Where to begin? New York City seems impossible to encapsulate in words. But that doesn’t mean one shouldn’t try. Here goes. It is home to an arduously formed working class. Most inhabitants arrived on the southern extremity of the island and impossibly condensed into hovels and rudimentary buildings. To the elation of the ruling class, the immigrants were hopeful and ready to work. So it grew — the Broadway milieu, the Madison Avenue affectation, the charming thoroughfares around Bleecker and Chalmers Streets, skyscrapers to the heavens, provincial ‘villages’ and areas like Harlem and Williamsburg with rich traditions that are now coveted by speculating shake-down artists and chic revivalists. The skyline is breath catching and cosmopolitanism is in super-abundance. If you are looking for it, New York City is covertly bisected, the capital city of capitalism itself and yet the bearer of a radical and democratic tradition. It also the home of New York Yankees, who epitomize many of the contradictory features evoked above.

Baseball has its set of admirers. Political writer George Will, in one of his books about baseball, makes the macro point about sports in general: the Greeks, George Will tells us, considered sports as ‘morally serious because mankind’s noblest aim is the loving contemplation of worthy things, such as beauty and courage. By witnessing physical grace, the soul comes to understand and love beauty.’ (1990, p. 2) Will turned to baseball writing after his meal ticket as megaphone for Nancy and Ronald Reagan had expired with Reagan’s term limit. John Updike does Will one better on sports analogies: “For me, [Ted] Williams is the classic ballplayer of the game on a hot August weekday before a small crowd, when the only thing at stake is the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill.” (1960) I would, if given the liberty, substitute Derek Jeter for Ted Williams in Updike’s formulation, but there is no use splitting hairs. I think Updike evokes the proletarian mores of baseball, the small enjoyment of something so inconsequential and fleeting.

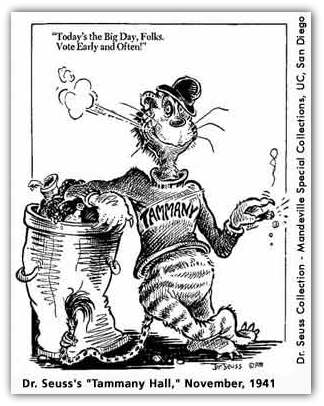

Back to New York, then. Wall street has been, of course, ever present. Tammany Hall, the original political machine, had been an organized and brute social force in New York since the American Revolution. It dominated the city until Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the Governorship in the 1930s and overhauled the old institutions of corruption, quid pro quo, and grafting with the New Deal. But the Yankees franchise sits at a chokepoint in the economy, between network television corporations, high-flying moneymen, fashion and retail sales, gentrification, the criminal underworld, real estate developers, hearty-handshakes, and the soliciting of public works projects to private businesses for political support. An ineluctable corporate utopia it would be, if it weren’t for the unpredictable reformers, of whom many would not take the surreptitious use of public office and money uncomplainingly. A history of the Yankees is a history of modernity and U.S. capitalism, and this piece will attempt to sketch that history.

Tammany Hall and the birth of the Yankees

For a considerable period, Tammany Hall, the shorthand name of New York’ political machine of epic proportions, manufactured the votes they needed with pitiless efficiency. In unsophisticated and inelegant ways, Tammany Hall’s goons would use brute coercion and arm-twisting to make the ballot boxes conform to preordained outcomes. They upended boxes and tore up the opposition’s votes. They would impersonate voters who they confronted and sent home. Their gangsters chased away the overseers and volunteers. Organized crime would guarantee a portion of the vote for a price. The machine itself was running full tilt between 1868 and 1871, when the number of votes cast were in excess of the registered voters by 8 per cent. At the apex of the Democratic machine sat Boss Twead, former mayor and corruption kingpin of Tammany Hall. Once Twead fell from power, he was hauled in front of a public inquiry. His testimony in 1877 to the New York Board of Aldermen let the daylight in on the political underworld where the counters determined the elections, not the ballots:

“Well, each ward had a representative man, who would control matters in his own ward, and whom the various members of the general committee were to look up to for advice how to control the elections.”

Tammany was chiefly organized around railway capital and monopoly landowners. When Twead was put in the dock for stealing alderman funds to pay out the election-fixing industry at the onset of the 1900s, landowners and the investment houses were forming coalitions. Tammany was cracking with Twead’s prosecution. The material basis for the Yankees was forming, as urban politics was entering a protracted period of alteration both socially and politically.

