Opposition to fracking has been brewing in the Yukon for a number of years. The Yukon Party government’s recent decision to allow fracking in the Liard basin in southeast Yukon has reignited resolve in the territory to protect the lakes and rivers from fracking, a practice that was recently found to contaminate drinking water in Pennsylvania.

Members of the Liard First Nation are concerned that the Yukon Party are making deals behind closed doors with their Chief and Council which will have adverse affects on community’s drinking water and health as well as the wildlife which they rely on for food.

It is within this context that Maude Barlow and I visited Whitehorse earlier this week to express our solidarity to members of the Liard First Nation and Yukoners who have been fighting to keep fracking out of their territory.

A workshop, rally and public event

With a panoramic view of the mountains from the windows of the Mount McIntyre Recreation Centre as a backdrop, Maude Barlow and I participated in a workshop with 50 people interested in water and fracking. The Monday morning workshop was organized by CPAWS Yukon and participants included local residents, member of the Liard First Nation, the Yukon Conservation Society and Yukoners Concerned about Oil and Gas Exploration.

Barlow talked about what originally sparked her interest in water: the threat that trade agreements pose to access to drinking water, particularly the Cochabamba water waters where company Bechtel tried to even privatize the rain. She spoke about the need for human rights and environmental movements — currently on separate tracks — to collaborate and work together.

I gave an overview of the fracking fights across the country and where communities had succeeded in reclaiming power by stopping fracking including in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec and New York.

The passion with which people spoke about protecting water, communities and climate from fracking was truly inspiring. There were breakout sessions on how to support the work of the members of the Liard First Nation, energy policy, democracy and the southern lakes.

Next we went to the Yukon Legislative Assembly where a newly formed group called the Kaska Concerned About Land Protection and Good Government delivered a letter to the Yukon government to demand adequate consultation with community members. The group, made up of members of the Liard First Nation, made clear that they did not want fracking in their territory. The Kaska Nation is comprised of the Ross River Dena Council, Liard First Nation, Daylu Dena Council, Dease River First Nation and Kwadacha First Nation.

Under sunny skies, elder Alfred Chief read a moving letter outside the Legislative Assembly written by George Morgan who until last year was the Executive Director of the Liard First Nation. According to CBC, Chief said, “We remind the Premier that aboriginal rights are a collective right not held by our titular leadership.”

He added, “Fracking cannot proceed in the traditional territory of the Kaska unless there is widespread community support. We can assure you if you are planning a backroom deal with our current leadership — we have not been consulted or accommodated by them either.”

Next Kaska elder Rose Ceasar talked about her connection to the land. The Yukon News noted, “[Caesar] said she worries about the consequences of fracking on the water and the land. ‘It’s pretty dangerous. It’s pretty scary. Especially when I grew up on the land. I live off the land, I travel all over the land and you think I want to give up that right? You think I want to give that kind of future for my grandchildren. Certainly not.”

Barlow expressed her and the Council of Canadians’ solidarity with members of the Liard First Nation: “I’m here in solidarity.” She talked about the global water crisis and warned of the dangers of fracking, “The Yukon has not yet started this process. I beg you — don’t start it. The water here is so precious.”

Barlow spoke at the Beringia Centre Monday night to packed room of over 200 people. She talked about the victory of the UN recognizing the human right to water and sanitation, the water crises in Brazil, California and Detroit as well as the risks of fracking and how frack sites in Pennsylvania can be seen from space. She outlined the four principles to a water secure world: water is a public trust; water has rights too; water can teach us how to live together and water is a human right.

Fracking in the Yukon

Yukon has some of the largest shale gas reserves in the world. The reserves are found in the Liard Basin in southeastern Yukon and the Eagle Plain Basin in northern Yukon. There are coal methane reserves in the Bonnet Plume Basin and Whitehorse Trough. A temporary moratorium on shale gas development was implemented in the Whitehorse Trough in 2012.

