It is the 30th anniversary of the Montreal Massacre. The misogyny that is the background in most mass killings was in the foreground in Montreal that terrible day, December 6, 1989. After dividing the men from the women in an engineering school classroom at L’École Polytechnique, he slaughtered the women, saying: “You’re all a bunch of feminists and I hate feminists.”

Even though the killer told us why he was killing women, most of the media, especially in Quebec, at first refused to accept the explanation of feminists that this was an extreme example of the male violence women face every day.

In this excerpt from her 2018 memoir Heroes in My Head, author Judy Rebick remembers the massacre and its aftermath:

I functioned by compartmentalizing. In therapy, I was willing to explore my hidden mind, but in my life I was still avoiding the memories. So much so, that as an active feminist for more than a decade, I had never gotten involved in issues that addressed violence against women; I hadn’t even attended the Take Back the Night marches. Subconsciously, I feared they would bring up my own history of abuse.

All that changed on December 6, 1989. It is a day I will never forget. I was driving home from work when I heard the news on the radio: a gunman was shooting students at the École Polytechnique, an engineering school affiliated with the Université de Montréal. I slowed down and turned up the volume. Who was he killing? How many? Why?

I parked my car in front of my apartment and listened to the radio. Then I heard it: the man had separated the men from the women then shot 28 students, killing 14 women. While he was on his rampage, he said, “You’re all a bunch of feminists and I hate feminists.”

I could hardly breathe. A man had targeted the female students at a school where the vast majority were male. He killed them because he believed that feminists had ruined his life. He killed them because they were training for a man’s job. He killed them because they were women.

I felt sick. I ran up to my apartment. The minute I got in I turned on the radio and the TV. I started feeling cold, really cold. I looked at the thermostat; it was at 21 degrees. The apartment wasn’t cold. I was cold. A deep sorrow started to build in my belly. It grew and spread until I started to cry; the cry became a sob and the sob became a scream. I ran into the bedroom to get a pillow to stifle my screams.

Violence against women was epidemic but it wasn’t until December 6, 1989, that the veil covering misogyny was lifted through this act of fury and hatred. The media were saying this was the act of a madman but most feminists recognized that rage. We had been talking about it for decades. We knew that it was an extreme act of misogyny we had spent our lives fighting. It was a profound public moment that had a deep impact on anyone who had ever experienced male violence.

I was only just beginning to understand how my father’s rage and abuse had affected my life. The depth of grief I felt at the massacre was also personal grief. My father had not taken my life, but he had taken my innocence, my ability to love and be loved. He had taken my memory, my history. Up until that moment, my wounds were private. I had never consciously connected them to my politics. But now I was starting to make that link.

I called a friend to find out if there was a vigil or a rally. I needed to be with other women. A spontaneous memorial was planned for the next day. When I arrived at the location I saw about a hundred women bundled up in winter coats, quietly talking in front of the Crucified Woman statue at the University of Toronto’s Emmanuel College. It was late afternoon on a cold grey day. I hardly knew anyone. The first person I saw was Marilou McPhedran, a feminist lawyer whom I had debated recently on constitutional issues. Her usual confidence and energy was gone. It seemed as if the muscles in her face had collapsed. She was grief-stricken. I put my arms around her, not knowing what else to do. Neither one of us had ever cried in public. We came from the generation that believed tears showed weakness and we were strong women.

We didn’t have a megaphone or a mic, so we gathered in circles around the Crucified Woman. There were a few men there, but it was the women I remember, their heads down, eyes lowered, soaked in sadness, still in shock. Some women were crying. Then someone began singing a Holly Near song: “We are gentle angry women, and we are singing, singing for our lives.” We were grieving together as women, as feminists, as mothers, as sisters.

I’m pretty sure Mary Lou said a few words, or someone did, but mostly we talked about what had happened and what we were feeling. There were media asking questions and we answered in subdued voices, eyes downcast.

The week after the December 6 massacre, I was invited to speak at a rally on abortion rights in Montreal. Initially, the rally was to focus on Chantal Daigle, whose right to abortion case was going to the Supreme Court. But since it was only a week after the Montreal Massacre, it became a huge feminist memorial. Every well-known Quebec feminist — in the arts, the unions, politics, and the women’s movement — was there. When I walked into the huge auditorium at the Métropolis de Montréal on Saint Denis Street, I was overwhelmed by the size of the crowd.

The women’s movement in Quebec had been remarkably successful. They came from a highly patriarchal culture where women didn’t even have the right to vote until 1940, 20 years after the rest of the country. The women in that room had fought for and won the same degree of equality as elsewhere in Canada in much less time. In one generation they went from the highest birth rate and the highest rate of weddings to the lowest. Women’s status in society changed in a truly revolutionary way. Many feminists believed that the action of the assassin was part of a backlash against those dramatic changes.