New York City as we know it was incorporated in 1898. It brought together the five boroughs – Queens, Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island. Brooklyn was the fourth largest city in the nation and Manhattan was first and their amalgamation was the key objective of the municipal restructuring. The others were added as rump boroughs but with important future roles for the Yankees.

New York City as we know it was incorporated in 1898. It brought together the five boroughs – Queens, Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island. Brooklyn was the fourth largest city in the nation and Manhattan was first and their amalgamation was the key objective of the municipal restructuring. The others were added as rump boroughs but with important future roles for the Yankees.

Brooklyn had a baseball team, the Brooklyn Dodgers. They were owned by Andrew Freedman, a consigliore of Tammany boss, Richard Croker. Between the two, they guided city contracts to associated firms in exchange for political support and ready cash. The ensuing corruption investigation would bolster the reform spirit mobilized by Twead’s downfall.

At the time, competition under monopoly conditions was rampant. In 1902, the National League’s dominance was being contested by the American League. In New York, the Giants and the Dodgers in Brooklyn as franchises were battling for fans and ticket sales, both were part of the National League. But the Yankees ownership saw the American League as the business league. Neil J. Sullivan explains the monopolizing spirit of the times:

“The American and National League owners had complicated another’s commercial lives to the point of distraction. Rival franchises in the same markets were vying for the top players in the game, and honest competition for players has always been a condition that baseball owners have hated like the capital gains tax. Lawsuits over alleged contract breaches, battles for stadium sites, and franchise shifts to new markets created additional incentives to find some kind of peace between the two leagues” (2008, p. 15)

This duopoly of leagues was contemporaneous with the centralization of the minor leagues itself, brought under the umbrage of the ‘farm system.’ Baseball and monopoly capitalism, insofar as the two are distinguishable at all, were enlivened by each other. Because professional teams call up minor leaguers at whim, the single promotion of a player could irretrievably derail a minor league team’s attendance and revenue stream. The Yankees became the first team to syndicalise with the minor leagues –- to have a farm system internal to the franchise that develops its youth rather than deplete the ranks and cause animosity between the association of minor leagues and the American and National leagues.

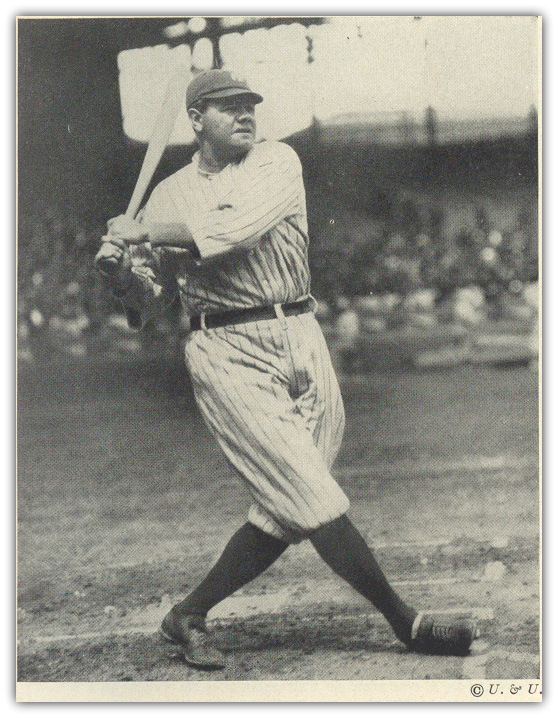

Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston became the first owners of the New York Yankees, buying the team from two Baltimore industrialists in 1902 for $460,000. Ruppert and Huston were sawmill proprietors based in Harlem. They were part of the Tammany gentry. Unsatisfied with playing third fiddle to the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers, and after seeing the opportunity to flourish following the scandal of the Chicago White Sox’ rigging the 1918 World Series, Ruppert and Huston contrived to acquire Babe Ruth from Boston’s impresario owner, Harry Frazee. Frazee was trying to shore up cash to salvage his theatrical endeavours, for which the Red Sox were a mere appendage.

Post-war euphoria had descended upon New York. Only 11 short days after the Babe Ruth deal did the totalitarian boredom of prohibition try to spoil the party. Sexuality was a bit more liberated and the volume was indeed turned up in the club-land atmosphere of New York with Babe Ruth’s party hopping and flashy cars and rancontour grandstanding.