Many First Nations have come out against fracking. The Council of Yukon First Nations, an organization of 14 First Nations, unanimously passed a resolution in July 2013 declaring traditional territories “frack-free.” Shortly after, Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation voted to ban fracking until it could be proven safe. Kaska First Nation has also come out against fracking. Even some businesses in the tourism industry are opposed to fracking.

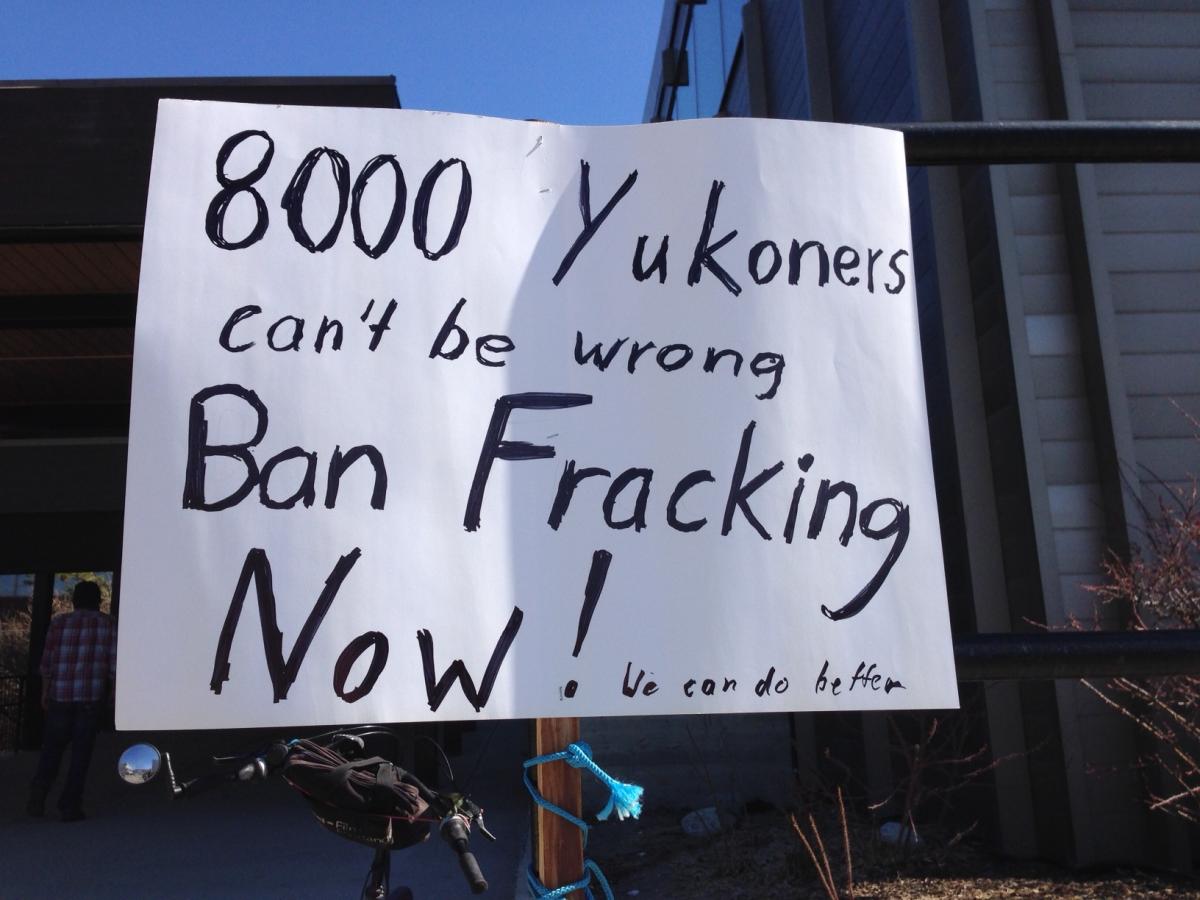

Council of Canadians Political Director Brent Patterson has noted the Council of Canadians Yukon chapter’s opposition to fracking which has called on the committee to recommend a permanent ban on fracking in the territory and organized two cross-territory tours, numerous protests, a benefit concert, written letters to the editor, gathered signatures for an anti-fracking petition. They continue to call for a ban on fracking in the territory.

