Canada’s geothermal industry won a tremendous breakthrough in the 2017 Budget: recognition of heat (“geothermal energy”) as a renewable resource, which gives explorers access to loans as well as depreciation allowances on their tax returns. Like oil and gas companies, would-be geothermal producers will be able to issue Flow Through Shares, a staple financing mechanism in energy exploration.

Geothermal literally means “earth heat.” With modern building efficiency, geothermal equipment can pump up a few degrees difference between air and earth temperature — without any furnace or fridge system — in order to keep a building habitable in almost any weather.

Canada’s cooler climate offers a slight geothermal advantage, in that efficient buildings tend to overheat, and need cool surroundings to accept the extra heat. Milder climates like southern B.C. and Ontario are suited to replacing furnaces and air conditioning with heat pumps, waist-high heat exchangers that look like like giant mushrooms and hum along quietly outside the house.

Budget 2017 allows $182 million for retrofitting or constructing “net zero” buildings — buildings that use no more energy (electricity, heat, etc) than they produce through renewable sources such as rooftop solar panels. Now that the federal government recognizes geothermal energy as a renewable resource, geothermal buildings should qualify as “net zero” because they don’t cause any emissions.

Geothermal systems provide baseload power in a way that solar or wind systems can’t promise. While installing geothermal systems carries an upfront cost of two or three times as much as conventional HVAC systems, the trade-off is that these systems require minimum maintenance, and no fuel.

Most areas in Canada require more home heat than above ground heat pumps can provide. However, an underground geothermal system works for almost any home. A Calgary geothermal engineer told me he’d just put a geothermal system in a home in Whitehorse, Yukon.