To say Babe Ruth built Yankee Stadium is be complicit in an exaggeration. Ruppert and Huston had it built in 286 days across the Harlem River in South Bronx. The Bronx was ripe for developers with the completion of the New York City subway, a subterranean fretwork of rails used to transport the working class on those oppressively cold winter days. They coaxingly procured the land through a Tammany Hall connection. Yankee Stadium was built in 1923. Opening day ceremonies on April 23 was nothing less than a full-blown military fanfaronade, a tribute to the veterans of the Great War. The early 1920s were the formative periods of many American myths: a land of opportunity, social mobility, and individual enterprise. The Yankee franchise had built the first stadium facilitating the mass consumption of baseball. It revolutionized the sports industry.

But Babe Ruth’s role in the industrialization of baseball shouldn’t be understated. The home run was what drew the masses that Yankee stadium would house. He hit more home runs than entire teams did in a single season, which drew 1,289,000 fans in the 1920 season, 40% more than the previous year. Ruth’s popularity, however, says more about his audience than icon himself. George Will posits:

“Babe Ruth, who was as rambunctious an individualist as ever caroused across America, represented baseball’s individualist side. His specialty was baseball’s supreme act of solitary achievement, the go-it-alone blow, the home run: Do it quickly, with one swing of the bat.” (1990, p. 239)

“Babe Ruth, who was as rambunctious an individualist as ever caroused across America, represented baseball’s individualist side. His specialty was baseball’s supreme act of solitary achievement, the go-it-alone blow, the home run: Do it quickly, with one swing of the bat.” (1990, p. 239)

No doubt, Ruth epitomizes the glitz and acquisitive spirit of the 1920s. But New York at the time was undergoing monumental political changes that had important implication for the stadium industry. When Tammany boss Charles Murphy died in 1924, the machine became a fracturing, leaderless morass. Set off by the revelation of politically motivated murders, a Republican Congressman from Harlem, Fiorello LaGuardia, mobilized the underclass in the New York in favour of a vast public works campaign and a permanent end to the Tammany empire. Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the Governorship in 1928 and La Guardia won the mayoralty in 1933. Their social base in New York was the class of immigrants in New York with rising incomes prior to the Great Depression who were know fetching prices for their goods that were considered low even by the standards of the middle ages.

The New Deal and the material conditions for baseball’s expansion

The inflexibility of Herbert Hoover Republicans over public support for the depression-battered working classes combined with the discrediting of Tammany Hall was the space for President Roosevelt and La Guardia to undertaken a full-scale experimentation with the limits of Madisonian government: the budget expanded to record levels, regulatory power was enhanced, social security was introduced and collective bargaining would set wage levels among the working class as a whole. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, a human-built waterway connecting the eastern seaboard to the numberless inlet lakes and rivers in the mid-west interior, the material base for the population surge around the Great Lakes, had put faith in civil engineering and the public service. Why couldn’t this mastery of nature be extended to the social infrastructure of New York and beyond? The set of policies known as the New Deal was unified by the assumption that individual liberty needed not just protection from government encroachment but organized capitalists acting as a fetter on individual opportunity and the mobilization of the productive forces.

Roosevelt once remarked that the primary object of the New Deal was the industrialization of the U.S. South. Seeing that industry was being concentrated in the Northeast quadrant of the nation, incubated under a fortuitous tariff system, the industrialization of Dixie would militate against entrenched reserve strength of the plantation class below the Mason-Dixon line. Accessing the dormant southern proletariat and installing the public utilities needed for unadulterated economic development would, in essence, take U.S. capitalism to a new, higher plateau.

The success of the Tennessee Valley Authority in extending irrigation systems to boast the marginal productivity of Southern land undercut the Southern landowners to some extent, and allowed for the growth of cities across the Sunbelt. The power projects spread westward towards the Pacific coast and northwest all the way to California bringing a unified structure to the American economy.

The success of the Tennessee Valley Authority in extending irrigation systems to boast the marginal productivity of Southern land undercut the Southern landowners to some extent, and allowed for the growth of cities across the Sunbelt. The power projects spread westward towards the Pacific coast and northwest all the way to California bringing a unified structure to the American economy.

