful and invite us to consider animals as individuals,” said Marshall. “I felt she would be a great grounding presence in the film.”

Marshall and the rest of the filmmaking team shadowed McArthur over the course of a year as she did her work in Canada, parts of the United States and Europe.

One of the main story lines in the film follows McArthur on her visit to Farm Sanctuary in the Finger Lakes Region of upstate New York after the rescue from a dairy auction of a cow named Fanny and a calf called Sonny, both destined for a slaughterhouse.

“Farm Sanctuary is a magical place where humans and animals have a very different kind of relationship,” said Marshall. “It’s sort of like being inside a story book from our youth where animals have names and stories and they’re our friends.”

Marshall had spent time at Farm Sanctuary many years ago and was so captivated by the place that she wanted to feature it in the film.

“It just so happens that Jo goes there and uses Farm Sanctuary as her own kind of refuge to restore herself and be with happy animals because a lot of her work is on the front lines documenting the use and abuse of animals within the food, fur and fashion, biomedical research and entertainment industries,” said Marshall.

“That was a really important story line and transitioning to and from Farm Sanctuary. Audiences really feel the effectiveness of that in the film and the ‘ghosts’ are really the billions of animals that are invisible, hidden from our view. And the ‘machine’ is our modern urban consumer driven world.”

Marshall loved working with McArthur.

“We have a natural kinship because we’re both documentarians,” she said. “She was very grateful and invested her time and energy into the film.”

In the movie, McArthur was making photographs for her book “We Animals” that was published in December 2013.

Apart from exploring an exceptionally challenging subject, Marshall always hopes her films pose questions for the audience together with helping them see the world in new ways.

“I don’t want to be told what to do,” said Marshall. Instead she’d rather see a film and have an experience where she has a consciousness raising moment or revelation. “So not only am I learning intellectually but I’m seeing and feeling differently.”

That was the kind of film she wanted to make. “Taking a really gritty tough marginalized almost taboo subject like animal rights and elevating it to a cinematic poetic level was my intention.”

Her other intention was to produce a film without the graphic details that would force many viewers to turn away.

“Because it’s so common for people to turn away from a lot of different issues,” she said. “But especially the animal issue because we’re confronted with it every day when we eat.”

After numerous people told her about the film’s effect on their lives, Marshall decided to produce an impact report that will be available in March.

Some viewers are still thinking about the film almost two years since it premiered at Hot Docs in Toronto. Others changed their behaviour. Several told her that they started talking about animal issues and consider them to be morally significant.

“So there’s a whole spectrum of ways that the film has touched peoples’ lives all over the world,” she said.

Marshall is working with the Humane Research Council, a team of research and communications professionals with strong personal commitments to animal protection, to measure the film’s impact on viewers.

“Because we truly want to understand how the film is helping animals.”

Long before Marshall began developing the story idea for The Ghosts in Our Machine, the thought of producing a film of this nature was turning over in her mind for many years. But it wasn’t until she started “seeing the ghosts around her more and more” that the inspirational ideas began to sprout up everywhere.

Then she started putting together a team to build upon those ideas.

Marshall also credits her ten and a half year relationship with Lorena Elke, a passionate animal rights activist, with “opening up her eyes” and challenging her to focus on animal issues.

So she set about making a film with simple equipment that was without artificiality and artistic effect. Without staging events or scenes. Without studio lighting.

“It’s a naturalist observational approach,” she said. “That’s my favourite way to capture reality.”

In keeping with that approach, Marshall was careful to ensure that the music wouldn’t manipulate the emotions of the audience.

Because Marshall wanted something “understated”, she approached Toronto composer Bob Wiseman to provide a lot of soundscape, moody and ambient textures.

“Bob, the editor and I worked really hard to create a minimalist but moody and textured kind of experience,” she said. “There are some haunting kinds of tonal sounds in the film.”

Marshall’s intimate character driven approach to storytelling has not only been shaped by her interest in the voices of people, like McArthur, who are deeply committed to changing the world.

“It’s an eclectic group of individuals that have influenced me the most,” said Marshall.

“It’s everyone from my mother to Chris Romeike who I went to Ryerson Film School with, to activists and the subjects of my films, to filmmakers, photographers and musicians.”

And she’s also been swayed by watching documentary and fiction films. “It’s the language of filmmaking that I’m drawn to,” she said.

In spite of all the research and planning, Marshall said that there was a great deal of work for co-editors Roland Schlimme and Roderick Deogrades who made their way through over 100 hours of footage shot during an 18 month period.

“Roland’s gift is to sit before a mountain of material and patiently watch everything,” said Marshall.

Although there were many meetings and discussions between Marshall and the editors, Schlimme did a considerable amount of screening while Marshall was still in the field gathering material from different scenes. It took him four months to create the assembly edit, which was three and a half hours long.

Editors usually create a first assembly by reviewing all the visual and audio material and arranging it in the best way to tell the story.

“It had an early kind of cohesion to it,” she said.

After Schlimme had to move on to edit another film, Marshall worked closely with Deogrades for about three and a half months to put together the final cut.

Marshall said it’s normal to shoot that much footage for a 93 minute documentary.

“Because you’re in the field and you can’t predict what’s going to take place,” she said. “You need to keep rolling because anything could happen and you’re in the immediacy of it.”

Especially with a scene like the fur investigation, where a number of things could have happened.

“We could have been attacked,” she said. “There could have been an animal that we needed to focus on more than another. A scene like that you really need to just get it and then start making sense of it when you’re in the edit suite.”

With all of the film’s nominations and accolades, Marshall noted that she believes that timing is part of its success.

“People are far more open and interested in the animal issue now,” she said. “Even five years ago I don’t think it would have been funded, distributed and released with the same level of support.”

When Marshall and Beveridge went door to door pitching The Ghosts in Our Machine, the reception from funders was polarized into two competing positions.

“There was nothing ever in the middle,” she said. “It was either ‘yes we want this’ or ‘not interested’ and I think that was very characteristic of the overall general response the film gets where people either turn away or their jaws drop when they look at the poster and they can’t look away.”

Bruce Cowley, commissioning editor for the Documentary Channel at CBC, liked Marshall’s approach and her use of McArthur to frame the issue and gave her the green light to go ahead with the film. But he said he’d much rather see and fund a film that wasn’t graphic.

Marshall assured him that it wasn’t her intention to produce a film that presented the issue in vividly shocking or sensational terms.

“In all my research, I could hardly sit through most of the films I was watching on the topic,” she said. “I would feel traumatized watching those films. I wanted to make a gentle film about a very pervasively violent issue that would have a dramatic effect.”

In the end, the film fuelled a much deeper journey for Marshall into the meaning of social justice. Now she includes animal issues as part of being a compassionate activist.

“The environment, animals, humans,” she said. “It all goes together. That’s my greatest takeaway from making the film.”

Marshall also became a vegan while making the film. After the scene with Sonny and Fanny, she realized she no longer wanted to contribute to the dairy industry.

“And that was always the toughest thing,” she said. “Because I loved cheese, like many people.”