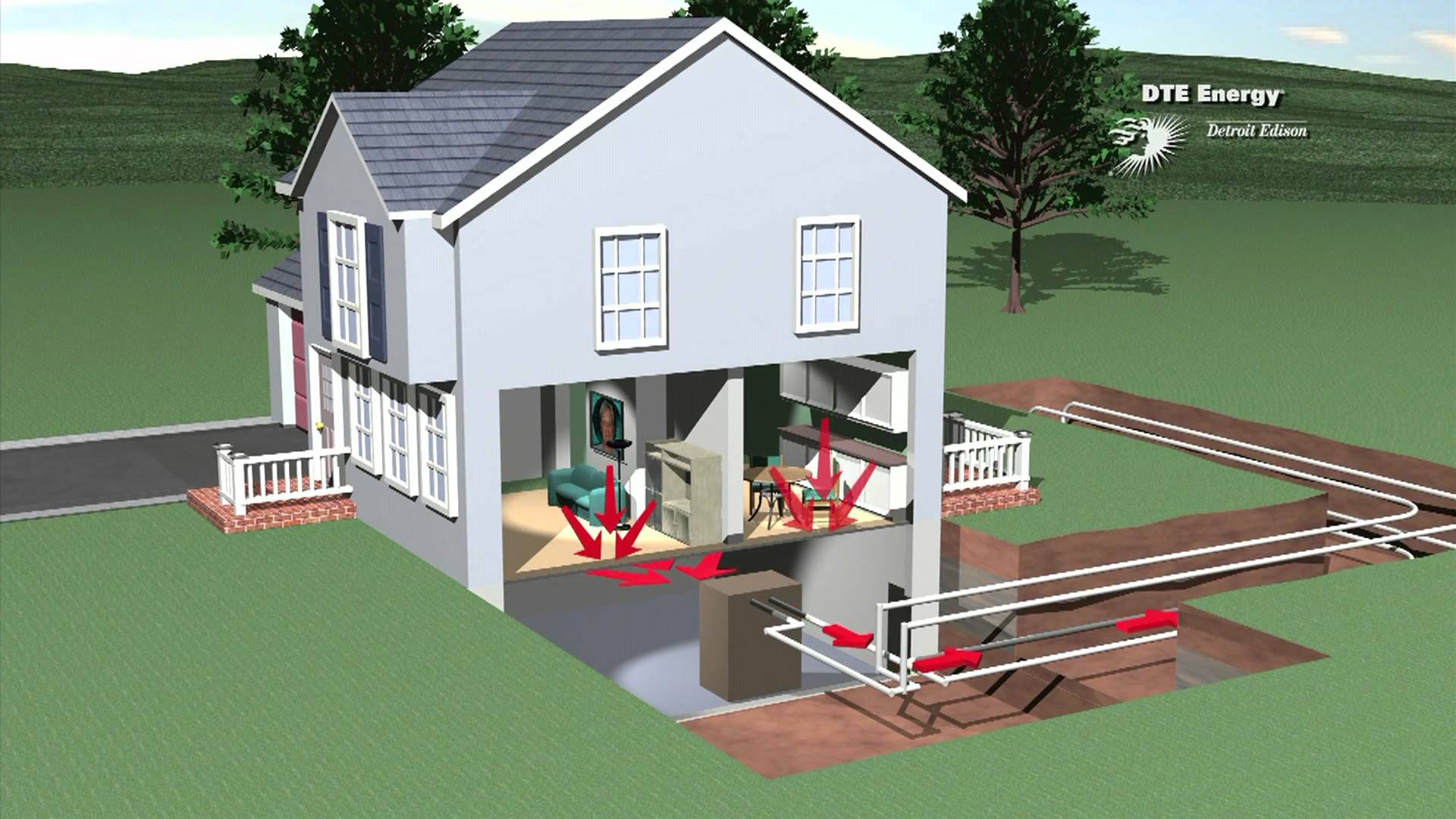

Geothermal climate control systems involve long flexible tubes that circulate water from warmer depths (maybe only two or three meters below the soil) up to the surface, where a condenser literally pumps up the temperature further. Many homeowners like to monitor their systems closely, although they rarely need to intervene.

Where geothermal HVAC systems really pay off, though, is in commercial buildings, such as Alberta’s first net-zero building, the MOSAIC Centre in Edmonton. “When you visit or work at the Mosaic Centre, you will experience a space that has been cooled or heated solely using the sun’s free radiation in combination with mother earth’s complimentary battery service,” says the MOSAIC website.

MOSAIC’s heating and cooling are courtesy of “32 geo-thermal wells (boreholes) that reach 70m (230 ft.) below the north parking lot.” Completing the system, “A ground-source heat pump, located in the mechanical room, circulates a mixture of food grade antifreeze (20 per cent propylene glycol) and water through the network of three-quarter inch vertical piping.”

Jacob Komar, MOSAIC’s lead engineer, said the extra cost for geothermal was negligible and quickly recovered through fuel savings. “The premium to go geothermal was $80,000,” he says, “which was less than one per cent of the Mosaic Centre’s $10.5-million budget… At around 50,000-60,000 ft2, commercial buildings only need a year or two to pay back the cost difference for installing a geothermal system.””

Komar called commercial buildings the “sweet spot” for geothermal — an intriguing candidate for the $200 million the federal budget allocated for developing innovative energy technologies.

Finally, the budget provides more than $600 million towards providing people in the North with secure, sustainable and renewable energy options.

Rather than solar power for communities that are in darkness several months of the year, or unpredictable wind power, the feds might consider shallow geothermal systems for Northern homes and community buildings.

Canada’s geothermal “in-place capacity” is well over a million times what Canadians actually use, Stephen Grasby, geochemist with Natural Resource Canada’s Geological Survey of Canada, told DeSmog Blog. Enough of that capacity is accessible to make a serious difference in carbon emissions.

CANgea, the Canadian Geothermal Energy Association, has created “favourability maps” of likely geothermal resources, including maps for the Northwest Territories and Yukon. Hot spots are likely to occur anywhere there are mountains, especially young mountains like the Rockies, which are still full of hot springs and caves.

Alberta’s oil fields offer special opportunities: they are well mapped, underground as well as above, and there are hundreds of thousands of “orphan” or abandoned wells across the province. Often producers abandon gas fields when they become “watered out,” wells filled with fairly warm water that could be used to power, say, greenhouses.

Under the Paris agreement, Canada has promised to cut carbon emissions by 30 per cent. Operating buildings creates about 40per cent of Canada’s carbon emissions. Including geothermal methods in retrofits and new buildings could have a big impact on reducing carbon.

Efficient geothermal energy seems to me an obvious and overdue addition to Canada’s toolbox for remedying climate change.

This blog post is based upon “Hot Treasure,” my article for the July/August 2016 Alberta Views.

Image: YouTube

Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.