Until after the Axis powers were defeated in 1945, Chicago and St. Louis represented the ‘western division’ of major league baseball and Cincinnati its ‘southern flank.’ Put into perspective, roughly three quarters of the US population had no direct access to baseball except through distant news reports. The Pacific Coast league, namely Los Angeles, had yet to be assimilated into the burgeoning sports industry. Names like Mellon, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Morgan, Ford, McCormick, and Vanderbilt, from Chicago and New York, Boston and Philadelphia had dominated the U.S. mainstream political, culturally, and economically. The important changes to major league baseball wrought by the New Deal would realize new economic forces in the Sunbelt and Pacific Rim that stretch from Southern California to the Southwest and Texas into the Deep South before reaching Florida. The growth of these urban centres would spawn the franchises that dominate the Major league today.

The bombast of Babe Ruth in the 1920s would become obscured by the more humble images of Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio that seemed suitable to the hard-work ethos of the 1930s. Neil Sullivan insightfully notes their significance:

“Where Ruth’s swagger was emblematic of the Roaring Twenties, the quiet dignity of Gehrig and DiMaggio fit the Depression years. These men were the children of immigrants who personified the importance of hard work and low profile. Gehrig’s consecutive game streak was a kind of homage to people who went to work every day whether they felt like it or not. During the Depression, it might even have suggested a fear that, if you missed a day of work, you might be replaced. You could ask Wally Pipp.” (2008, p. 71-72)

The Yankees would win 8 World Series championships between 1923 and 1939 and 11 American League pennants.

At the curtain-close of World War II in early 1945, the Yankees franchise and its stadium were sold by the Ruppert estate to a trio of businessmen for $2.8 million dollars. Del Webb, Dan Topping and Larry MacPhail were the new owners for whom the dirty rudiments of influence brokering, revolving doors, and Mafioso muscle were the stock in trade. The 1950s were the formative period of stadium deals, franchise relocation and major league expansion. The owners, like Webb who were leagued in with organized crime –- he and Bugsy Seigel had joint ventures in the Las Vegas casino industry -– were given the kid-glove treatment by the government for their improprieties and criminal indiscretions. Much like Harry Frazee, the man who sold Babe Ruth to shore up theatre-money, Webb used the Yankees as a diversion from his underworld connections, a money-laundering spinoff. Whereas the 1918 White Sox were banished and humiliated for rigging the World Series and their connection to the rotten arch of Chicago mobsters, Webb and baseball owners like him eluded any similar fate. The luckless underclass, then as now, falls under a different, more pitiless rule of law.

Race-ball

Baseball was not exempt from the forces of integration in the period, something long bloody overdue. Jackie Robinson epitomized the struggle. His number, 42, was retired in 1997 across the league. Only one player currently wears it, Mariano Riviera, the sure shot hall-of-famer closer for the New York Yankees. Whereas Babe Ruth made the American League about power, flash, and money, Jackie Robinson defined the National League by speed and aggressive play.

Black America, the only involuntary immigrants in the nation, were ready to reap the refinements of the post-war boom after centuries of slavery, black codes, and interwar poverty. Baseball’s popularity had grown in exponential increments since the civil war and the infusion of black Americans bolstered the game’s allure in a variety of ways. Predictably, the competition got better. The Yankees were holdouts on integration, being one of the last teams to give black players a uniform. But the culture of baseball was changing. Players and coaches dropping ‘the N word’ in public forums like radio were instantly and widely discredited. The old lingo and code words were, gladly, growing hoarse in the public’s ear.

But while black players like Jackie Robinson may have broken the colour-line, they had no illusions about race, sports and the new America. As Robinson himself put it:

But while black players like Jackie Robinson may have broken the colour-line, they had no illusions about race, sports and the new America. As Robinson himself put it:

“As a black man, I find it quite discouraging to look around and find how little has been done to lift minorities from the depths of poverty and despair… all these guys who are saying we’ve got it made through athletics; it’s just not so. You, as an individual can make it, but I think we’ve got to concern ourselves with the masses of the people, not by what happens as an individual.”

What is more, America – and New York especially – was enduring another cataclysmic demographic upheaval, a second ‘great migration.’ Droves of black families in search of the opportunities withheld from them by the Dixie overclass congregated in Northern cities. The merciless irony is, though, that New York was hemorrhaging jobs to the U.S. South at the precise moment black families came to the boroughs in search of them.

