The biggest Canadian star at the United Nations climate change conference in Glasgow is neither Prime Minister Trudeau nor his one-time activist environment minister.

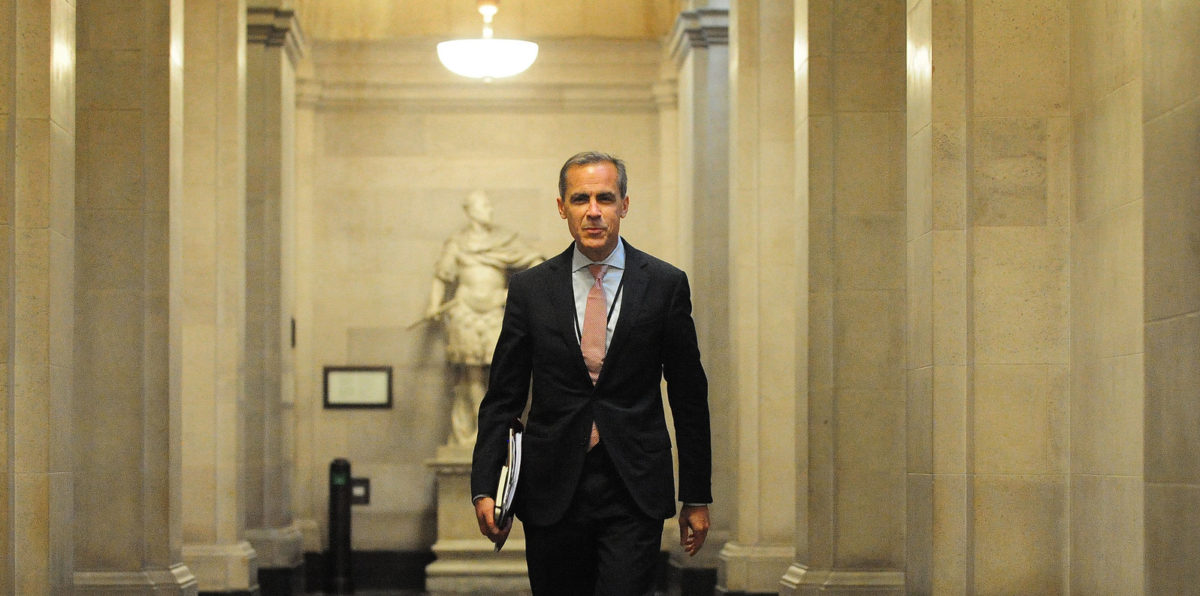

The Canadian who has made the biggest splash in Scotland is Mark Carney, former chief central banker for both Canada and the U.K.

Carney, acting as the United Nations’ special envoy for climate change and finance, claims he has convinced financial companies from around the world, worth a collective 130 trillion dollars, to commit to net zero emissions for all of their investments and loans by the year 2050.

Carney calls this group of mega-corporations the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero.

If their commitment were genuine, it could mean billions invested in clean forms of energy, innovation and non-polluting industries – with a commensurate de-investment in fossil fuels and dirty industries.

That is a big if, however.

Carney sometimes says these corporate Leviathans have no choice but to make a huge green shift. Failure to do so, he argues, would mean consigning themselves to irrelevance, and, worse, obsolescence.

But then, when challenged on the lack of oversight and accountability mechanisms in the Alliance agreement, Carney defends the corporations by saying exactly the opposite. He argues the mega-corporations do have a choice.

A great many companies refused to join his Alliance, Carney points out. And so, we should be grateful to those that did – and not make unrealistic demands of them. After all, they could change their minds.

Richest one per cent’s emissions continue to grow

It is hard to tell whether Mark Carney’s contribution is a bold and brilliant way of bringing the power of big money onboard the war on global warming, or whether it is, as youth activist Greta Thunberg describes it, an exercise in greenwashing.

What is certain, as a new report from the international development charity Oxfam demonstrates, is that the global super wealthy club – of which the participants in Carney’s alliance are charter members – is responsible for a huge and growing portion of the world’s climate-changing emissions.

During the first week of the Glasgow meeting, Oxfam released a report called Carbon Inequality in 2030, which shows the extent to which the growth of carbon emissions has been and will continue to be driven by the richest portion of the world’s population.

Oxfam worked with two highly respected European environmental research institutes on this new report. The researchers conclude that by 2030 the richest one per cent of the global population is set to have per person “emissions footprints” 25 per cent higher than they were in 1990. (The original United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was adopted in 1992.)