The Yukon legislature created an all-party committee on hydraulic fracturing and held public consultations on the issue. The Select Committee released a report in January which made clear the committee did not come to a consensus on whether fracking could be done safely or whether fracking should be allowed in the Yukon.

The committee report outlined the risks of fracking, including surface spills, leaky well casings, fluid migration to groundwater sources, the quantity of water used, flowback water and the lack of scientific information about groundwater quality near fracking projects. The report recommended baseline testing, research of the impacts of fracking fluids on groundwater and well integrity, establishing seasonal thresholds, and mandatory disclosure of chemicals to the public.

There were 700 written submissions to the all-party select committee, 95 per cent of which were opposed to fracking. The NDP in the Yukon are opposed to fracking and the Liberal MLA, Sandy Silver, has raised concerns about fracking. Despite this opposition and the lack of consensus among committee members, on April 9, the Yukon Party government announced that it was open to shale gas projects in the Liard Basin.

Poverty in Watson Lake

Sarah Newton, a former lands director for Liard First Nation, told CBC last November that “people in Watson Lake are struggling more than ever.”

She added, “‘You can see the poverty… It’s really intense. It’s like black and white between the municipality and the villages.'”

It is not uncommon for governments to propose environmentally risky projects in low-income and poverty stricken communities. Fracking wastewater projects were proposed for low-income communities in New York.

Financial benefits of fracking unclear

The financial benefits of fracking in the Yukon are still unclear. Despite a lack of jobs in the community, the select committee report pointed out that jobs created by any fracking projects would be “fly-in, fly-out” jobs and “the majority could go to workers from outside Yukon, unless adequate training was provided for the local labour force.” The report noted that, “The Committee did not receive comprehensive information and analysis on the positive and negative economic impacts of hydraulic fractureing.” It therefore recommended that the government “conduct a thorough study of the potential economic impacts of developing a hydraulic fracturing industry.”

Gutting of environmental legislation

The Harper government has been promoting development in the North for the last several years. Council of Canadians campaigner Brigette Depape has noted, “A major threat that remains to protecting the Yukon is the Harper government, which has focused on the North for pushing resource extraction. At a speech delivered in the Yukon, Prime Minister Stephen Harper said “The North’s time has come, my friends, and you ain’t seen nothing yet” and that the nation’s future lies in the exploitation of the nation’s northern resource riches.”

The push for resource development across the country coupled with the gutting of environmental legislation leaves our lakes, rivers and groundwater unprotected. The 2012 omnibudget bills gut the Fisheries Act and removed protections from 99 per cent of the lakes and rivers in Canada under the Navigable Waters Protection Act. Changes to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act resulted in the cancellation of 3,000 environmental assessments, many of which were oil and gas projects on Indigenous lands. Many fracking projects occur on Indigenous territory.

The Yukon government recently introduced Bill 6, amendments to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment Act. CBC reported the changes would “set new timelines for environmental reviews and give more power to the government, allowing the federal Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development the ability to set binding policy for the board.”

It is very troubling that despite the clear opposition to fracking, the Yukon Party government is taking steps to open the territory up to fracking. However, community groups in the Yukon and Indigenous communities like the members of the Liard First Nation are up for the fight and many groups will stand in solidarity with them. There will also be a territorial election next year. The Yukon Party would do well to learn from the New Brunswick Conservative Party in their last election. They ignored the resounding opposition to fracking — which became a key election issue — and consequently lost power to a government who listened to the demands of communities and committed to place a moratorium on fracking.