According to Ira Rosenwaike’s Population History of New York City (1972), the black population in the Bronx doubled during the 1960s while the white population dropped by a sixth. The Brooklyn Dodgers relocated to Los Angeles as soon as the conditions proved fortuitous. Exurban towns rose to prominence due to Eisenhower’s interstate highway project, government subsidized mortgages, automobile sales, public school construction, and white flight. Areas of New York City became segregated zones of almost cartoonish racism. The abrupt decline of opportunities for the working poor were the material conditions for parts of the city, namely the Bronx, to descend into criminal anarchy.

Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris carried the day for the Yankees until the mid-1960s. Maris was canonized in 1961 for breaking Ruth’s homerun record by hitting 61 in a single season. The Yankees continued to win and win. Five World Series wins in a row (1949-1953), then four in a row (1955-1958), and then another four (1960-1964). But the sale of the media conglomerate CBS would be the apex of the Yankee dynasty, who after 1964 would become an emaciated husk of their former selves, eerily paralleling the trajectory of the post-war economy as a whole.

When CBS purchased the Yankees in August 1964, Webb and Topping reaped a $14 million dollar dividend. The team would absolutely atrophy under the ownership of the Columbia Broadcast System. This change in ownership was of cardinal importance for the future of baseball for two reasons: (1) an impersonal corporate entity would control a baseball club; (2) the game would become televised for nightly consumption and mass delectation made possible by the venerable press racket in the United States.

CBS and the Bronx Zoo

Edward Jay Epstein’s News from Nowhere (1973) investigates the ascension of the U.S. media to a proverbial fourth branch of government. Network news services — NBC, ABC, or CBS — are large organizations with hundreds of employees that feed a select amount of highly editorialized news stories at fixed times each night of the working week. At the time of CBS’s Yankees purchase, they controlled 205 of 550 affiliated local stations reaching 26 million viewers. The association of franchise owners were enthralled and approved the sale with virtual unanimity. Television had cemented itself as a permanent feature of US culture in the 1950s and televised baseball would expand the market for the sport. What owner wouldn’t want a slice of that?

During CBS’s tenure as owner of Yankees, they languished as a team and the stadium, like the Bronx itself, speedily dilapidated. CBS’s high-flying profits were not directed into rebuilding the stadium or the community, the burden of which fell on the local government. But The New Deal ethos of government was cracking up. David Harvey explains:

“The subsequent New York City fiscal crisis of 1975 was hugely important because it controlled one of the largest public budgets in the world…New York then became the centre for the invention of neoliberal practices of gifting moral hazard to the banks and making the people pay up through the restructuring of municipal contract and services.” (2012, p. 5)

Yankee Stadium’s repairs were estimated by the New York Times to be in excess of $75,000,000 and possibly in need of another $150 million to account for parking facilities and future interest payments. Mayor John Lindsay spearheaded the drive inside the local government to transfer $100 million to one of the richest and most power media conglomerations in human history. The ‘stadium that Ruth built’ was not going to be the stadium that Reggie Jackson repaired, despite the Yankees winning the World Series in 1977 and 1978. That would fall to the taxpayers whose public services were irretrievably rolled back by the unaccustomed austerity of the new economic consensus. If ever there was a demonstration of the new neoliberal protocol it is this: the rich work only when they are given money and the working class work when it is taken for them. Hundreds of millions in public tenders for fat cat owners, on the one hand, and start-from-scratch, individual initiative for the Bronx working class, on the other. Little wonder, then, that George Orwell said ‘sport is the unfailing source of ill will.’

With New York City going totally bust in 1976, a deal was confected to divest CBS of the Yankee franchise (which was never anything to them but a Frazee-type appendage to an entertainment venture) and a consortium of 12 owners, one of which was George Steinbrenner, a shipbuilding capitalist from Ohio. The hard times economy of the 1970s and 80s rendered it totally unfeasible for eastern cities to house two franchises, especially with white flight and  suburban development operating at maximum capacity. (Only the wealth of New York could sustain both the Yankees and Mets) The burgeoning cities across the U.S. heartland starting building stadiums with public money. Between 1966 and 1972, Anaheim, Arlington, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, San Diego, Washington, D.C., and even New York (Shea Stadium) joined the chorus line.

suburban development operating at maximum capacity. (Only the wealth of New York could sustain both the Yankees and Mets) The burgeoning cities across the U.S. heartland starting building stadiums with public money. Between 1966 and 1972, Anaheim, Arlington, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, San Diego, Washington, D.C., and even New York (Shea Stadium) joined the chorus line.

