One great myth of the West during the post World War II and Cold War periods — and for a number of years after the Cold War — was that democracy and capitalism were intimately connected.

Democracy, the myth went, happened where there was “free enterprise.” Capitalism was either a pre-condition to free and democratic political institutions, or an inevitable and natural corollary of them.

Well, 21st Century China has given the lie to that myth.

Of course, Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy — where, in both cases, private business flourished in totalitarian states — should have negated that Cold War myth even before it took hold.

But those dictatorships were in the past, and easy to ignore.

China is a present-day phenomenon, and impossible to ignore.

Bankers, policymakers, trade consultants and others who promote economic ties to China all recognize the strange irony of a one-party Communist dictatorship assuming the new role of capitalist powerhouse.

The take on the democracy-capitalism nexus in China that those elites have is: “It will all work out in due course.” The free market will, over time, bring free — or at least freer — political institutions to China.

One day, they say, there will be some sort democracy in China. A burgeoning middle class will demand it.

And just as China has evolved quite quickly from the status of a low value-added, cheap labour economy to a leading supplier of everything from television sets to cutting edge environmental technologies, so will it evolve politically.

What emerges may not resemble democracy as we know it in the West. But it will be something quite different from the current one-party state.

It’s a theory — but who can tell what will happen, really?

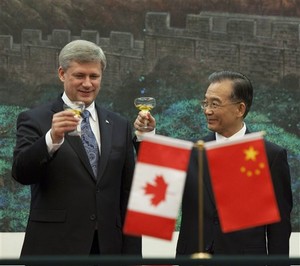

In the meantime, after a brief flirtation with a strong human rights stance vis-à-vis China, the current Conservative Government in Ottawa seems to have fallen in love with the Chinese economic leviathan.

Fostering close economic relations with China

China is a good part of the reason for which Harper and his colleagues want Canada to be part of a new Pacific free trade zone.

The Chinese market is almost the only reason for which they want that pipeline to ship tar sands bitumen from northern Alberta through some of the most environmentally fragile territory anywhere in Canada (much of it home to First Nations) to the British Columbia coast.

And the growing economic importance of China is why Canada has negotiated a two-way agreement on foreign investment with that country, almost in total secrecy and with no public discussion or debate.

The deal is known by an opaque and nearly impossible-to-remember acronym: FIPPA, the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement.

The agreement’s putative purpose is to protect Canadians who invest in China and Chinese who invest in Canada from unfair and arbitrary treatment. And there is a muscular arbitration process built into the agreement to settle disputes and grievances.

Canada has signed a number of these reciprocal investment agreements, in most cases with countries in which Canadian investment vastly outweighs those countries’ investment in Canada.

In those cases, the deals have been much to the advantage of Canadian business.

Canadian firms that do business internationally have benefitted by having formal protection against what they sometimes perceive as abusive and arbitrary actions by foreign governments.

China is a different story.

Chinese investment in Canada is far greater than Canadian investment in China.

And, in this Brave New World, where one party Communists have partially morphed into globe-trotting capitalists, some of that Chinese investment is by state-owned companies. Witness the Nexen takeover case in Alberta. China clearly wants to own a piece of Canadian energy.

In addition, we have to remember that this agreement does not concern trade. It will not give Canada greater access to the much-touted, vast and potentially lucrative Chinese market.

What many in Canada fear this reciprocal investment deal will do, however, is give Chinese investors veto power over Canadian social and environmental rules and laws.

An arbitration process that could trump Canadian laws?

In an interview on CBC radio’s The Current, Osgoode Hall law professor Gus Van Harten argued that while the investment deal has protection for Canadian health and safety legislation, it could result in attacks on many Canadian economic and environmental measures.

The agreement’s arbitration process could trump Canadian laws, both federal and provincial, and even trump Canadian Supreme Court decisions.

Van Harten cites cases involving similar agreements between China and, say, Belgium, where the agreement’s arbitrators have awarded billions of taxpayer dollars to litigating Chinese firms.

It is worth listening to the complete broadcast of that day’s The Current, because it is just about the only public debate we’ve had on this issue.

The NDP’s trade critic Don Davies tried to get the Commons Trade Committee to consider this investment deal. That would have meant public hearings with witnesses representing a variety of views and interests. The Conservatives blocked that effort.

Now, the Official Opposition is pushing for a “take note” debate in Parliament on this agreement.

Such a debate could not stop the deal from going forward, but would allow for at least some public airing of all the complex elements and potentially dangerous consequences of this investment deal.

The interests of Canadian investors are paramount

The government argues that it is going beyond the call of duty by tabling this agreement in Parliament, something the Liberals did not do with similar investment agreements.

David Fung of the Canada-China Business Council defended the agreement on The Current. His main argument seemed to be that Canadian investors welcome this deal, and that Van Harten’s warning of potentially dire consequences is “fear-mongering.”

In the House, both the Trade Minister Ed Fast and the Prime Minister hewed to the same line. And, of course, for good measure, Fast also added the Conservatives’ by now ritual jab about the NDP’s “job killing carbon tax.”

NDP Leader Tom Mulcair pointed out that this deal with China is meant to last 31 years, but that it is not customary for any government to adopt measures that bind subsequent governments.

“Let me be very clear,” Mulcair said in the House on Wednesday, “The Conservatives will not tie the hands of the NDP. We will revoke this agreement if it is not in the best interests of Canadians.”

The Prime Minister’s response might very well become a new Conservative attack line:

“The leader of the NDP is saying he would revoke the hard-earned right of Canadian investors to be protected in a marketplace like China. That is precisely why Canadian investors, the Canadian business community and the Canadian public at large does not trust the NDP with economic policy.”

The Prime Minister did not mention the “hard-earned right” of Canadian governments to legislate environmental rules. Unlike previous Conservatives, such as Brian Mulroney, Mr. Harper has not given the environment a high priority. Some might say he has not even given it a low priority.

Harper is, not surprisingly, most solicitous of Canadian investors. He has also occasionally shown some, at least notional, concern for First Nations.

Well, this agreement could actually have very significant consequences for the “Crown-First Nation” relationship in which the Prime Minister claims he places such great store.

More about that in the days to come.

Karl Nerenberg covers news for the rest of us from Parliament Hill. Donate to support his efforts today. Karl has been a journalist for over 25 years including eight years as the producer of the CBC show The House.