In addition, by 2030 the richest one per cent’s emissions will be “30 times higher” than the per person level necessary to reach the U.N. goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

By contrast, the emissions footprints of the poorest half of the entire world’s people – over 3.9 billion people – are “set to remain well below the 1.5-degrees-compatible level.”

“Carbon inequality is extreme, both globally and within most countries. If the 1.5-degree goal is to be kept alive, then carbon emissions must be cut far faster than currently

proposed,” Oxfam tells us.

But there is a key social and economic challenge to curtailing global warming which we tend to ignore.

Cutting emissions “must go hand-in-hand with measures to cut pervasive inequality and ensure that the world’s richest citizens – wherever they live – lead the way.”

Oxfam’s point about equality both globally and within most countries is a crucial one. The report explains how, as previously less developed countries grow richer and expand their wealthy classes, their per capita carbon emissions will grow.

“We estimate that by 2030, citizens of China will contribute a bigger share of the emissions of the richest 1% than citizens of the U.S., and citizens of India will contribute a bigger share than citizens of the European Union. It is also notable that the share of emissions from other countries is set to increase substantially by 2030, with major contributions coming from citizens of countries such as Saudi Arabia and Brazil.”

The key fact here is that in all of the major-emitting countries much of the blame for failing to cut emissions to the level needed to reach the 1.5 degrees goal lies with the richest one per cent.

“While carbon inequality is often most stark at the global level, inequalities within countries are also very significant,” Oxfam tells us.

“They increasingly drive the extent of global inequality, and likely have a greater impact on the political and social acceptability of national emissions reduction efforts. It is therefore notable that in all of the major emitting countries, the richest 10 per cent and one per cent nationally are set to have per capita consumption footprints substantially above the 1.5 degrees per capita level.”

Use power of government to cancel extreme wealth

None of this is meant to let the current wealthiest countries off the hook. Oxfam enunciates the concept of what should be rich countries’ “fair share” of the worldwide effort to deal with climate change.

High income countries, mostly in North America and Europe, have profited from “centuries of carbon-intensive growth.” Today, Oxfam says, those countries have the greatest economic capacity to act.

For high income countries, doing their fair share would not only mean cutting emissions to the 1.5-degrees-compatible level. It would also entail providing “adequate, new and additional international climate finance to support low- and middle-income countries who require it to limit their emissions to the same level.”

As well, there is the huge issue of the disproportionate impact of climate change on poorer countries.

Part of wealthy countries’ fair share, Oxfam insists, should include adequately financing “climate adaptation and measures to address climate-related loss and damage [in less-developed countries].”

The report then blasts rich countries for failing to even come close to their previous commitments to assume their fair share.

“The fact that these countries are still not on track to reach the 1.5 degrees per capita level by 2030, and have still not delivered the minimal commitment to mobilize $100 billion per year in international climate finance by 2020, is a double indictment of their moral and legal failure in view of the equity principle at the heart of both the U.N. Climate Change Convention and the Paris Agreement of 2015.”

To make matters worse – and Carney and his financial alliance should consider this point carefully – “the emissions of the world’s richest people linked to their capital investments are likely even greater than those associated with their direct consumption.”

Rather than merely hoping voluntary action on the part of big finance will do the trick, Oxfam recommends that “coordinated and substantial taxation of wealth is urgently required to reduce inequality and at the same time curb the emissions of the richest.”

No head of government or corporate leader has yet to make that proposal at Glasgow.

Indeed, if Carney seems reluctant to say much about increasing taxes and regulations, maybe that is because, in addition to his United Nations role, Carney is also a senior executive of the über-rich, Canadian-based asset management firm Brookfield.

Brookfield has operations in 30 countries on five continents, more than 150,000 employees, and more than $650 billion assets under management. Among its lucrative holdings are corporations that provide the most basic service of all, drinking water, to millions of Brazilians.

In case you were wondering to whom Mark Carney really reports, it is definitely not the United Nations.

Neither Carney nor anyone else associated with his Glasgow Financial Alliance ever utter a word about limiting their own profits, let alone cutting their net worth. Indeed, it is hard to imagine we can count on such a private sector elite group to confront a crisis for which it is to such a great degree responsible.

We should not expect a privileged few to act against their own economic self-interest. The Oxfam report shows us that the only viable solution to the climate crisis is for humanity, through its governments, to act collectively.

Oxfam puts it quite succinctly:

“It is time to use regulation and taxation to end extreme wealth altogether, to protect people and the planet.”