This period coincided with a landmark ruling concerning the reserve clause, the tort law that allowed owners to unilaterally extended a player’s contract to an indefinite period. “Free agency” was instituted, and the players could now collectively bargain for their own salary and terms of employment. Steinbrenner was the first to catch wind of the enormous bonanza that lay at the Yankees feet from the ruling. With the economy in the doldrums, baseball attendance was still expanding in the Bronx. I can only hazard two plausible explanations for this anomaly. First, the fiery antics of Billy Martin, George Steinbrenner, and Reggie Jackson (perpetually at one another’s throat), not to mention the ‘manly’ appearance of Goose Gossage, made the Yankees a gritty circus that people wouldn’t dare miss. Jackson often attributed his dramatic blowouts with manager Billy Martin to the latter’s race-based managerial decisions, and the spectacle drew in audiences during New York’s rough mid-1970s, but they also spoke to the simmering racism that still pervaded the game and, especially, the Yankees. Second, demoralized youth were dreaming of a bright shiny future as a Yankees player, luxurious dreams from the children of the New York working class who were seeing their pensions, incomes, and futures disintegrate with every pay cheque.

As such, between 1975 and 1977, ticket sales doubled from 1.2 million a year to 2.4 million filling Steinbrenner’s war chest with $10 million in additional revenue to purchase these free agents. (Sullivan, 2008: p. 157) ‘Catfish’ Hunter was the first to have his contract bought and sold in this way by the Yankees. Reggie Jackson soon followed. The Yankees would buy themselves two consecutive World Series titles, Reggie Jackson earned the moniker ‘Mr. October’ for hitting a homeruns at a whim and under the unspeakable pressure from Yankee fandom. Apart from these memorable moments in 1977 and 1978, the Yankees were in a championship drought between 1962 and 1996.

But even in these forgettable years (the Mattingly era) the Yankee franchise continued to revolutionize the business of the game. With the City footing the maintenance fees for the stadium, Steinbrenner was free to pursue lucrative television contracts, matchless in the history of sports. In 1989, the Steinbrenner inked a cable TV deal and the Yankees had an annual revenue stream of $40 million a season from the TV deal alone. TV, not the stadium, became the primary source of a club’s revenue.

Steinbrenner and the tree-shaker

Giving public moneys to private companies is usually cast in the loftiest of terms. Where its under pretense of a ‘stimulus package’ or stoking ‘wider economic activity,’ it is never shocking to realize that such transfers are quid pro quo money for political back-scratching. Between 1990 and 2001, Steinbrenner was unstoppably shaking down Mayors Dinkins and Guiliani for a new stadium under the promise of commercial returns for everyone. Andrew Zimbalist and Roger Noll (2000) set to the task of studying the effects public money for stadiums had on wider economic activity. Their results turn up against it all. Dennis Zimmerman’s study (1996) of the tax implications concludes that the people who benefit most from publicly financed stadiums don’t actually pay for them. His example is Walter O’Malley, who ostensibly paid for Dodger Stadium. He may have outlaid the money, but he only did so because ticket sales would allow him to recoup his cost and turn a hefty profit. The Dodger’s fans bought the stadium and under compulsory taxation no less. Robert Baade and Allen Sanderson (1997), not to mention James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort in their study (1997), have further concluded that the publicly financed stadiums will have negative economic effects. Money spent on sporting events is money not spent elsewhere and is gobbled up mostly by stadium operations and paying player’s salaries. On the whole, the economy will lose.

Tuesday morning. Two commandeered planes-cum-cruise missiles smashed the twin towers to atoms and eddies of metal and poison dust. Noble people rushed to unearth those who screamed below. New Yorkers resolved to solidarity, not looting. Mayor Guliani emerged as a moral leader who presence was ever felt at Yankees games as they headed into the 2001 playoffs. Derek Jeter immortalized himself with his backhanded toss from an impossible angle to the plate to save a run against the Oakland Athletics. Avoiding the sweep, the Yankees made it to game 7 of the World Series. The heavens were seemingly smiling upon them. The Yankees would lose that year to Arizona. They were denied a four-peat, having won in 1998, 1999, and 2000.

Guilani, in the throes of a deep recession and on the heels of the NASDAQ collapse, was determined to give the Yankees public money for a new stadium that Steinbrenner had been calling for since his lucrative cable deal in 1989. The Yankees had reclaimed the commanding heights of baseball and the end of the stadium that Ruth built was nigh.