However stunned we were in Toronto, it was much worse in Montreal. The hall was full, but it was quiet. In the bathroom, I ran into Françoise, She was a tough left-wing feminist who was never afraid to take a stand and speak her mind.

“He hated feminists.” She was slumped over the sink trying to stop crying. “He hated us but he killed these young women. How do I deal with that?”

I nodded sympathetically.

“I feel guilty,” she continued. “I know I shouldn’t but I do.”

“I understand, Françoise, but it isn’t your fault they died. It’s his fault.”

“Yes, but one of the young women even said, ‘We are not feminist.’ Imagine! They blamed us, too.”

“No, they didn’t. She was just trying to save herself and the others.”

That she felt guilty surprised me at first. But I found guilt in many of the women I talked to. He wanted to kill them, prominent feminists, but he couldn’t get to them so he killed these innocent young women instead. Was it survivor guilt? No, it was another form of oppression. Blaming the victim is a component of oppression. It’s part of patriarchy and sexism and it is part of colonialism and racism. What young women today call “rape culture” is full of this kind of shaming and blaming.

Radical feminists think all acts of violence against women are political. Violence against women exists to stop women from fighting back, from achieving equality both at a personal and at a societal level. There’s little question that the École Polytechnique killer’s act was political, just as there is little question that it was also personal, coming out of a rage against women taking his place in society. With the exception of a few prominent feminists, at the time no one in Quebec was willing to accept this explanation.

The events of December 6 reverberated through my body, my mind, and my memory. The pain of the original trauma of my father’s abuse and anger, and of all the male violence I had shut out of my mind for years and years, flooded my consciousness. Today we call it a trigger, but back then I didn’t really understand what was happening to me.

Excerpted from Heroes in My Head copyright © 2018 by Judy Rebick. Reproduced by permission of House of Anansi Press Inc., Toronto. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without written permission from the publisher. www.houseofanansi.com

Judy Rebick is the founding publisher of rabble.ca. Her latest book is a memoir Heroes in My Head.

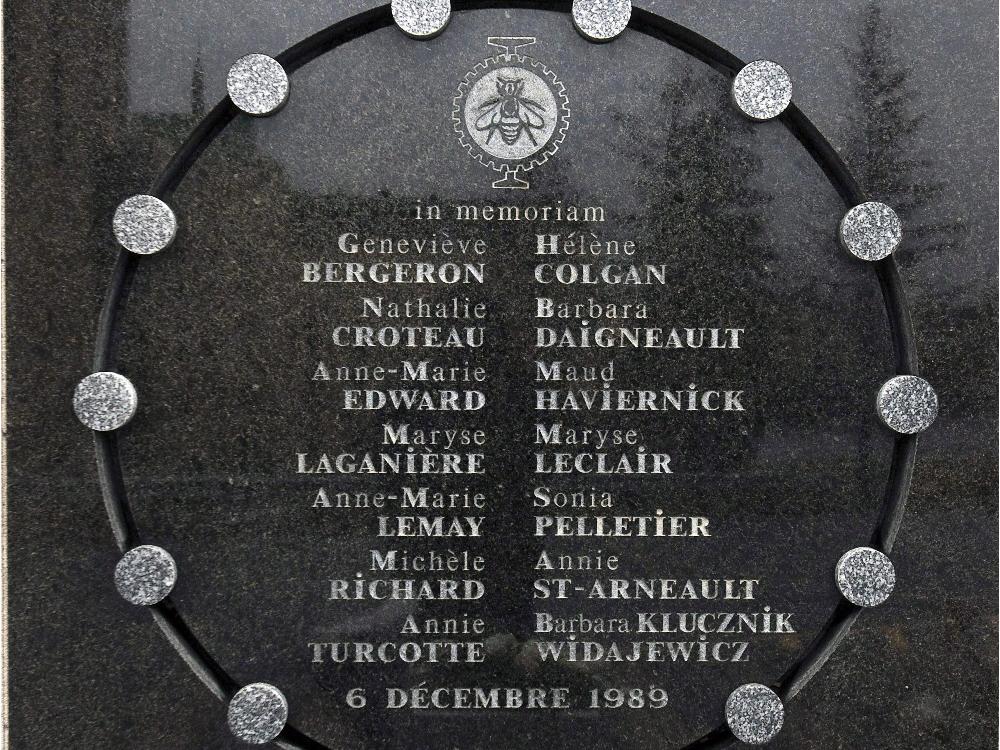

Image: L’École Polytechnique