“A lie can be halfway around the world before the truth has its boots on.”

– Donald Rumsfeld

Having never been classically trained in feminism I was painfully unaware of many feminist hall-of-famers until recently. In fact, I remembered this embarrassing detail a few days ago: I didn’t know who Gloria Steinem was until she showed up in an episode of The L Word. So, needless to say, it was only a few years ago that I first heard someone say Andrea Dworkin’s name.

Initially, all I noted was that mention of her name invoked dramatic reactions — mainly of the negative persuasion. A couple months ago during a small feminist gathering I attended someone declared something to the effect of “the world would be a better place had she not been born.”

With these kinds of reactions from the feminist community itself it may not be surprising that none of Dworkin’s 11 published non-fiction books made the recent Ms. Magazine list of top 100 feminist non-fiction books of all time. It would be hard to argue that Dworkin was simply unknown to the magazine or its readers considering Ms. Magazine founder, and a peer of Dworkin’s, Gloria Steinem has said of her: “She is, I always thought, our Old Testament prophet raging in the hills, telling the truth.” Considering her prominence (regardless of how one feels of her specific politics) in the movement — it is a striking omission.

So why the hate-on? When I was trying to figure this out it seemed like the big ones were that Dworkin was credited was saying things like “all sex with men is rape” and “all men are rapists.” Unbeknownst to me, most of the people who repeated these phrases had not actually read any of her work or speeches. Neither had I.

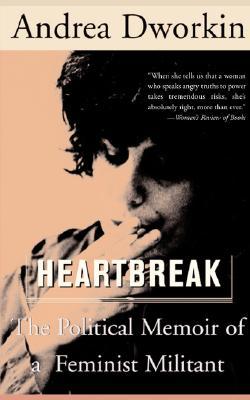

When I found out she had a memoir I thought it the perfect opportunity to take a closer look. The first thing that struck me about Heartbreak was its readability. It has some welcoming wide margins and double spacing. The second thing was that it reminded of Assata Shakur’s memoir. Which maybe seems like a strange comparison. A year apart in age both activists were in New York City during the same time period of civil rights and anti-war movements. Dworkin, throughout much of her life had very little money but she reported to have routinely donated to the Black Panther youth and literacy programs (programs Assasta Shakur was heavily involved with). Both were avid readers and self educators — critical of the huge gaps in the public education system. Dworkin read all the works of Darwin and most of Marx and Freud before she finished high school. Most striking for me was a similar sensation in their writing — the two books felt more like a two-way conversation than a telling. Both asked many questions of the reader and I often felt like I was talking with them.

“I have been asked, politely and not so politely, why I am myself. This is an accounting any woman will be called on to give if she asserts her will.” – Andrea Dworkin

Heartbreak isn’t a political manifesto. If you’re interested in dissecting her analysis this isn’t the place to turn. It is the place to turn to give one a fuller picture of the woman most feared and ridiculed in the feminist movement.

My top 4 moments in the book:

– In Grade 6 she refused to sing Silent Night with her class because she decided she liked the idea of the separation of church and state. This was also when she learned to be critical of the way adults manipulate and lie to children: “I recognized that there were a lot of ways of lying, and pretending that Christmas and Easter were secular holidays was a big lie, not a small one.”

– She took writing very seriously and spent years on her poetry. She obviously thought constantly about how to best articulate stories and arguments. She writes, “Can one write for the disposed, the marginalized, the tortured? Is there a kind of genius that can make a story as real as a tree or an idea as inevitable as taking the next breath?”

– In 1992 eco-feminist Petra Kelly was shot and killed by her partner (who then killed himself). Dworkin attended the memorial with many other activists and was disgusted by the speakers who almost exclusively spoke of her partner’s devotion to pacifism and only mentioned Kelly in passing. “I couldn’t believe nothing had changed — peace, peace, peace, love, love, love; they did not understand nor would they even consider that a man murdered a woman.” This, of course, would not be the first or last time that a feminist was awe-struck by misogyny within the progressive left.

– There are many more instances in the book when her perception of a moment of injustice feels spot on. Near the end of the book she has this one: “A few nights ago I heard the husband of a close friend on television discussing anti-rape policies that he opposes at the university. He said that he was willing to concede that rape did take place. How white of you, I thought bitterly, and then I realized that his statement was a definition of ‘white’ in motion — not even ‘white male’ but white in a country built on white ownership of blacks and white genocide of reds and white-indentured servitude of Asians and women, including white women, and brown migrant labour. He thought maybe 3 percent of women in the United States had been raped, whereas the best research shows a quarter to a third. The male interviewer agreed with the percentage pulled out of thin air: It sounded right to both of them, and neither of them felt required to fund a study or read the already existing research material. Their authority was behind their number, and in the United States authority is white.”

Charges of being divisive to “the movement” have historically been used to silence women of colour, lesbians, queers, trans, and disability justice activists. Not to mention women in general within the progressive left. This is something that’s going on now in parts of the Occupy movement. I’m not going to say that you’re splintering the movement by reading up on Dworkin and critiquing her analysis. But, if you do find yourself hating her and wishing she’d never been born I suggest that you read this book. She was radical, and critique is important, but blanket hatred unnecessarily nullifies her valuable contributions.

The only other Andrea Dworkin I have read is her 1983 speech, “I want a Twenty-Four-Hour Truce During Which There Is No Rape.” This challenging and fiery speech was delivered to a room full of 500 men. If nothing else, the woman deserves our respect. And, maybe the boots of truth will have a chance to catch up.