Michael Lewis’ Moneyball (2003) made salient the sweeping changing to the game indirectly provoked by the money-machine in New York. In 2002, the Yankees had a payroll of $126 million, led by high-priced superstars Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez. Oakland and Tampa Bay, in stark contrast, had payrolls of $40 million.  The wasteful inequalities of capitalism were not lost on Billy Beane, the Oakland A’s owner, who contribution to the game was to apply the law of value to every part of the game. The shrewd assessments of risk and gain more suitable to the derivative department of New York’s investment houses were transposed to baseball statistics. MBAs were recruited to front offices and probed by general managers for any insight on squeezing the most out of players for the least amount of money. Sabermetric analysis replaced the bidding war for homerun hitters. Jackie Robinson-types were replacing Babe Ruth brutes. The sheer calculating spirit of capitalism had irretrievably colonized baseball as low budget franchises tried to undercut the Yankee spending colossus.

The wasteful inequalities of capitalism were not lost on Billy Beane, the Oakland A’s owner, who contribution to the game was to apply the law of value to every part of the game. The shrewd assessments of risk and gain more suitable to the derivative department of New York’s investment houses were transposed to baseball statistics. MBAs were recruited to front offices and probed by general managers for any insight on squeezing the most out of players for the least amount of money. Sabermetric analysis replaced the bidding war for homerun hitters. Jackie Robinson-types were replacing Babe Ruth brutes. The sheer calculating spirit of capitalism had irretrievably colonized baseball as low budget franchises tried to undercut the Yankee spending colossus.

Mayor Bloomberg, who opposed Guilani’s plan in 2002, signed on to build a new stadium for the Yankees in 2008, which opened a year later. It cost the city $528 million. According to “Good Jobs for New York,” a watchdog website for city spending in New York, the Yankee franchise persuaded city officials to seize 24 acres of land for the site without any public consultation. In addition to the stadium, demolition and clean-up the public had to foot an estimated $1.2 billion dollars. The land grab obliterated the public spaces like Macomb’s Dam and John Mullaly Parks, rendered as they currently are, into parking lots. The Yankees won their inaugural season at the new Yankee stadium.

These are the breaks in New York. The ancien regime of Tammany Hall still exists in an undigested form in Bloomberg’s New York. The concept of the ‘honest graft’ still echoes throughout in every stadium deal tendered with public funds. Yet the fans are still summoned despite the steadfast reduction of the wage-packet in the US since about the time of New York bankruptcy. Any elementary look at New York will reveal it to be a place where the entertainment industry is owned by high rollers. The enormous bankroll of the Yankees is as such not because they need to outbid other baseball teams, it is because they need to outbid the countless other things to do in New York City itself. All other baseball teams are really playing their game of stadium and cable deals, merchandise peddling, real estate development, and ticket sales. At the very least, and thankfully I might add, they play decent baseball.

Justin Panos is an independent journalist, student and researcher who has published in Briarpatch, Peace Magazine and writes a column for WRGMAG.com. He lives in Toronto where he can be found wandering about and can be reached at [email protected] .

………….

Andrew Zimbalist and Roger Noll (2000) “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 14, No. 3, 2000, pp. 95-114.

David Harvey (2012) “The Urban Roots of Financial Crises: Reclaiming the City for Anti-Capitalist Struggle” in Leo Panitch, Greg Albo and Vivek Chibber (Eds.) Socialist Register 2012, Toronto: Fernwood.

Dennis Zimmerman (1996) Tax-Exempt Bonds and the Economics of National Sports Stadiums Report for Congress, May 29

Edward Jay Epstein (1973) News from Nowhere: Television and the News, New York: Ivan R. Dee

George Will (1990) Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball, New York: Harper Collins Press

Ira Rosenwaike (1972) Population History of New York City, New York: Syracuse University Press

James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort (1997) Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

John Updike (1960) ‘Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu’, New Yorker, Oct 22

Michael Lewis (2003) Moneyball. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

Neil J Sullivan (2008) The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York, New York: Oxford University Press

Robert Baade and Allen Sanderson (1997) “Cities under Seige: How the Changing Financial Structure of Professional Sports is Putting Cities at Risk and What to Do about It” in Wallace Hendricks, ed., Advances in the Economics of Sports, vol.2, Connecticut: JAI Press, pp. 77-114.