A new report by the Canadian Medical Association provides a timely reminder that money buys better health, even in a country with a universal public health-care system. A poll commissioned by the CMA found a large and increasing gap between the health status of Canadians in lower income groups (household income less than $30,000) and their wealthier counterparts (household income over $60,000).

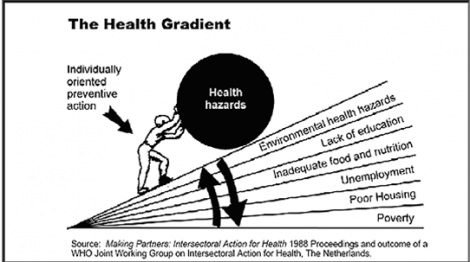

The fact that income affects health is hardly a surprise. A large body of research has shown that both globally and in Canada, income (and socioeconomic status more broadly) is closely related to virtually all health outcomes that one can think of, from life expectancy to mental health. Health experts have coined the term “social determinants of health” to draw attention to the factors outside the health-care system that affect health, and income is identified as one of the key social determinants of health.

And yet, despite all the research advances that we’ve made in understanding health and what makes people healthy, so much of the discussion is still focused on individual responsibility and lifestyle choices.

In my 10-minute conversation about the CMA report with Bill Good on his CKNW show Monday morning, the questions of poor people smoking and eating fast food came up more than once. But aren’t the poor bringing this ill health on themselves through their own “wrong” lifestyle choices, both Bill Good and a caller asked?

It’s easy to blame the poor for their misfortune and it gets us “off the hook.” If the poor make bad choices, then we don’t have to feel bad for them getting sick or do anything about the large health disparities that exist in our country. It’s just not our problem that they have double the rates of diabetes and heart disease and tend to die younger than us, wealthier Canadians.

But in reality, lifestyle choices are a relatively small factor in shaping health outcomes, much less important than our living and working conditions. In fact, living and working conditions often constrain our choices to a very large extent. The health research is very clear (p. ix):

“Chronic disease can no longer be explained only as an outcome based on engaging in the ‘wrong’ health behaviours. There is a need to look beyond individual responsibility to understand the ways in which the social environment shapes the decisions we make and the behaviours we engage in.”

In other words, the income-related health inequalities the CMA report documents represent unfair and avoidable ill health, and it causes enormous human suffering, costs years of the life of our fellow citizens. As one of the Canadian members of the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Monique Bégin points out:

The truth is that Canada — the ninth richest country in the world — is so wealthy that it manages to mask the reality of poverty, social exclusion and discrimination, the erosion of employment quality, its adverse mental health outcomes, and youth suicides. While one of the world’s biggest spenders in health care, we have one of the worst records in providing an effective social safety net. What good does it do to treat people’s illnesses, to then send them back to the conditions that made them sick?

This is a national embarrassment and we all have a responsibility to ensure that every Canadian has the opportunity to lead a healthy life.

The large body of recent health research shows that if we want to improve health among lower-income Canadians, then poverty reduction should become our No. 1 health priority. Solutions focused on individual lifestyle choices and “healthy living” are not only incredibly patronizing to lower-income Canadians, they are also bound to be ineffective.

If you’re concerned that poverty reduction is expensive, consider how much we already spend to treat preventable and avoidable income-related illness today. In a recent CCPA report, I estimate the extra costs of providing health services to the poorest 20 per cent to be $1.2 billion in B.C. alone and $9.1 billion in Canada, or 6.7 per cent of the total costs of our health-care system.

As Andre Picard concludes in an old Globe and Mail article:

The most powerful drug we have — money — is pretty plentiful in Canada. But it is not being prescribed to everyone who would benefit.

This article was first posted on the Progressive Economics Forum.